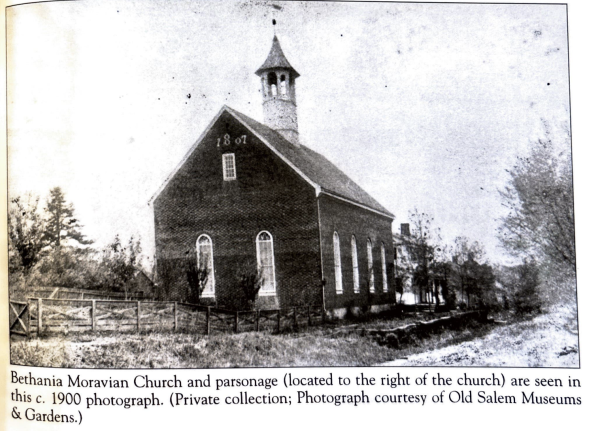

At midnight on Jan. 15, 1812, in Salem, North Carolina, the sky is dark and the temperatures are dropping. A snowstorm had swept through town just a few days before. In the stillness, hymns pierce through the midnight quiet.

Johannes Herbst lays sick in his bed with pectoral dropsy. His Moravian brothers and sisters gather around his deathbed to sing as his soul departed earth. Three days later, Herbst was buried in God’s Acre, the Moravian cemetery in Old Salem that is still there today.

Music was, and still is, central to Moravian life. The church believed that music held the power to transform even the most mundane of tasks into an act of worship. Music made things sacred. The founders of the Moravian church believed that “all of life should be a liturgy.” Even death.

