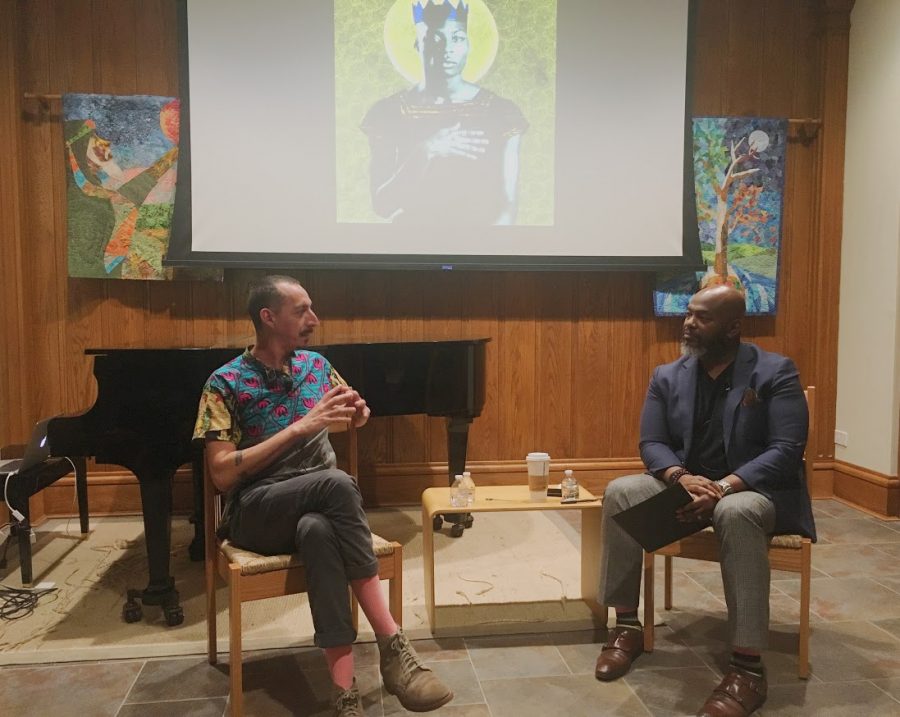

On Tuesday Feb. 28 Gabriel García Román, a queer, Mexican-American artist, discussed his latest series of multi-format works that mimic Catholic religious iconography in a conversation with Derek Hicks, professor of religion and culture in the School of Divinity.

Earlier that day, Román spoke with students, staff and faculty over lunch in the LGBTQ Center and during an open reception prior to the main event in Davis Chapel.

The evening’s dialogue centered on the artist’s series “Queer Icons” which highlights queer and trans people of color who are activists, artists and organizers in their communities.

Román represents his subjects as saints in their portraits, deriving inspiration from fresco paintings of haloed saints in churches like the one his family frequented on the north side of Chicago.

“Walking into church and seeing portraits of saints [is] burned into my memory,” he said. “I was always fascinated with both the strength and vulnerability of these figures and that’s what I tried to incorporate in ‘Queer Icons.’”

Román’s photography project began with taking portraits of friends until he decided to hone in on activists.

“These people are the modern-day saints of their communities but they are often lost in the background,” Román said. “I wanted to help the world see them but also help them see themselves in a new light.”

“In galleries and museums and all the art history courses I would take, I never saw myself or my community represented,” Román continued. “I wanted to disrupt the narrative with this project.”

Sophomore Brianna Reddick, appreciated the philosophy behind Roman’s focus on queer people of color.

“Elevating communities that are often only publicized when tragedies happen and also capturing them as aesthetically beautiful in a society that doesn’t always appreciate their beauty is so important,” Reddick said.

When a student asked Román about how he thinks about the theory of intersectionality in the context of his work, he said “it’s hard because I want to be careful not to tokenize anyone but I do feel like it’s important to focus on trans women of color right now because they’re under attack.”

“Having more positive imagery, even for our own community, would be nice to see and hopefully go a long way to humanize [them],” Román said.

The most recent portraits in his series feature poems or prose written by the subject with the intent of honoring individual voices and stories.

“I don’t like the phrase ‘giving voice to marginalized communities,’” Román said. “[The subjects] are doing that themselves and this work is a matter of honoring them in the most collaborative way possible.”

When asked how he rose to prominence Román cited his active presence on Facebook, Instagram and Tumblr.

“I think it’s awesome that social media can have that impact,” Reddick said. “It makes his work accessible to a lot of people. There’s a huge community of queer millennials of color on Tumblr and other social media outlets.”

“It began as a personal project but this body of work is a lot bigger than me now and no longer mine,” Román said. “It’s my community’s … It’s for the 13-year-old in the South who is on the verge of suicide and needs an outlet to somehow see himself in the future. I get a lot of DMs and messages and the positive emotional reactions I get from people who view the work whether online or in galleries are really invigorating and push me forward.”

Marianne Magjuka, director of democratic engagement at the Pro Humanitate Institute, felt compelled to have Román speak at Wake Forest after discovering his work last year.

“In my work on campus, I see many students who are thinking about questions of religion, sexual orientation, race and immigration and how these things intersect so I thought [Román] would be a different type of speaker for them,” Magjuka said. “An artist who is exploring those very questions in his work.”

For Reddick, this effort did not go unnoticed.

“[Supporting] this event honors communities that aren’t always thought about when planning campus events,” she said.

Although Román shared that he does not think of his work as political Magjuka disagrees fundamentally.

“I think it’s important in our current political moment that we continue to find the time and energy to appreciate art and create it ourselves,” Magjuka said. “For people who are struggling and feeling marginalized and oppressed right now there’s so much to be upset about and fighting against but I really do believe that art is important in so many ways. By bringing him [to campus], I hope that people took from it that the act of creation is important and that any type of work you can create can be political in and of itself.”