Jordan Peele’s new satirical thriller Get Out begins as a young black man walks alone in an affluent white suburb late at night.

By opening the film with a scene that evokes the fear and horror of police brutality that black Americans are all too familiar with, Peele quickly establishes a sense of discomfort that drives the entire film.

As Peele effectively blends genres, invokes horror classics and pop culture and stirs up tension, he creates a film that is both impressively original and familiar — in both entertaining and disturbing ways. Get Out demonstrates that genre films can provide astute cultural commentary while simultaneously entertaining audiences.

When Rose, a white woman, asks her black boyfriend Chris to go to her parent’s home for the weekend, Chris is hesitant. “Do they know I’m black?” He asks. She tells him no — assuring him it’s nothing to worry about — and they head to her parent’s house. However, as the film plays out, we see her unwillingness to acknowledge Chris’ race is a dangerous form of racism in and of itself. The microaggressions Chris endures from the beginning of the film, such as Rose’s dad saying he would vote for President Barack Obama for a third term if he could and a party guest commenting on the size of Chris’ muscles, serve to perpetuate a sense of unease and tension that is present in every scene. Even though Get Out doesn’t become a typical “horror” film until the last third of the movie, the film utilizes shifts of tone, facial expressions, cinematography and the soundtrack to effectively evoke fear from the seemingly smallest occurrences.

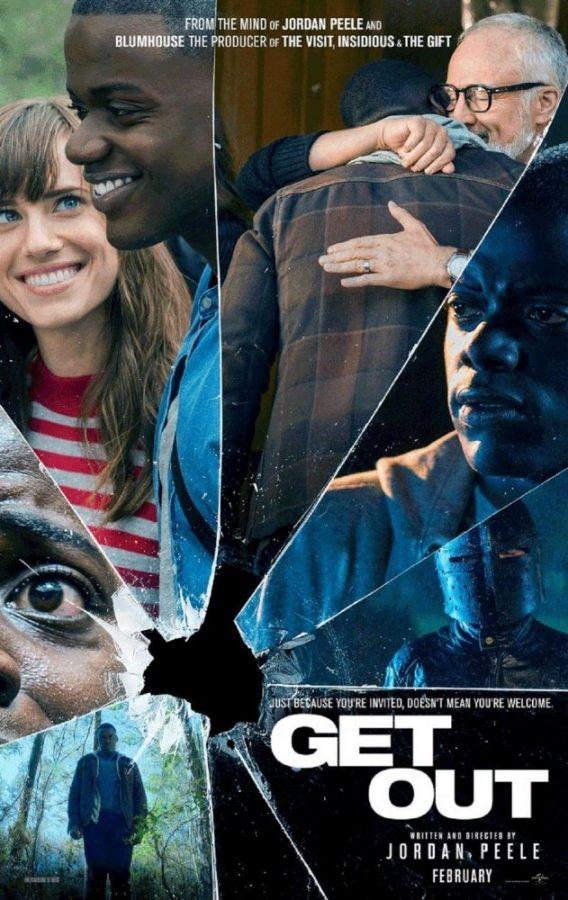

Daniel Kaluuya is excellent as he plays Chris with insight and subtlety. Although the dialogue is sharp and the cinematography and pacing effectively create tension and atmosphere, Get Out would not work without Kaluuya’s ability to evoke fear and empathy from the audience. Allison Williams is also quite good as Rose, a character who demonstrates the common passivity of white moderates and liberals that only serves to perpetuate racism as it suppresses all difficult discussions of race. The genuinely shocking twist powerfully remarks on the commodification of black bodies in the current cultural climate and in liberal spaces. Some of the most terrifying images in the film, such as a shot of a police car with sirens flashing that occurs at the end of the film, purposefully allude to the very real horrors of racism and police brutality that black people face daily.

By exaggerating microaggressions and other forms of racism propagated by the liberal elite to the levels of horror (though I am not trying to say what black people face in the U.S. and worldwide is not horrific), Peele turns the film back on the audience in an attempt to provoke reflection and discourse. The film ultimately asks viewers to examine the racism in their own lives, particularly the more subtle forms of racism that are often perpetuated by the seemingly well-intentioned white “liberal elite.” Get Out is an intense and intelligent satirical film that entertains and disturbs in equal measures.