***

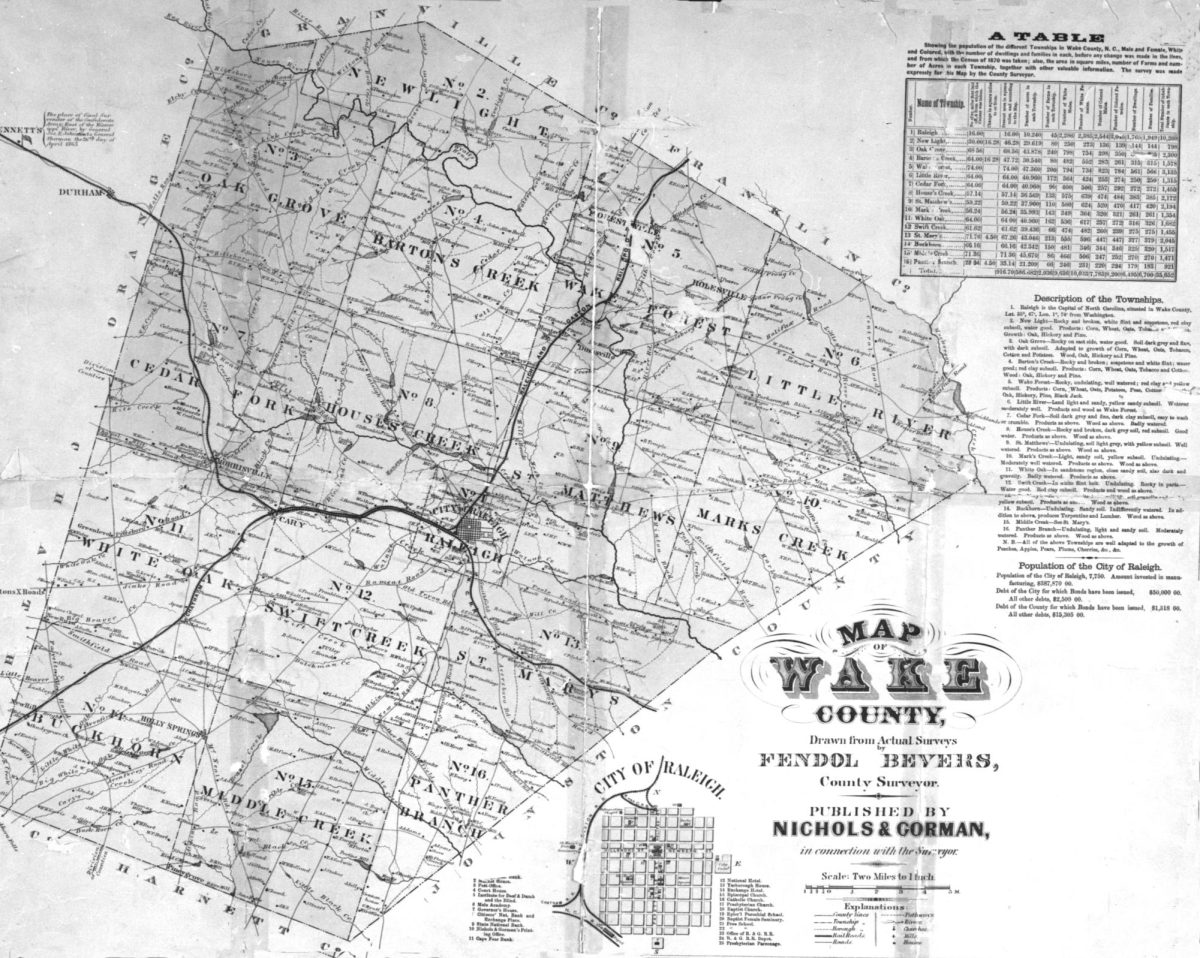

The city of Winston-Salem has an artistic DNA. The country’s first local arts council was established here in 1949. The city is home to UNC School of the Arts, a prestigious public arts school. Legendary artists and bands began their careers here and influenced music far outside of Winston-Salem. Hang around the galleries and coffee houses long enough, and you’ll notice that many locals have an eye for beauty and the hands to craft it. Those roots can be traced back to the city’s early settlers — the Moravian communities of Bethabara, Bethania and Salem, who lived their lives as liturgies.

“As you go back to the earliest history of the first settlers of this area of the country, they were proponents of art and created art and music. This town has followed in those footsteps ever since,” said Richard Emmett, owner of the music venue The Ramkat who has worked at Winston-Salem arts nonprofits.

As the city grew in size, population and infrastructure, the music changed with it. Each decade brought a new sound. Any attempt at capturing Winston-Salem music in a singular story would fall short. It’s too vast. There are bound to be omissions. Nonetheless, there are stories worth telling. If the city’s churches, streets, drink houses, high schools, clubs and concert venues could talk, they’d tell story after story of the city’s rich musical culture that’s been alive since the 18th century.

***

It is Salem’s great fortune that Herbst moved from Bethlehem, P.A. — the other epicenter of Moravian life in the United States — to serve as a bishop in the Salem church just months before he died. Because he is buried here, historic Old Salem is home to Herbst’s extensive music collection that he brought with him when he moved.

The collection includes about a thousand anthems that he copied by hand. These songs are works of art to behold with both the ear and the eye. After spending his days working in the church, he transcribed Moravian music by candlelight at night. His copy is clean and crisp with few mistakes or scratch-outs.

The Moravians preserved Herbst’s copies, along with thousands of other records from their early days. Each town had a diarist who wrote an entry every few days, noting facets of community life such as who moved to town, who led the day’s litany and even what the weather was like. They preserved documents, maps and instruments. Through these archives and stories passed through posterity, we know how music defined Moravian life.

Moravians held daily services where they’d sing hymns. Music also accompanied events like weddings, funerals and the arrivals and departures of congregants. To the surprise of some, Moravians also performed music to entertain, playing compositions by more avant-garde artists of the time like Mozart and Beethoven.

“For them, music was not just something they did in church,” Christopher Ogburn, director of programming and resident musicologist at the Moravian Music Foundation, said. “It was something that existed in all aspects of their life.”

***

In 1913, the municipalities of Winston and the Moravian Salem merged to form Winston-Salem. By that point, tobacco was fueling the Winston-Salem and Forsyth County economy. Downtown began to attract farmers to sell their tobacco crops. The markets also attracted bluesmen from all over the South, who saw an opportunity to put a hat on the ground and strum their guitar. They had the music, and the farmers had the money.

Preston Fulp, born in 1915, often played the tobacco auctions in Winston-Salem beginning in the late ‘20s going into the ’40s. While he’d make a meager $5 for a week’s worth of work at the sawmill, he’d come home with $100 after a weekend at the auctions.

“What made Preston distinctive was that he was equally skilled at playing music from the Black blues tradition and the white country-music tradition,” writes the Music Maker Foundation in the nonprofit’s profile of Fulp.

