The brutal aftermath of a sexual assault at Wake Forest

In some cases, students need to relinquish their privacy to receive accommodation from their professors

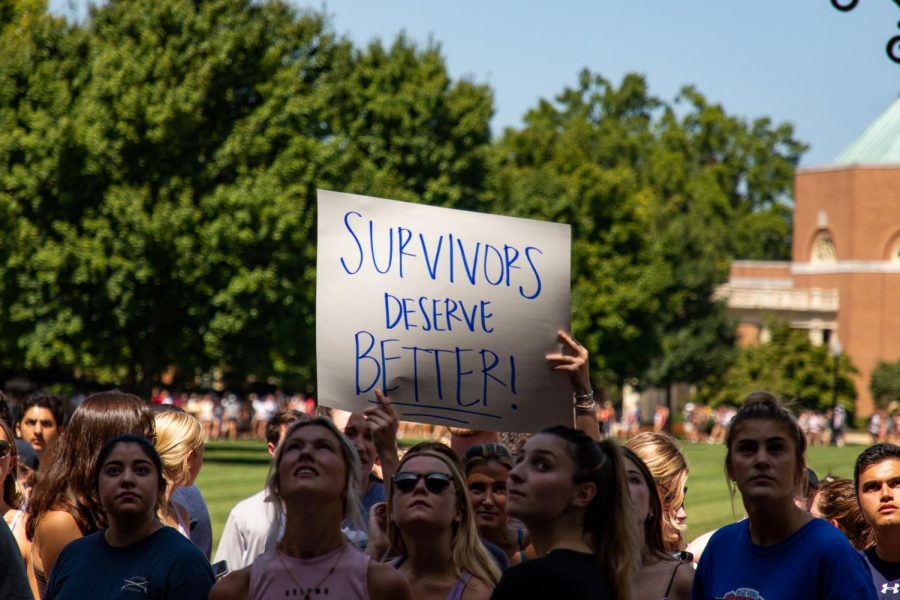

A protest on Aug. 28, 2021 led to increased conversations around sexual violence on campus.

November 30, 2022

On the morning of Saturday, Aug. 27, I was sexually assaulted and left on the sidewalk in front of the unaffiliated Delta Kappa Epsilon (DKE) house.

With no phone or ID, I was left alone to get back to campus and somehow into my dorm building. Without the help of the people that found me, I do not know what else would have happened to me. The post-traumatic stress responses I have faced have made it nearly impossible for me to continue my life at Wake Forest, and they were worsened by the university’s lack of a student-to-professor liaison.

Sexual abuse on college campuses is devastatingly common, and the aftermath of sexual assault ruins a college student’s ability to thrive, let alone make it through a day free from the harrowing stress that stems from the event.

According to a 2019 Campus Climate Survey conducted by the Association of American Universities (AAU), 13% of all college students experience sexual assault, and the aftermath can be catastrophic. Wake Forest is no stranger to these instances. In the 2021 Wake Forest University Campus Climate Survey, 16.3% of all respondents experienced sexual assault. Post-traumatic stress is prevalent for many survivors and severely impacts life on campus, engendering devastating side effects. Memory loss leads to rapidly declining grades, neglect of social commitments and a constant foggy feeling of confusion. Focus also dissipates, making it difficult to finish assignments and put enough effort into extracurricular activities. Isolation quickly sets in, as friends who are unable to understand feel more distant by the moment. Recklessness becomes a threat to personal health and safety. Stress involving schoolwork intensifies as any break taken quickly turns into a massive burden. With family often far away from students, support systems feel few and far between. These common side effects of post-traumatic stress often only get worse as the trauma roots itself into survivors.

The consequences of experiencing sexual assault are extremely infuriating to realize. Having a glaring “W” now appear on a straight-A transcript. Being replaced by a professional in orchestra. Working tirelessly to catch up on five weeks of missed classes. Realizing the assaulter doesn’t even remember who he has hurt. Being unable to attend football games in fear of seeing him. Having any sense of security ripped away. Feeling numb. Feeling insane. Becoming panicked in crowds. Falling apart when catching a glimpse of him on campus.

