Energizing the next environmental leaders

Wake Forest’s environmental educators teach Winston-Salem middle schoolers about sustainability

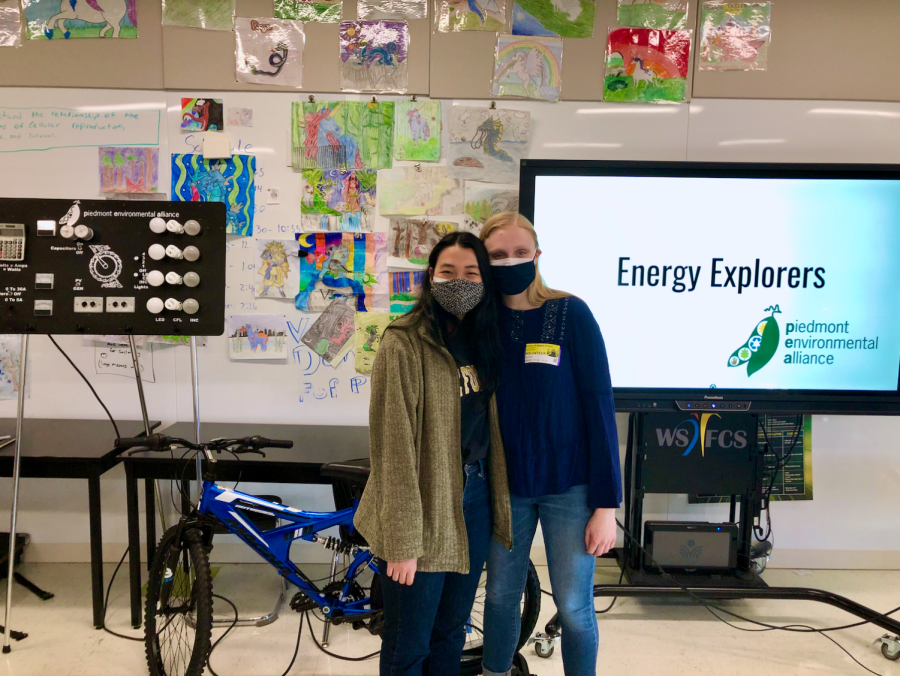

Photo courtesy of Julia McElhinny

Using Powerpoint and an energy-producing bike, senior Julia McElhinny and sophomore Emy Yamamto visit WSFCS seventh-grade classrooms to talk about sustainability

February 17, 2022

A seventh-grader huffs as he pedals the stationary energy-producing bike as fast as he can — but the incandescent bulbs hooked up to the circuit board barely flickered on.

“There’s got to be a better way to light a lightbulb,” he said, wiping sweat from his forehead. His classmates at Southeast Middle School laughed, but senior Julia McElhinny, president of the Environmental Educators group at Wake Forest, smiled slyly as she explained that there actually were more efficient ways to use energy.

The Wake Forest Environmental Educators visit local Winston-Salem middle schools on a weekly basis to give presentations about environmental issues and sustainability solutions to students. The curriculum, titled “Energy Explorers,” is put together by the Piedmont Environmental Alliance (PEA).

It includes topics such as how electricity is produced, the impact of fossil fuels on the environment, climate change and renewable energy. The curriculum even suggests small steps students could take to lower their carbon footprint, such as unplugging lights when not in use and encouraging their parents to buy LED light bulbs.

At the end of the slideshow presentation, McElhinny asks for a student volunteer to ride the “energy bike,” which is hooked up to three types of lightbulbs: incandescent, fluorescent and LED.

The energy generated by pedaling the back wheel of the bike is enough to cause the bulbs to flicker to life. The level of difficulty, however, varies for each bulb, with LEDs being the easiest to light, fluorescents being the middle ground and incandescents the hardest. The exercise is meant to demonstrate how much energy it takes to power inefficient energy consumers and encourage students to switch to more energy-efficient choices.

McElhinny has been volunteering with this group since her freshman year. Almost immediately after arriving at Wake Forest, McElhinny was struck by how isolated the campus was from the rest of Winston-Salem.

“Wake Forest students exist in a bubble — out of all the student organizations on campus, not nearly enough of them are active in the Winston-Salem community,” McElhinny said.

“That’s part of why this program is so important; it bridges the gap between civic engagement and sustainability and the rest of Winston-Salem.”

A larger part of the program’s importance is its impact on local middle school students, especially those who would not have received any sort of education on the environment without this curriculum.

“Environmental education isn’t even mentioned in North Carolina’s learning standards, which is so detrimental to not just these students’ future, but to all of us. How are we supposed to have the next generation of leaders if kids don’t even begin to discuss environmental issues until college?”McElhinny said.

The presence of educational inequity isn’t the only issue McElhinny has noticed while volunteering at Winston-Salem/Forsyth County Schools (WSFCS). Environmental inequity often affects the same communities of students who attend Title I schools in the county.

Receiving environmental education, therefore, is crucial for these students, since they are the most likely to experience the adverse effects of energy production, such as air and water pollution.

“The kids we are educating — those in Title I schools — are likely going to be the ones that are the most impacted by the environmental issues we are talking about,” McElhinny said.

During the threat of the Weaver Fertilizer Company fire the week of Jan. 31, students at North Hills Elementary School weren’t able to go to school from Tuesday to Thursday, due to the building being within the designated one-mile evacuation zone. To McElhinny, this was a poignant example of why the “Energy Explorers” curriculum is especially important for underprivileged students.

“While it wasn’t a climate-related event, the Weaver fire had disproportionate impacts on families of color,” McElhinny said. “This event mirrored a pattern that we have seen so many times with things like hurricanes and wildfires — and only expect to continue to see in the future that will affect these communities.”

Not everybody agrees with teaching social inequity concepts, however. In the summer of 2020, WSFCS school district struck down McElhinny’s request to add a brief explanation of environmental racism to the presentation. In response, she has tried to approach the issue in more roundabout ways, such as talking about how certain communities, like those in Flint, MI, are often more directly affected by lead-contaminated water than others.

McElhinny acknowledged that although she believes these environmental issues are critical, not all students will be receptive to the curriculum right away.

“It’s really important to be understanding of the fact that some schools just don’t offer field trips to outdoor places, or have gardens, or teach their kids about nature,” McElhinny said. “Some kids might be thinking, my family is struggling financially, why should I care that some animal is going extinct? That’s where I like to direct the conversation towards the idea that sustainability happens in really small ways, like even just being aware of climate change is a huge step for some people.”

For the immediate future, however, McElhinny hopes that Environmental Educators will grow its volunteer base at Wake Forest to include more than just students interested in the environment. Sophomore Emy Yamamoto hopes to take over the program after McElhinny graduates this spring.

“I hope the program grows to people in other organizations on campus that aren’t usually represented in sustainability, such as Organization of Latin American Studies or the Black Student Alliance — people who are just interested in volunteering opportunities and might benefit from learning about the environment as they gain the skills needed to teach it,” McElhinny said.

“All students learn differently, so having unique perspectives within our volunteer base from different groups of Wake Forest students could bring something new to our curriculum and potentially speak to other students that we can’t reach in the same way.”