At that time, the dance halls were segregated. In one dance hall in Mount Airy, Fulp would move from one side of the room to the other, playing blues for the Black folks and country music for the white crowd.

Ernest Thompson from Clemmons is recognized as one of the first “hillbilly” artists — referring to white southern string band musicians — to record music in 1924. Three years later, OKeh Records sent a team down south to Winston-Salem to find musicians not heard in big cities like New York or Chicago. They recorded the hillbilly group North Carolina Cooper Boys at the old West End School, which was one of the earliest sessions outside the music hub of New York City.

Out of this period, came a whole host of talented Piedmont blues and American roots artists who were either born in Winston-Salem or lived here for a stint: Haskell “Whistlin’ Britches” Thompson, Macavine Hayes, Captain Luke, Willa Mae Buckner and Guitar Gabriel. Many of these artists and their work were shortly forgotten after their careers waned.

Many consider this style of music to be the roots of American music. Tim Duffy, a visual artist and musician living in Carrboro, is committed to tending it.

***

In 1990, Duffy was a graduate student at UNC-Chapel Hill working for the Southern Folklife Collection documenting a bluesman named James “Guitar Slim” Stephens. When Stephens was dying of cancer, he told Duffy that if he truly wanted to understand the blues, he needed to find a man named Guitar Gabriel, who was now in his late 60s. So his search began.

Duffy was living in Winston-Salem at the time, and he kept asking around about the elusive Guitar Gabriel, to no avail. One day Duffy got lucky. He was substitute teaching at Kimberley Park Elementary and asked his students if they knew him.

“He’s my neighbor,” one kid said.

The student gave him directions, and Duffy found Gabe’s son Hawkeye, who took him to his apartment. Gabe came out the door, hugged Duffy and said, “I know where you want to go. I’ve been there before. I can take you there.”

Gabe became Duffy’s guide to Winston-Salem drink house culture. Drink houses are residential homes that illegally sell alcohol by the drink, common in Southern Black neighborhoods.

“These are long-standing places — they’re like community centers,” Duffy said. “The bigger ones are running 24/7. They sell liquor and dollar shots.”

Gabe and Duffy started making music together, playing at different drink houses and clubs across Winston-Salem. Being immersed in this scene of older blues players, he realized the poverty these musicians were battling.

“The record industry really didn’t work for these guys,” Duffy said. “No one really believed that these guys were any good. I knew they were great. It was hard to get any recognition for them.”

The idea for the Music Maker Foundation was born in Winston-Salem in 1994. The nonprofit is committed to excavating the “best music you’ve never heard.” They focus on certain music traditions from the South: blues, gospel, string band, folk, Native American and singer-songwriter. And they financially support a certain type of artist: musicians over 55 years old who live on less than $25,000 a year. The foundation helps artists find recording opportunities and book performances as well as receive medical care and access to affordable housing.

While not a part of the Music Maker’s band of artists, The 5 Royales are another group of musicians from Winston-Salem who waited far too long to get their due.

***

Lowman Pauling was working in the kitchen at a Wake Forest University dining hall in the late ’80s, and he showed a co-worker his 45 record of The 5 Royales’ “Dedicated to the One I Love.”

“Man, my dad loves that song,” his co-worker said.

“My dad wrote that song,” Pauling said.

“Naw, I don’t wanna hear that.” He didn’t believe him.

“I’ll bet you $20,” Pauling said. He pulled out the record and pointed to his father’s name on the cover. “What does that say?”

“Lowman Pauling,” the man said.

“What’s my name?”

Pauling left $20 richer.

It was at this moment that Pauling realized that when someone doesn’t believe you when you tell them who your parents are, your parents are probably a big deal.