Having to relinquish privacy in order to make professors understand the situation.

Wake Forest has several wonderful resources to help survivors. The Safe Office has incredible counselors willing to aid students in every way that they can, the Center for Learning Assistance (CLASS) Office helps students create plans and the Office of Academic Advising (OAA) provides ample information about classes. However, for students who have just experienced a traumatic assault, the weight of communicating with professors and managing academics is unbearable. Wake Forest does not have anyone or any office to act as a liaison between students and professors. Accommodations such as extra absences and test time can be given to students, but the reasoning and level behind these accommodations vary greatly between students, giving professors no other insight. Wake Forest doesn’t have a system that can serve as a genuine excuse on students’ behalf. This position simply does not exist.

As a result, students are forced to give up their own privacy by explicitly telling each of their professors about the assault in hopes of making them understand absences, declining grades and late assignments. Survivors are saddled with this huge responsibility, and there is no one to help them. Emailing each professor with more details than necessary is jarring, panicking in front of them during office hours feels mortifying and facing them in class after having to reveal something deeply personal is horrible. Everything is situational — the survivor can only hope their professors will reason with them, and professor responses vary.

Carrying the weight of trauma is enough for survivors. Having to manage communicating with professors entirely on their own is exhausting, nerve-wracking, deeply upsetting and extremely unfair. It is one of the many ways that students face “survivor punishment”. Wake Forest needs to implement more formal and discretional — yet genuine — resources that provide students with the excuses they need from professors. There needs to be someone to help students who are barely holding on to begin with. Students are falling apart and feeling as though their futures have been ruined due to their declining academic performance and worsening mental health.

It is never the survivor’s fault, and it shouldn’t be up to them to try and piece their life back together after being assaulted, especially not when Wake Forest has so many other resources and more than enough funding.

Recently, I had the opportunity to speak at a student panel about campus resources. Sitting in front of President Wente, the Dean and several department heads I explained my experiences involving the lack of resources for survivors. I spoke with passion rather than anger, and I know that those in charge at Wake Forest are genuinely doing their best to listen to students.

This is not a linear journey. Most of my days are poisoned with terrible trauma responses because of what I have been through. But I am very hopeful for the changes that are ahead of us. If you are a survivor of sexual assault, know that I understand you, that I am fighting for you and that spring is coming.

anon • Feb 15, 2025 at 7:19 pm

Lauren –

Over 2 years later, this article remains to be revolutionary. I am going through the same thing right now, during my senior year. Your willingness to share your story is vital, and this article will speak VOLUMES until Wake Forest University takes serious, REAL action against fraternity violence.

Thank you, thank you, thank you.

Anonymous • Dec 2, 2022 at 1:55 pm

Thank you for being so brave & sharing this, Lauren — it means so much to other survivors. SA trauma makes everyday life on campus a huge challenge. I hope we see stronger actions from Wake Forest, especially towards IFC. Greek life feeds violence on our campus and it can’t continue to be this way.

Anonymous • Dec 2, 2022 at 6:47 am

Thank you for sharing this and being the voice for those that might not be able to speak about their experience. You are so brave and strong for bringing this issue into the light, where wake forest needs to take more responsibility and make some real change.

Anonymous • Dec 2, 2022 at 12:47 am

Dear Lauren,

I cannot tell you how much I appreciate you. From my experience, my transcript turned into the alphabet, I spent nights in the library absolutely falling apart thinking of running into them while leaving, the amount of money my parents had to spend finding counselors, CBT sessions, life coaches, psychiatrists, neurologist, (unnecessary, I know, but they were desperate because I kept getting worse) paying for semesters even though I wasn’t able to finish. Wake needs to have better systems in place because the culture that Wake complacently promotes has imposed very direct and damaging effects on many people. My struggle was never taken seriously until it got really bad. I feel like I shouldn’t have to explain myself to get validation from my teachers. They never took me seriously when I say I am struggling. They take it extremely light-heartedly or make me feel like they don’t believe me. They don’t know how serious it is and how much it consumes my life. Why do things have to get extremely bad before we get taken seriously? It was a long road but I am stronger than ever and on track for graduation. I admire you so much for speaking up because it is a huge risk but I support you. I just want to shout out the random posters scattered around wake that send messages about the difficulties of being a boy – did they run out of support for girls?

