On a breezy autumn evening, students filed into Wait Chapel to attend a talk by visiting guest speaker Kwame Anthony Appiah. The event began with an introduction from Professor James Otteson, director of the Eudaimonia Institute, the organization that co-sponsored the event with the Office of the President.

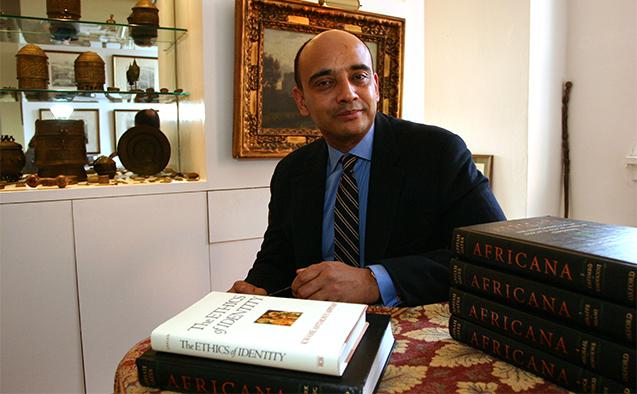

Appiah is the third speaker in the institute’s Noesis Lecture Series and is part of the Voices of Our Time Series established in 2006 by President Nathan Hatch. Hatch was the next speaker at the event, introducing Appiah to the crowd, listing his numerous accomplishments and accolades that include a National Humanities Medal from the White House and his recent book, The Lies that Bind — Rethinking Identity.

Appiah began his discussion on diversity by discussing his own diverse background: his mother was English, while his father was Ghanaian.

“I wanted to explore the ways narratives like these shape our sense of who we are,” he said.

Appiah described how he had desired to think about the differing categories that assist in shaping identity. He pointed to three distinct commonalities. He first asserted that identities come with labels, ideas about why and to whom they should be applied.

Appiah goes into further detail in his book about identity having five components: class, race, religion, culture and country. He said that none of them consistently take precedence over the other.

“All of them become salient in different circumstances,” Appiah said. He pointed to a historic example of religion taking precedence in identity in Northern Ireland in the 1960’s, in which one’s identity as Catholic or Protestant played an intrinsic role in the civil conflict.

Appiah went on to state that identity shapes an individual’s thoughts and behaviors, before describing how it affects the way people treat each other. He said that hierarchies of respect and power structures are “programmed” into people from a young age by society to form generalizations about society and the ways in which groups of people function within it. He said many of the cognitive processes surrounding identity had evolutionary benefits, as prehistoric humans needed to be easily triggered to take up arms against other groups.

Appiah then turned his focus toward America specifically. Although he was born and raised abroad, his studies soon took him to the United States; he has since become an American citizen. Appiah asserted that the political polarization of America is a function of the racial inequity that has afflicted the nation since its origin — which he referred to as America’s “original sin.” He asserted that ethics is also intrinsically linked to these ideas about race and identity.

“Identity precedes ideology,” he said.

Appiah explained possible solutions for solving identity schisms by describing a phenomenon known as the “contact hypothesis” by Gordon Allport: intergroup contact under a specifiable list of the right conditions can reduce prejudice. Appiah asserted that people cannot make progress unless they share thoughts on what they disagree and agree about. He said that this process is delicate, and difficult to map out with theory.

“I am a philosopher. I like theory,” he said. “But theory isn’t the only thing that matters.”

Appiah closed his talk by asserting that this evolutionarily-rooted tribalism is undermining American democracy. He stressed that the aforementioned identity labels belong to all communities, not just the repressed ones.

“We must try to make our views work for everybody,” he said.