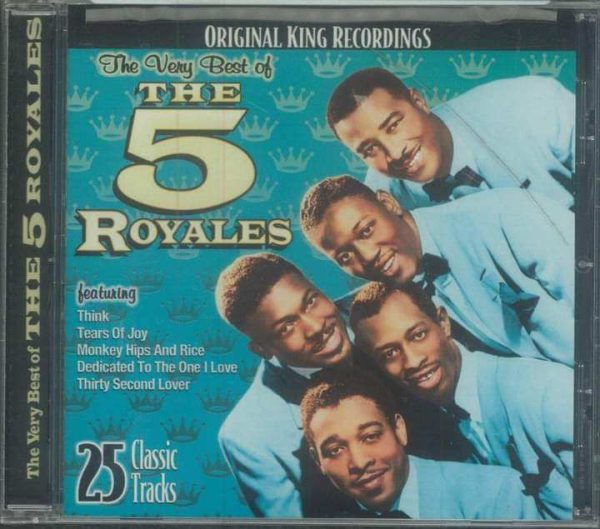

Pauling’s father, also named Lowman, was the lead singer and songwriter of the R&B group The 5 Royales. Other members included Otto Jefferies, Johnny Tanner, Obadiah Carter and Jimmy Moore. Jefferies eventually left the group and was replaced by Eugene Tanner, Johnny’s brother.

The 5 Royales began as a gospel group called the Royal Sons Quintet in 1951. They played gospel concerts at churches all over east Winston-Salem.

They didn’t sacrifice their gospel roots when they transitioned into a fully R&B group. What made them unique was that they combined the gospel sound with R&B lyrics.

“They were not unlike any other group with a church background,” Fred Tanner, the brother of group members Eugene and Johnny said. “But when they left to go to R&B they knew nothing other than that style of singing. That was what made them unique.”

This style paved the way for artists like Ray Charles, James Brown, Aretha Franklin and Steve Cropper. Those artists gained more recognition for their careers than The 5 Royales.

Some of the group’s greatest hits were even made more popular by other artists. “Dedicated to the One I Love” was a major hit for both The Shirelles and The Mamas and the Papas. “Think” was a hit for James Brown. “Tell the Truth” was successfully covered by Ray Charles. Chuck Berry even copied how Lowman Pauling played — with his guitar slung low at his knees. The group created the ladder for others to climb, but they never reached the top themselves by standards of commercial success.

Ray Charles, James Brown and Chuck Berry were among the first 10 inductees into the inaugural Rock & Roll Hall of Fame Induction in 1986. Aretha Franklin was selected the next year. The 5 Royales had to wait until 2015 — an honor that was long overdue. Unfortunately, none of the band members were alive to experience their induction. Their relatives accepted the prize on their behalf.

Fred Tanner, brother of Eugene and Johnny, says the group never received the same acclaim because they were ahead of their time and among the first to adopt their sound and style.

Even the band’s own hometown did not give The 5 Royales the attention they deserved. Lowman Pauling’s name was spelled wrong in his obituary, which was just a small blurb in the Winston-Salem Journal. His headstone had the wrong date of death.

“In highly segregated Winston-Salem, the Royales were beloved within the Black community but largely ignored by white society, with little mention of their achievements in the mainstream press,” Lisa O’Donnell, a reporter at the Winston-Salem Journal, told Cleveland.com. O’Donnell has written extensively about The 5 Royales for the paper.

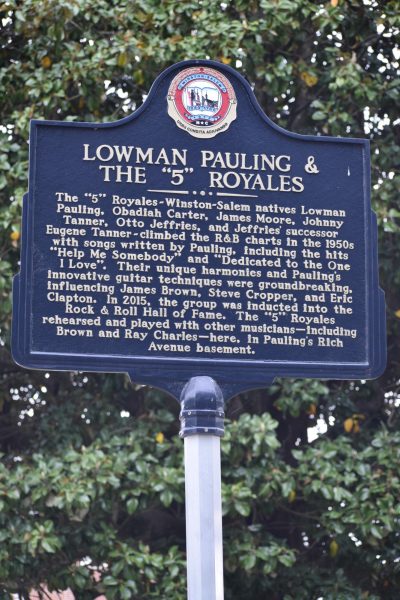

Now, there are physical symbols of The 5 Royales’ success. Winston-Salem named a street “5 Royales Drive.” The city placed a historical marker in front of Lowman Pauling’s home on Rich Avenue, where the group rehearsed and often welcomed guests like Ray Charles. The group has a star in Winston-Salem’s Walk of Fame. This spring, the city is expected to unveil a mural in their honor on the east-facing wall of the Big Winston Warehouse building on Trade Street, across the street from The Ramkat.

The 5 Royales split up in 1965 but their influence on rock, soul and R&B lives on. In the next two decades, Winston-Salem began to nurture a new sound of punk, alternative and rock.

