Congratulations Wake Forest, you understand it. But your parents might not, and they might not even want to.

For a campus that is conservative relative to other colleges and universities in the United States, there is still a clear consensus at Wake Forest: climate change is real and it’s happening.

“I’ve been here for 10 years,” said Chief Sustainability Officer Deedee Johnston, “and in those years not a single student has ever told me they don’t believe that our climate is changing.”

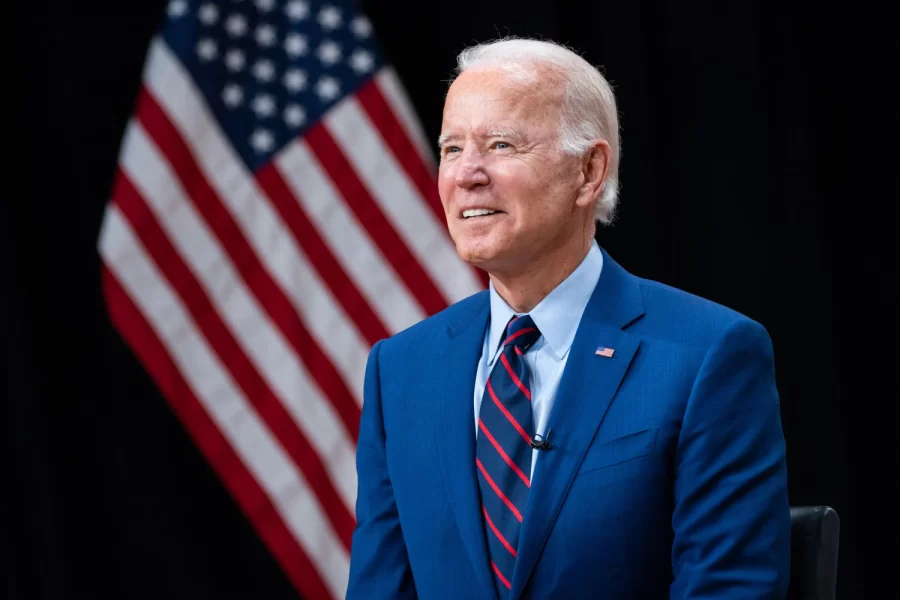

While young, educated students and faculty on college campuses have proven to be some of the strongest acknowledgers of the presence and severity of climate change, the United States still lags behind the rest of the world in coming to terms with the reality of climate change. A Yale University study on “Climate Change and the American Mind” revealed that 14% of Americans don’t believe in climate change and one in four don’t believe that human actions are having drastic effects.

Climate change denialism clearly still pervades factions of American political thought. Whether or not the intensely fortified roots of this belief can be quashed could be a determining factor in the world’s success in fighting off the damage humans have already caused, many environmentalists argue.

“Your politics are what predicts your accepting of science, which of course shouldn’t make any sense, but perfectly makes sense when you look at the psychology of it,” said Adrian Bardon, a professor of philosophy. “If people know that their group, where they’re from, their community or their political party needs to insist that it’s not true, they’re going to go along with it.”

The tribalism of climate change denial that Bardon explored may not be felt on Wake Forest’s campus, but is a reality in many of the communities from which its students come.

Particularly in communities whose livelihoods depend on the use of the land, water and their resources, the acknowledgement of climate change and the subsequent actions taken to address it would mean a temporary collapse of their way of life.

“The last time I was in church back home the preacher said that climate change was an aspect of the liberal agenda to get people to pay more tax dollars,” said sophomore Reece Adams. “I grew up in a small town in North Carolina where a lot of people work for oil companies, and they don’t want to believe in climate change because of what it means for their jobs.”

However, students who have grown up with an environmentally conscious education claim that even in their young lives there have been palpable changes which motivate them to take action.

“I grew up in the suburbs of Boston, which is a pretty clean city,” said sophomore Amanda Mosher, “but in the past 10 years you can sense the worsening of the air quality, especially when you go from the city to the suburbs. And in the news, climate change is everywhere if you look for it. How could seeing rainforests on fire and ice caps shrinking not make you want to take a stand>”

Evolutionary psychologists suggest that one of the largest contributors to denialism is humans’ innate fear of mortality. As humans gain an increasing understanding of the world around them, the reality of their own demise leads them to cling to ideas that insist that everything will be okay.

“One of the biggest conclusions of the research into climate change denialism is that it’s not a literacy problem,” Bardon said. “With regard to climate science as a conservative, the higher level of your literacy, the more likely you are to be engaging in denial. There comes a point when the amount of education someone has stops making a difference.”

Bardon, frustrated by a sense of impending doom, mentioned that it’s nearly impossible to re-educate people on an issue they feel they understand. There are then really only two options: make environmental concerns a main focus of youth education throughout America, or wait until the crisis forces people to feel the immediate effects firsthand.

Unfortunately for the environment, the severity of the crisis coupled with the psychological need for drastic effects to be seen before action is taken could mean that the world’s climate will reach the point-of-no-return with regards to what has been deemed normal throughout its existence.

“The problem isn’t that humans don’t understand the science, it’s that they don’t want to,” concluded Bardon.