Michael Crespi, the director of market readiness and employment at Wake Forest, flipped through a binder compiled of various graphs that show an international student’s process of transitioning from a student to an employment visa.

The U.S. government has implemented a lottery system which grants employment visas, known as H1-Bs, on a yearly basis. However, this process does not guarantee that those who apply will receive an employment visa.

Within the most recent lottery cycle, 199,000 petitions were submitted nationally. However, only 85,000 high-skilled employment visas are distributed each year, according to Crespi.

Therefore, out of the foreign individuals who submitted a petition within the last cycle, only 43 percent were granted an employment visa.

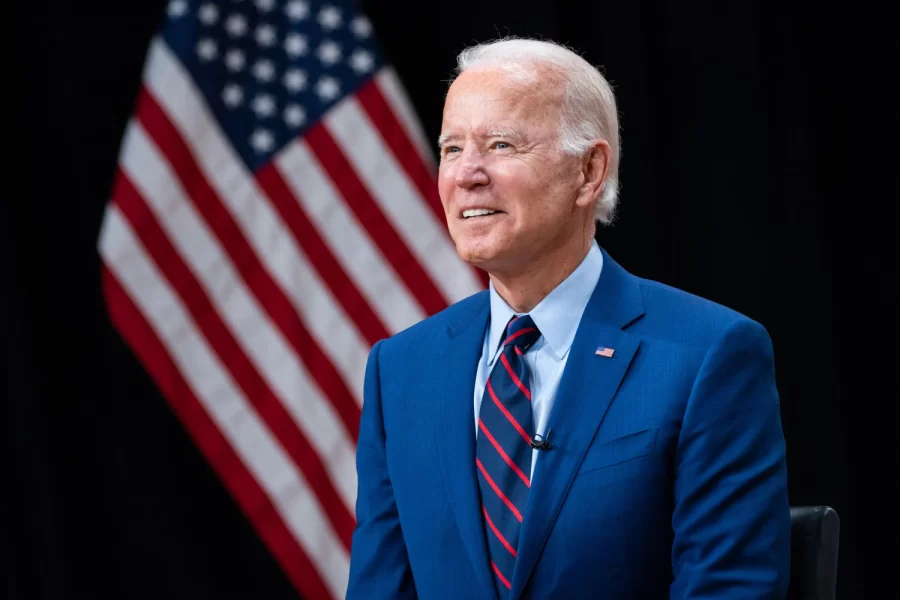

Many Wake Forest international students are eager to remain in the country or at least stay longer to get advanced degrees. Yet, given tougher immigration laws under the new administration in Washington, D.C. and lots of competition for the relatively few work visas granted annually, nothing is certain regarding their future in the U.S.

“Supposedly it’s random, but you never know,” said senior Kedi Zheng, describing selections made within the process. Zheng is an international student from Shenzhen, China.

Crespi stopped turning the pages when he reached a chart showing the increased demand for employment visas, known as H1-Bs, over the past 10 years. With a growing number of foreign individuals seeking an employment visa, the current immigration tension and the changes within company hiring policies, many international students — like many at Wake Forest — are left at the mercy of the application process.

Zheng, along with other international students pursuing employment opportunities in the U.S., will first enter into a work authorization period known as ‘Optional Practical Training’ (OPT) after graduation. Depending on the work of the individual, the OPT transition period is either one year or three years long.

If an individual becomes sponsored by his or her employer, he or she is then eligible to file for an employment visa within the lottery system. If they are selected for an employment visa, this H1-B visa can be valid for up to six years. If they are not selected for an employment visa, by law, they must return to their native country upon their OPT’s expiration date.

H1-B visas are recognized as a pathway process that would lead an individual to apply for a Green Card or more permanent residency status, according to Crespi.

A Comfortable Place To Stay

Originally after the presidential election in 2016, senior Luna Zhou felt uneasy about potential changes to immigration politics. Since realizing the delay within the proposed immigration restrictions, she hopes to stay and work within the U.S. for a couple of years before returning home.

“The starting salary is higher in America than it is in China,” Zhou, an accounting major from Nanjing, China, said. “That would be a big benefit, so I can pay back my parents for the [Wake Forest] tuition.”

Zhou has accepted an offer to intern for PricewaterhouseCoopers’ Charlotte office. She hopes the internship opportunity will transition into future employment, adding “North Carolina is such a comfortable place to stay.”

The accounting industry consists of the ‘Big Four’ firms, including Deloitte, Ernst & Young, PricewaterhouseCoopers and KPMG. Because of their size, these companies have the resources to sponsor international students through the employment visa process.

As a result, an accounting degree becomes far more enticing to international students in the job market that it presents. Many ‘Big Four’ companies recruit students from Wake Forest’s accounting program, which increases the probability for employment sponsorship, according to Zheng.

However, many of these accounting firms have announced plans to stop recruiting and sponsoring international students. This trend suggests companies are becoming hesitant to invest in foreign individuals.

Everyone Loves Science

“I’m from the deep south … like our Florida,” Zheng said, referring to his home in Shenzhen, China. His family’s apartment offers a skyline view of the adjacent city, Hong Kong.