***

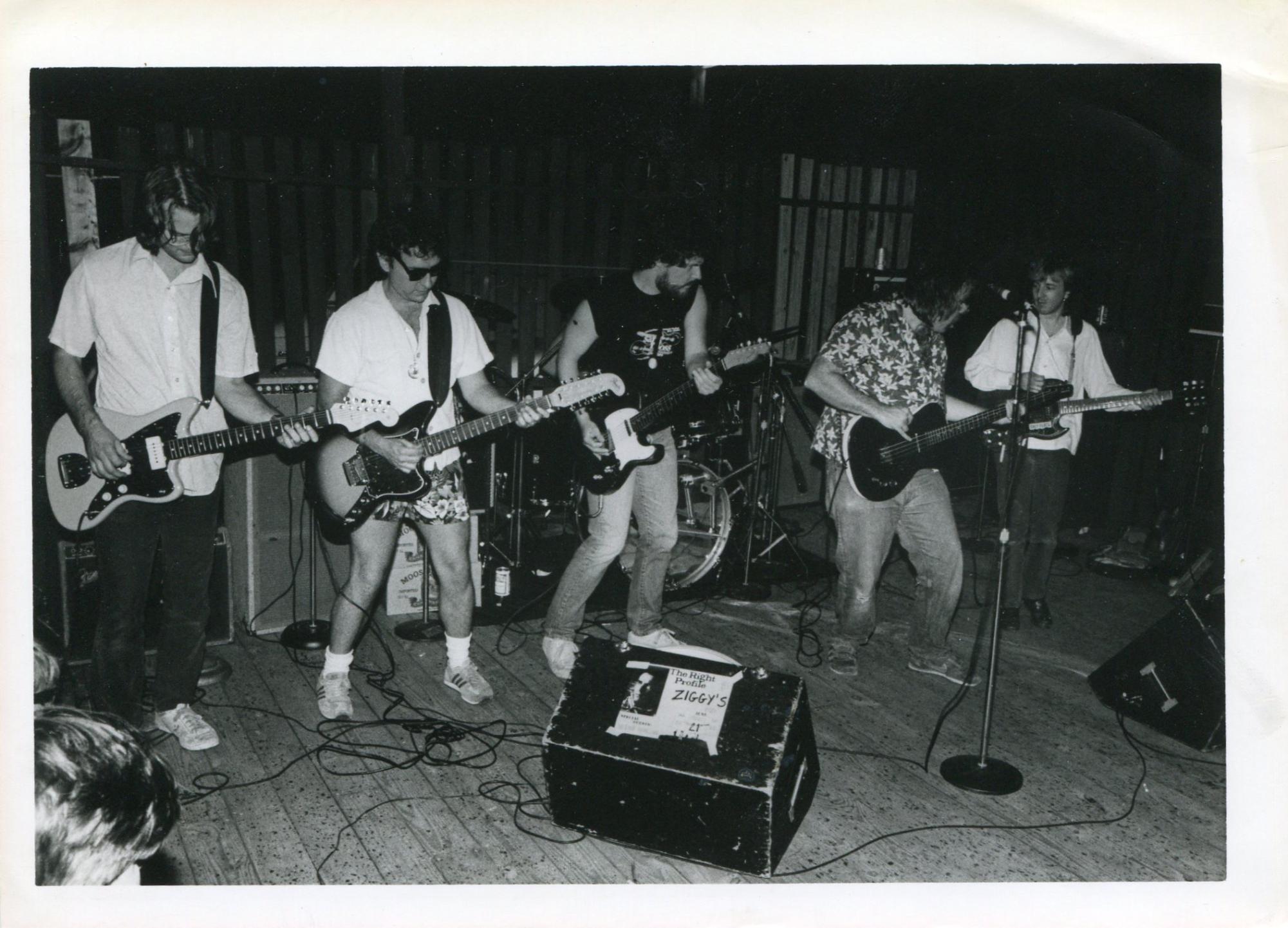

Central to any band’s story are the places where they played. These spots are the setting of the origin story, the breeding ground of talent. For the aspiring rock talent of the late ’60s and ’70s in Winston-Salem, this city was the perfect training ground.

Mitch Easter, Chris Stamey and Peter Holsapple, among other aspiring musicians, were all teenagers just starting to play guitar and write songs in garages in the late ’60s. The three played in a variety of bands through high school and college, often with each other. They would later go on to play and produce music professionally. Easter produced R.E.M’s early albums, and Stamey and Holsapple went on to form the dB’s.

