This is part of a series highlighting retiring faculty in the Undergraduate College at Wake Forest.

Paul Escott needed to make a decision and choose between one of two doors.

Raised in University City, Missouri – a suburb of St. Louis where Tennessee Williams attended high school – Escott was a patriotic kid and enjoyed reading about American History as a teenager.

As an undergraduate student at Harvard University during the Civil Rights Movement, he hoped to better understand the historical context behind the racial tension that was transforming the world around him.

Escott knew he wanted to be a historian, but he was torn between whether to study Southern History or Urban History as a graduate student at Duke University in the 1970s.

Escott knew he wanted to be a historian, but he was torn between whether to study Southern History or Urban History as a graduate student at Duke University in the 1970s.

To help make his decision easier, he visited the two professors who specialized in each field. His first visit didn’t go so well, though.

“I went to the door of the woman who taught Urban History. I knocked on the door, and she opened it a crack,” Escott said. “I gave her my best presentation of self, and she said, ‘I’m not taking any graduate students.’”

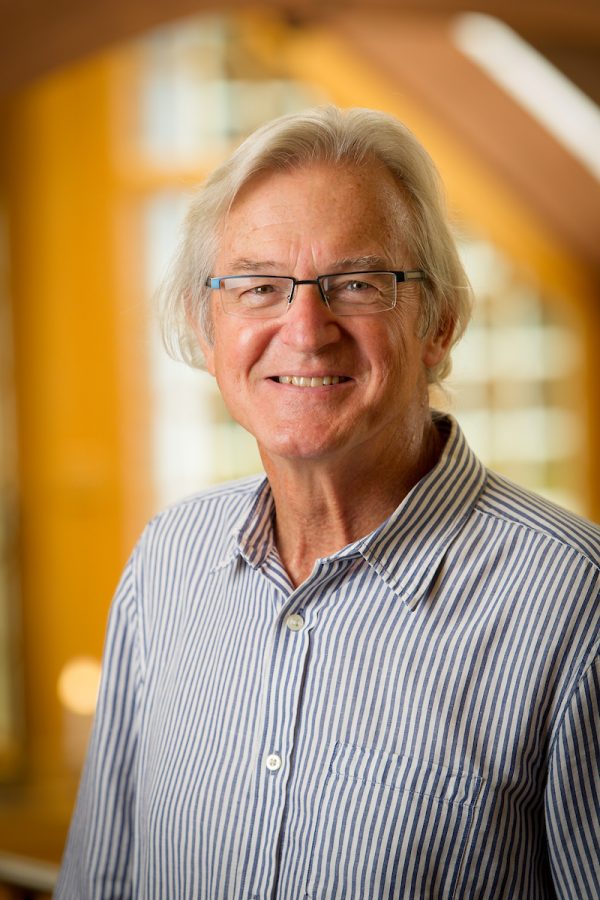

Now recognized as a premier Southern and Civil War historian, Escott sat in his Manchester Hall office on a recent morning and laughed about his awkward encounter with the Duke professor almost 50 years ago.

A prolific writer, Escott has written or co-authored more than a dozen books that have challenged the mythology of President Abraham Lincoln, examined the leadership of Jefferson Davis, and addressed race relations during the Civil War.

A prolific writer, Escott has written or co-authored more than a dozen books that have challenged the mythology of President Abraham Lincoln, examined the leadership of Jefferson Davis, and addressed race relations during the Civil War.

His latest book, Rethinking the Civil War Era: Directions for Research (2018), was released May 4, 2018.

Escott will retire at the end of this semester after spending the past three decades at Wake Forest University, including nine years as the Dean of the College (1995-2004).

“As a teacher, Paul has consistently demanded the best from students, pushing them beyond easy certainties about U.S. History and asking them to question their own assumptions. As a colleague, Paul has been unfailingly generous and has supported many junior colleagues in the development of their own careers. ” Monique O’Connell, Professor and Chair of the Department of History

Escott, the Reynolds Professor of History, is leaving WFU at around the same age that his father – a machinist and foreman in a machine shop – retired.

Being from the St. Louis area, Escott has been somewhat of an outsider as a Midwesterner studying the South. However, his father was born in Kentucky and his mother was raised mostly in Alabama.

“I later realized that I did have somewhat of a cultural understanding of Southern values and Southern ways of looking at the world from being the child of my parents,” Escott said.

Karen Zipf, Professor of History at East Carolina University, met Escott soon after he arrived at WFU in 1988. At the time, she was a History major who had been hired – without a formal interview – to be his student assistant.

“Unfamiliar with Wake Forest, he needed a student’s perspective. As the new guy, he trusted me to show him the ropes,” Zipf said. “For my part, I needed a job, but I also needed a mentor.”

Along the way, Escott challenged Zipf’s thinking about the South in his classes. He taught her about Harriet Jacobs, who had escaped slavery not far from Zipf’s hometown in eastern North Carolina and penned an autobiography about her terrible travails.

Along the way, Escott challenged Zipf’s thinking about the South in his classes. He taught her about Harriet Jacobs, who had escaped slavery not far from Zipf’s hometown in eastern North Carolina and penned an autobiography about her terrible travails.

He also introduced Zipf to the possibility of becoming a History professor.

“I can’t exaggerate the lasting impact Paul had on me as a teacher and a mentor,” she said, adding that over the years Escott has edited her work and “written about 1 million letters of recommendation on my behalf.”

During his time as Dean, Escott helped implement a campus-wide academic plan known as the “Class of 2000.” He also helped raise funds for the Physics, and Health and Exercise Science departments.

When he eventually returned to the classroom, Escott discovered he had a renewed passion for teaching. He had accomplished his priorities as Dean, and he was eager to get back to examining History – even if it meant dispelling some of the popular American narrative.

When he eventually returned to the classroom, Escott discovered he had a renewed passion for teaching. He had accomplished his priorities as Dean, and he was eager to get back to examining History – even if it meant dispelling some of the popular American narrative.

“I think [being a historian] doesn’t make me less patriotic, but maybe I’m more informed about being patriotic,” Escott said. “What will always make me grateful for the United States is that, although my parents didn’t have much money and did everything they could in a substantial way to support me, I really benefited from lots of scholarships.”

But is there a chance his career could have gone in a much different direction had Duke’s Urban History professor opened her door to him?

“I don’t know,” Escott said, laughing. “I’m glad that she did what she did.”