Most college students have experienced the unsettling moment when you start to feel a little soreness in your throat. Suddenly, you realize how fatigued you have been and feel a little warmer than usual. One of the worst, and most common, questions you will ask yourself during your freshman year after feeling that terrible feeling is, “Do I have mono?”

Mononucleosis, or mono, is prevalent on college campuses across the nation and by the age of 30-35, more than 90 percent of adults will have been exposed to it at some point. Typically transferred through saliva, adults love to remind teenagers that mono is commonly referred to as “the kissing disease,” but kissing is only one way you can get it. Mono can be spread through coughing, sneezing, drink-sharing or even sex. Once someone has the disease, symptoms range from fatigue, sore throat, swollen lymph nodes and enlarged spleen.

With such a ubiquitous disease lurking around your everyday life, it may be beneficial to know how mono actually infects the body — and also what your body does to stop it.

Something called the Epstein Barr Virus (EBV) is the biggest cause of mononucleosis and a part of the herpesvirus family. Only 180 nanometers, this nasty virus is surrounded by something called a capsid, which acts as an armor protecting the virus’ essential genetic material. There are also a series of viral glycoproteins surrounding the EBV organism, which works in its favor during invasion. This virus has the potential to infect your B cells, which are typically the cells in your body that produce the antibodies to fight disease, or epithelial cells on your skin or in your mouth.

As EBV approaches your body, possibly from that soda you shared with a mono-infested friend, the viral glycoproteins interact and bind with the cell membrane of your B cells and fuses directly in. Once the virus enters the cell, it can shed that protein armor and get to work infecting you by integrating its genome with your own.

If you have ever had mono, you may have wondered why student health tells you that it will take 4-6 weeks after exposure to figure out if you actually have the virus. This delay is due to something called a “latent period,” which is the time between a person being infected and when they actually start showing symptoms.

The reason mono has such as long incubation time while infecting B cells is because, in order to replicate, the viral genome must be linear. EBV is originally characteristic of a circular genome, so it must linearize before actually becoming fully fused with your genome.

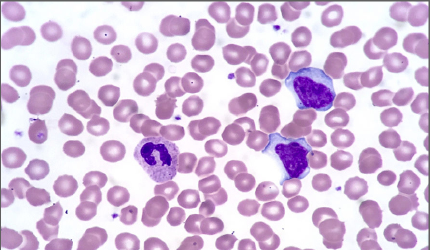

Once the viral genome has straightened out and your lymph nodes are sufficiently swollen, the virus enters something called lytic replication. The lytic cycle of a virus tends to seem counterintuitive because it is literally the process of self-destruction. When EBV officially infects the cell, it can replicate within the host, then destroy the cell so that it can spread to other cells in your body, proving this process extremely beneficial. With this mass of infection, a lymphoblastoid cell appears in your body, which is really just a swollen lymphocyte, and provides the perfect location for indefinite growth of the virus.

After about three weeks, your body’s immune system will have worked hard to overtake the EBV cells and create antibodies and defense mechanisms against this pesky virus.

Eventually you will feel healthy again, instead of feeling like a sloth that sleeps most of the day, but mononucleosis never truly leaves your body after infection. You will continue to carry the dormant form of mono throughout your entire life, but have no fear, your body has created an entire line of defense to fight any reactivation of the virus. It is rare for someone to start feeling symptoms again, however it can reemerge occasionally.

The best way to avoid a dangerous reemergence of mononucleosis during adulthood is to avoid the disease altogether. It is difficult to conceptualize all of the microscopic events taking place inside your body everyday, but just try to remember this article when you share your next soda!

Evelyn • Dec 31, 2023 at 8:29 am

As a child we get a big cold then our throat hurt we sneeze and everyone gets it in the home.