Mental health issues persist post-pandemic

COVID-19-related isolation has exacerbated mental health issues such as depression and alcoholism

COVID-19 made many mental issues worse, especially for young people.

April 6, 2022

In March 2020, the world changed dramatically, with the spread of COVID-19 and the newfound fear that the pandemic generated gripping the nation, forcing people into their homes and redefining daily activities. As people’s lives shrunk to the size of their rooms and the bounds of socialization became constrained to four walls, the country plunged even further into a mental health crisis. And while hospitals and intensive care units filled with those afflicted, millions more suffered in silence, debilitated from a pervasive and silent struggle that would only worsen as the pandemic continued.

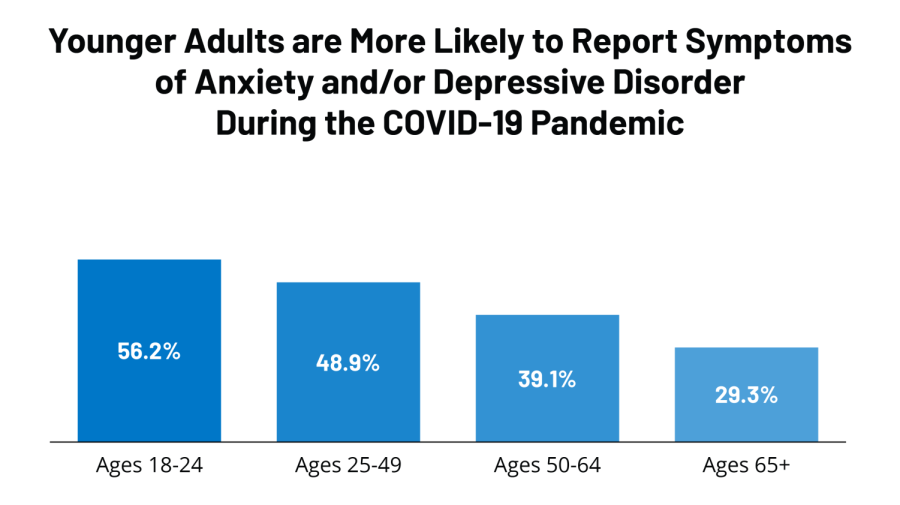

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), anxiety and depression increased globally by 25% during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, women and young people were identified as those most likely to be impacted at a disproportionately high rate and were found to be at an increased risk of self-harming behaviors.

COVID-19 had effects on conditions apart from depression and anxiety, however. In a Massachusetts General Hospital study, researchers found that excessive drinking rose by 21% in U.S. adults. The extrapolated data warns of 100 expected deaths and 2,800 additional cases of liver failure by the year 2023, all attributed to heavy alcohol use due to COVID-19. Aside from the health implications on individuals, researchers noted the relational impacts of such coping behaviors, and the need to examine the societal stigma surrounding mental health and alcohol abuse.

The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism described the positive feedback loop that ensues once alcohol is used to ameliorate symptoms of anxiety and depression. Despite the fact that alcohol temporarily placates the body’s natural response to stress, these fleeting effects wear off and can produce physiological changes in the brain that cause more intense stress responses in the future. As this loop progresses, individuals may consume larger quantities of alcohol to elicit the same response, yielding a higher incidence of liver damage and exacerbating mental health issues.

The increased utilization of alcohol as a coping mechanism is not unique to the COVID-19 pandemic. Other stressors, such as natural disasters, financial burdens, or familial troubles have been demonstrated to also result in elevated alcohol consumption. The longevity of the pandemic and the helplessness associated with restricted and distant social interactions have served as a catalyst for this unhealthy dependency. One main issue that persists amongst those vulnerable to — and experiencing — alcohol abuse, is the prejudice associated with alcoholism and the false conflation between addiction and morality.

The stigma around addiction perpetuates a narrative that separates those afflicted with alcoholism from those not genetically predisposed. The parallel that many incorrectly draw between presenting alcoholic tendencies and possessing a flawed system of values prevents those in need from seeking help and further worsens the fatal silence that prevails over discussions of addiction.

Another issue that arose during the COVID-19 pandemic in relation to alcohol abuse was the difficulty in finding and receiving treatment proved to be. Treatment centers — which sought to prevent the spread of COVID-19 through their facilities — were detrimentally impacted and prevented from admitting patients. Thus, those confined to their homes had unobstructed access to the substances they relied on and little to no access to counseling or in-patient services. Moreover, therapy centers adopted a telehealth model in order to aid in reducing the rate of viral transmission, which dually lowered public health risks while raising the number of those who refrained from seeking help.

COVID-19 has made a multitude of systemic inefficiencies apparent to the general public, with the link between mental health and alcoholism displayed on a stage of unseen proportions. Ultimately, to comprehensively address this issue, the prevalence of alcohol abuse cannot solely be attributed to COVID-19, nor can it be swept under the rug as restrictions and policies ease and vaccinations become more accessible throughout the country. Over these last two years, it has become apparent that mental health must be considered with the same gravity as COVID-19 and must be recognized for its place as an invisible epidemic that has possessed this country and the world.