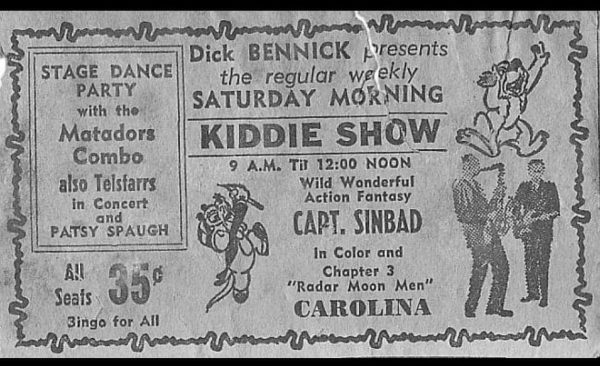

These guys got good because they had chances to play every weekend, and not at clubs at first. Instead, they played unlikely places — Saturday morning Kiddie Shows and churches.

Kiddie Shows were concerts exclusively for young people held on Saturday mornings at the Carolina Theatre, now the Stevens Center. Kids from 7 years old to young teens would attend. One poster advertises admission as costing 35 cents, and for that price, kids could see some of the best young bands around. The shows were hosted by Dick Bennick, a DJ at the local radio station WTOB. Many accredit him as the man who brought rock ‘n’ roll to young people in Winston-Salem during the ’60s. Because of these shows, teenage bands were able to play on the Carolina Theatre stage, just like rock stars.

“It had velvet curtains on a huge stage, and it really felt like ‘Okay, this is show business,” said Easter, who remembers playing there with one of his early bands Sacred Irony and Imperturbable Teutonic Griffin. Yes, you read that right.

Sacred Irony and Imperturbable Teutonic Griffin were just two of the local bands to refine their craft at Kiddie Shows. Others included The Teen-Beets, Shadows of Thyme, The Versatiles and Captain Speed and the Fungi Electric Mothers.

Easter, Stamey and Holsapple were a part of a group at Reynolds High School who coined themselves the “Combo Corner.” A combo refers to a small band, but it wasn’t cool to say at the time. It was something only parents said to sound cool. These guys adopted the phrase ironically and called themselves the “Combo Corner.” They would sit in the parking lot before the bell rang, play and talk band stuff. Their long hair easily distinguished them from the jocks or the nerds.

In the ’70s, churches began to open up their dance halls and community centers for teens to play music at. Ardmore Methodist, Highland Presbyterian and Knollwood Baptist, among others, all invited teenagers to see bands play on Friday and Saturday nights. The gatherings are often referred to as “coffeehouses.”

Churches across the country were condemning rock ‘n’ roll as the “devil’s music,” but in Winston-Salem, churches were hiring bands and inviting the youth to enjoy it.

“Around the country, people were going into pulpits and denouncing this stuff,” Ed Bumgardner, a former music critic at the Winston-Salem Journal and local musician himself, said. “Around here, they were paying the kids.”

At bars, bands would have felt pressured to play the top hits of the day. At the churches, however, teen bands felt the freedom to play whatever they wanted, including original songs.

“It’s hard to overemphasize the importance of this: By opening their doors, the churches played a huge role in fostering creativity in the Winston-Salem music scene,” Chris Stamey writes in his book “Spy in the House of Loud,” which chronicles his time growing up in this golden age of rock music in Winston-Salem before he moved to New York.

Bumgardner remembers catching shows at the churches to see what talent was out there because he was trying to learn how to play. This is where Bumgardner saw Sam Moss and Chuck Dale Smith play with their band Imperturbable Teutonic Griffin.

“We’d just sit there and stare. Open mouths,” Bumgardner remembers.

Moss was a larger-than-life figure — a legend among the young musicians of the late ’60s and ’70s. He taught many of them how to play, or how to play better.

“He was just such a sort of towering figure among us teenagers,” Easter said. “He was such a good musician. Just being around him just made me get better.”

When Moss died by suicide in 2007, Bumgardner wrote his obituary for the Winston-Salem Journal titled “A beautiful eulogy to the guitar god no one’s heard of.”

“To all who crossed his path over the past 40 years — particularly musicians and music fans — Moss was the quintessential guitarist of Winston-Salem, a master of the instrument by any standard,” Bumgardner wrote.