Zheng started studying math, switched to business and then came back around to be a mathematics and computer science major because in his words, “you can’t find passion in [accounting] journal entries … nobody can,” he laughed.

Zheng is a considered a STEM student, because his academic focus falls within the science, technology, engineering and math fields. Because he is a STEM student, Zheng is given three years for his OPT transition period. Non-STEM students only receive one year within the OPT transition period.

Throughout the three OPT years, Zheng will be eligible to resubmit his petition within the lottery system up to three times if necessary. Therefore, an opportunity for him to receive an employment visa is three times greater than that of a non-STEM student.

“The United States has a shortage of programmers and, well, everyone loves science… let’s just put it that way,” Zheng said as he defended the extended OPT period for those within his field.

However, Zheng will not need to place himself within this process immediately. He has plans to attend graduate school, either Washington State or Georgia Tech, for an advanced degree in computer science.

The Product Of Her Future

Asia Wang’s freshman year move-in was her first time in the U.S. Now, the senior accounting major plans to take her professional development to the nation’s capital. Wang has accepted an internship offer with Ernst Young in its Washington, D.C. office.

According to Wang, she generalized that out of the international community at Wake Forest, 90 percent are unsure about their post graduate plans and 10 percent are certain they want to return to their native country after graduation.

Wang falls within that 90 percent of uncertainty category.

She envisions that a majority of international students will apply for an employment visa within the lottery system, however, the potential of not being granted an H1-B visa is of major concern.

Her father had advocated for her to minor in something ‘practical’ such as economics or mathematics. However, Wang decided to minor in politics & international affairs.

“I’m not a product of their future,” she said.

Perturbed Pundit • Oct 21, 2017 at 7:26 am

Why was my initial comment marked as spam? It was completely relevant, on-point and well-referenced. What are you afraid of?

Perturbed Pundit • Oct 20, 2017 at 7:27 am

Both the Optional Practical Training (OPT) program and the H-1B visa are vehicles that put US citizens at a great disadvantage and need to be reformed. Here’s why:

OPT

——

OPT amounts to the government offering a $30,000 incentive to employers for hiring a foreign student instead of a U.S. citizen or permanent resident. This bonus takes the form of the foreign students being exempt from payroll tax (due to their student status, which they technically still have under OPT in spite of having graduated). Why hire Americans, eh?

Since this tax exemption from payroll tax was pointed out in a lawsuit against DHS, and has been one of the major points raised by critics, DHS was well aware of it. Yet they are refusing to address it or even acknowledge it.

In contrast to DHS recent statements, in which they openly admitted that they intend OPT as an end-run around the H-1B cap, they now describe OPT in warm and fuzzy terms of “mentoring” (putting the “T” back into OPT). That raises several questions:

If the U.S. indeed “needs” the foreign students (DHS’s phrasing on this point verges on desperation) to remedy a STEM labor shortage, why do these students need training? The DHS/industry narrative is that the U.S. lacks sufficient workers with STEM training, while the foreign workers are supposedly already trained. And, if workers with such training are indeed needed, why wont these special mentoring programs be open to Americans? Why just offer them to foreign students? Since DHS admitted that its motivation in OPT is to circumvent the H-1B cap, does that mean that if the cap were high enough to accommodate everyone, these same foreign students wouldn’t need training after all?

H-1B

——-

While lobbying Congress for more H-1B visas, industry claims H-1B workers are the “best and brightest”. Come payday, however, they’re entry-level workers.

The GAO put out a report on the H-1B visa that discusses at some length the fact that the vast majority of H-1B workers are hired into entry-level positions. In fact, most are at “Level I”, which is officially defined by the Dept. of Labor as those who have a “basic understanding of duties and perform routine tasks requiring limited judgment”. Moreover, the GAO found that a mere 6% of H-1B workers are at “Level IV”, which is officially defined by the US Dept. of Labor as those who are “fully competent” [1]. This belies the industry lobbyists’ claims that H-1B workers are hired because they’re experts that can’t be found among the U.S. workforce.

So this means one of two things: either employers are looking for entry-level workers (in which case, their rhetoric about needing “the best and brightest” is meaningless), or they’re looking for more experienced workers but only paying them at the Level I, entry-level pay scale. In my opinion, employers are using the H-1B visa to engage in legalized age discrimination, as the vast majority of H-1B workers are under the age of 35 [2], especially those at the Level I and Level II categories.

Any way you slice it, it amounts to H-1B visa abuse, all facilitated and with the blessings of the US government.

The National Association of Colleges and Employers (NACE) has never shown a sharp upward trend of Computer Science graduate starting salaries, which would indicate a labor shortage (remember – the vast majority of H-1B visas are granted for computer-related positions). In fact, according to their survey for Fall 2015, starting salaries for CS grads went down by 4% from the prior year. This is particularly interesting in that salaries overall rose 5.2% [3][4].

References:

[1] GAO-11-26: H-1B VISA PROGRAM – Reforms Are Needed to Minimize the Risks and Costs of Current Program

[2] Characteristics of H-1B Specialty Occupation Workers Fiscal Year 2016 Annual Report to Congress October 1, 2015 – September 30, 2016

[3] NACE Fall 2015 Salary Survey

[4] NACE Salary Survey – September 2014 Executive Summary