Anon • Dec 2, 2022 at 12:23 am

Lauren,

Thank you for sharing an experience that feels impossible to convey. Unfortunately you aren’t the first to experience this, I was also in the same spot and spiraled into a pretty deep anxiety/depression, blaming myself, until my rapist was removed from campus for an entirely different charge. These deplorable actions are normalized, encouraged, and perpetuated by both an environment of extreme privilege and groups of men whose “advisors” participated in the exact same actions. In fact, in one experience one of the fraternity advisors, employed by the fraternity to ensure standards were being met, asked the current members to bring a freshman girl to him at a party. This issue is systemic.

Wake Forest – please do better for survivors. Lauren isn’t alone in this and I would suspect that there is also interpersonal violence and abuse happening within the fraternity systems themselves. These are real lives that are forever impacted. It is the university’s duty to protect these young adults from more trauma than what they already have been through.

Anonymous • Dec 1, 2022 at 10:26 pm

You are incredibly brave and you are helping more people than you know. It’s important to realize not only the violence and misconduct of the perpetrator, but to understand the inadequacies of the system aiding students in their recovery. We can’t create change without first recognizing these failings, so thank you.

Anonymous • Dec 1, 2022 at 10:17 pm

“…research suggests that male rape thrives in ‘hyper-masculine’ environments, including some fraternities and sports teams. Research also suggests that abusing alcohol may increase an individual’s risk for experiencing sexual assault—a finding true for both male and female victims” (Coker 180). This is just one example of what research shows us about campus sexual misconduct and hostile masculinity, which is scary and disgusting. I admire your advocacy about the aftermath of sexual assault at Wake Forest. I hope that your story helps others who share a similar lived experience to know they are not alone.

Anonymous • Dec 1, 2022 at 10:03 pm

You are SO incredibly brave for breaking the silence surrounding campus sexual assault. “Speakouts served multiple functions. They called attention to the problem and its widespread nature and worked to change survivors themselves, symbolically throwing off the shame and secrecy that characterize sexual violence (Whittier 2009, 2012; Haaken 2017). Addressing this will call out Wake, the IFC, and the assailant. This also helps support you and everyone who has a similar experience.

Thank you. Stay strong! I’m rooting for you!

Anonymous • Dec 1, 2022 at 8:58 pm

This is so extremely brave of you to share, and so necessary. Thank you for shedding light on such a prevalent subject. Standing with you!

Anonymous • Dec 1, 2022 at 8:42 pm

Thank you for sharing this!!! I hope the Wake Forest administration will address this and support everyone who has similar experiences. You are so so strong!

Anonymous • Dec 1, 2022 at 8:12 pm

Hello Lauren,

Thank you so much for sharing your story and bringing this back to the forefront of Wake discussions. I am indescribably sorry that you had to go through such an awful experience; I admire your perseverance and wish you strength to make it through, however long that process takes. I am glad that you directed attention towards the lack of barriers between the students and the professors. I can’t imagine how difficult it must have been to disclose details about such a traumatic event, and totally agree that a position should be made to address this and handle the situation more delicately. Know that people support you in your advocacy for change in this area. Stay strong. I stand with you.

Jerf • Dec 1, 2022 at 7:32 pm

To quote Anonymous above, “ Wake Forest University needs to hold DKE accountable once and for all. No more closures of the frat and then letting them be recognized again by the university. How many violations of the student code of conduct and incidences like this need to occur until the university says no more?”

A faculty member

Anonymous Alumna • Dec 6, 2022 at 6:03 pm

Of course, any perpetrator(s) should be held responsible under the law, let alone school/organization they belong to.

However, I am confused whether the author is implying the assault involved members of said fraternity, or whether the house was referenced because that is the campus entrance where the survivor was left. I hate to hear any form of assault has taken place, and wish this important detail was clear.