In his ode to the musical legend, Bumgardner says to honor Moss by playing “Happy” by The Rolling Stones and turning the volume all the way up. It was one of his favorite albums, and Bumgardner says that lyrics say all that needs to be said about Moss.

Keep on dancin’

Keep me happy

Keep on dancin’

Keep me happy

***

The burgeoning of rock in the ’60s and ’70s paved the way for Winston-Salem to gain national acclaim in the ‘80s. The dB’s rose to prominence in this decade, becoming an influential band in the jangle pop and indie rock genres. Although formed in New York, the band was always closely affiliated with Winston-Salem.

Easter opened The Drive-In Studio in 1980, which operated out of his parents’ garage and attracted nationally acclaimed talent. It was here that he produced R.E.M.’s debut single “Radio Free Europe.” The Drive-In closed in 1993, and Easter now operates Fidelitorium Recordings in Kernersville, a private residential recording studio. The Avett Brothers, Mandolin Orange (now Watchhouse) and Rainbow Kitten Surprise have all recorded sessions there.

Two iconic clubs — Ziggy’s and Baity’s — opened around this time and brought national acts to Winston-Salem. Bumgardner remembers that on any given Friday or Saturday night the two clubs would be packed.

“For here, these places were palaces — rundown palaces — but palaces,” said Bumgardner, who not only covered performances at these clubs for the Winston-Salem Journal but also played there with his band The Allisons. “It was exciting. It was great. Live music still hadn’t become greed-driven. Bands were just begging to play at Ziggy’s and Baity’s. They were turning down big bands. They really wanted to play there.”

Places like The Werehouse (now Krankies), Club Hellenbach and Pablo’s (later 533 Uprisings) hosted more underground artists. The popular punk bands in Winston-Salem like Squatweiler, Codeseven and Naked Angels played these spots.

Jonathan Kirby, local musician and music history buff, says that when he went off to college at UNC-Chapel Hill in the late ‘90s and early 2000s, he realized that Winston-Salem’s sound was unique because much of it was original.

“There was never any playing covers in Winston-Salem,” he said. “All the bands that we loved wrote original songs. It made me realize that that was something that was happening here that wasn’t happening elsewhere.”

***

Each interview for this story was a walk down memory lane. The memories first led to Church Street, where the Moravians gathered each day to sing hymns at church. Then to the tobacco auctions on Trade Street, the drink houses on the east side of town and to Rich Avenue, where The 5 Royales rehearsed. The stories traveled back to the Carolina Theatre, the church coffeehouses in Ardmore and the parking lot of Reynolds High.

The places of the music scene look different now. Many iconic, long-time establishments have closed, leaving fewer places to play and a bitter nostalgia for those who remember their glory. Baity’s closed in 1993. The original Ziggy’s on Baity Street closed in 2007, and its reincarnation at Trade and 9th closed in 2016. The Garage closed in 2018. Winston-Salem still boasts strong local talent — they just don’t have as many places to play. The Ramkat, Gas Hill, ALV Nightclub, Monstercade, The Den and breweries are some of the new live music spots. It is only natural for the places of the music scene to change. It has throughout history.

“I’d say what was a club scene turned into a brewery music scene for a lot of the locals,” said Emmett, co-owner of The Ramkat.

Winston-Salem’s music legacy endures by looking both backward and forward. The older generation swaps photos and stories on Facebook groups and blogs. Many of the guys from the ’60s and ’70s rock scene are still playing. The new young artists are carving their own way, establishing new places that will be the backdrop to their stories.

***

While reporting this story, I met three family members of The 5 Royales at a diner on Peters Creek Parkway. As Fred Tanner was telling a story about hearing The 5 Royales on the radio for the first time, a man sitting alone in the booth behind us chimed in.

“I used to lay under the covers at night and listen to WAAA,” the man said. WAAA was the first Black programmed radio station in North Carolina.

Tanner didn’t realize the man was eavesdropping. Since I was facing him from my side of the booth, I could tell he was hanging on to every word. He didn’t know his breakfast would be accompanied by great stories about musical legends he loved. After finishing his meal, I could tell he wasn’t ready to leave yet. He ordered chocolate cake.

Eventually, he got up to leave and stopped by our table.

“You’ve inspired me,” he said. “Thank you.”