Wake Forest’s campus was nearly deserted at 8 a.m. last Saturday morning, with one exception: a long procession of students was shuffling into the Wake Forest University School of Law to face an approximately three-hour trial with the power to make or break all of their hopes and dreams. They came to take the Law School Admission Test, also known as the LSAT.

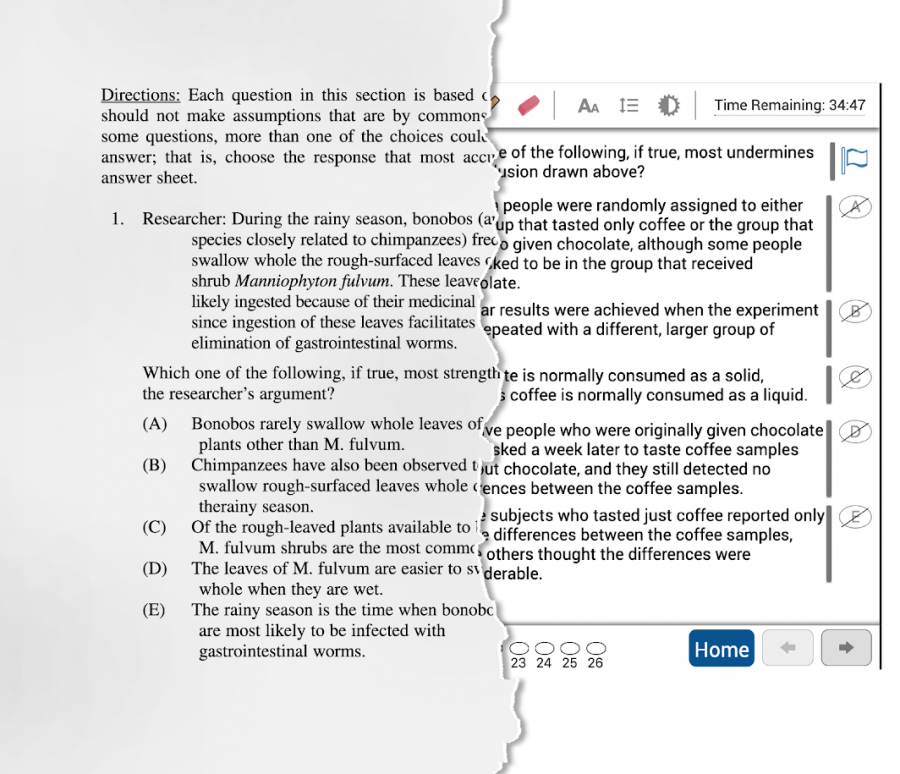

This was no ordinary day of standardized testing. These students were among the second group of law school candidates that had been subjected to the most drastic change the exam had undergone in over 25 years. Once a pencil-and-paper affair, the test has now been completely converted to a digital format: on a tablet, complete with a stylus.

“It’s important to note that the content of the exam is not changing a lick,” said Jeff Thomas, executive director of admissions programs for Kaplan Test Prep. “The content is the same, the length of the test is the same, the number of questions is the same and the scoring methods are the same. Students don’t have to learn different skills than they used to when preparing for the LSAT.”

Thomas clarified that many ubiquitous standardized admissions tests, such as the Medical College Admissions Test (MCAT) and the Graduate Records Examinations (GRE), transitioned to a digital format years before the LSAT. He cited a number of benefits from digitization, including greater efficiency, a greater number of testing days and a shorter wait for scores. However, the LSAT requires more physical engagement with its material, such as highlighting. Because of this challenge, the Law School Admission Council, also known as LSAC, had been working on the transition for over five years before finally going forward with it.

According to Russell Shafer, senior communications manager at Kaplan Test Prep, ample material was provided to help students adjust to the new format. This includes multiple digital practice tests on the LSAC website and an e-book put together by Kaplan.

The first administration of the LSAT’s new form was on July 15, 2019. Those who took the exam on this date did not know if they would be using the new format; approximately half received the digital test and the other half received a traditional one with a pencil and paper. Thomas said that a good number of students made their thoughts on the change heard.

“We’ve asked all of the students who have sat through the digital tests both in July and September to give us feedback on the experience and let us know if there are any unanticipated challenges,” he said. “The majority of our students have cited that they approve of the new format and it was easier to utilize than they anticipated, which is great.”

Seventeen percent of students to use the digital format rated their experience as “very good,” while 36% rated it as “good.” Thomas clarified that some students had responded that they preferred using paper and a pencil to complete exams, and that others had struggled to use the stylus.

“At first, I was not happy about it being digital just because I learn better on paper,” said senior Dylan Dobson. “But actually once I started practicing on a digital format it became a lot quicker and more efficient, so I actually like it a lot more now.”

Dobson has taken the LSAT in both formats since the change was first implemented. She said that the differing formats did little to affect her experience taking the test. She also expressed strong enthusiasm for the stylus, an instrument that was dually effective as a ball-point pen, which she was allowed to keep. Not every student was this enthusiastic, however.

“I would prefer to take it on paper,” said senior Ren Schmitt, who took the exam on Saturday. “The digital had some upsides, primarily the timer in the corner of the screen and not having to bubble answers on a scantron, but I find reading on screens to be more taxing than reading on paper.”

Schmitt also said that he felt the stylus could have been easier to use. However, he also said that despite his preference, he felt that the impact on his score was negligible. He also said that he made sure to take advantage of the provided preparation materials. However, despite the care taken by the test-makers to maximize success for all involved, technology has not proven infallible.

“The computer crashed right before we started, [on Saturday]” said Dobson, “so we couldn’t even start the test until everyone re-registered their tablets into the system. It was stressful, although it ended up being a pretty quick delay, only 20 to 30 minutes.”

Thomas said that LSAC was unlikely to make any more immense changes to the test in the near future, but that tweaks to the format would be implemented as technology improves.