Anonymous • Dec 1, 2022 at 7:14 pm

Thank you for sharing your story. I am so incredibly grateful to you for your bravery and as a recent alumni, I am heartbroken to be reminded of the prevalence of this violence on campus. Specifically, I am consistently appalled how deeply entrained this culture of violence is into the IFC system and consistently within specific chapters on Wake’s campus (which are frequently brought up and infrequently addressed). Your bravery speaks to the masses of others on Wakes campus who have experienced similar violence, both spoken and unspoken. I am proud to be a part of a larger community of women who have had to overcome PTSD from this trauma and who work to prevent the same suffering for others. You are stronger than you know and you are making waves in an incredibly harmful, violent, and deeply misogynistic system.

Anonymous • Dec 1, 2022 at 8:41 pm

Thank you for commenting on this OGB article. The fact that you’re a recent alumni and not much has changed about certain chapters and the IFC system saddens me. As a current Wake student, I worry that Wake Forest won’t handle this in the way it should. Too many times, things get swept under the rug because of privilege, power, and lack of evidence. We need to work together as a community to prevent the suffering of more women! Wake can educate us about the confidential and non-confidential resources on campus, but focusing on resources rather than implementing preventative measures/taking action against DKE are two completely different things.

Anonymous • Dec 1, 2022 at 6:50 pm

This is an amazingly well written article! It must have been difficult for you to share this, but I have a feeling that you will help to make positive changes so that others will have a better experience navigating through the system if they need help. This may be a movement that starts at Wake and then is picked up by other schools as well.

Anonymous • Dec 1, 2022 at 6:28 pm

Your bravery in sharing your story will make the difficult path less unnecessarily difficult for other victims who follow you. Unfortunately there will be future victims. But your courage to bring this gap to light should motivate positive change. Hopefully….

Thank you. And wishing you the best going forward.

Anonymous • Dec 1, 2022 at 5:12 pm

Thank you for sharing this. It’s incredibly important this this is brought to light, because unfortunately, it is all too common.

Anonymous • Dec 1, 2022 at 4:37 pm

Thank you for sharing this with us and for bringing awareness to the prevalence that sexual misconduct has on Wake’s campus. I stand with you.

Lauren Carpenter • Dec 1, 2022 at 5:17 pm

Thank you so much!!! This support means everything to me!

Anonymous • Dec 1, 2022 at 4:28 pm

Thank you for sharing this with us, Lauren. Wake Forest University needs to hold DKE accountable once and for all. No more closures of the frat and then letting them be recognized again by the university. How many violations of the student code of conduct and incidences like this need to occur until the university says no more? Thank you for drawing attention to the pain and difficulty in seeking academic accommodations in the aftermath of this trauma. I stand in solidarity with you and hope others will too.

Student in WGS 150-B

Lauren Carpenter • Dec 1, 2022 at 5:18 pm

This is so kind, thank you so much! I am so happy that we have a community of people who are fighting and who understand!!!

Anonymous • Dec 1, 2022 at 4:07 pm

The perpetrator needs to be exposed and expelled.

anonymous • Dec 1, 2022 at 4:01 pm

Thank you for sharing this lauren, and fighting on the behalf of other sexual assault survivors at wake. i stand in solidarity with you

Lauren Carpenter • Dec 1, 2022 at 5:20 pm

Thank you so much!!!! It is so wonderful to know that people have read this and care about it; I am so grateful for your support!!!!!!

Jayati Lal • Dec 1, 2022 at 3:15 pm

Thank you for sharing your story, Lauren. For shining a light on the issue of campus sexual assault at Wake. For fighting on behalf of other student sexual assault survivors. For drawing attention to the pain and difficulty in seeking academic accommodations in the aftermath of this trauma. I stand in solidarity with you.

Jayati Lal

Visiting Associate Professor, WGSS, WFU

Instructor, WGS150-A/B/C

Lauren Carpenter • Dec 1, 2022 at 5:21 pm

Thank you so, so much!!! It is so wonderful to have faculty support on our side!!!!

Anonymous • Dec 1, 2022 at 12:05 pm

Thank you for sharing this with us and helping bring this problem more light. We will not let this get swept under the rug.

Lauren Carpenter • Dec 1, 2022 at 5:22 pm

Thank you so much!!!!