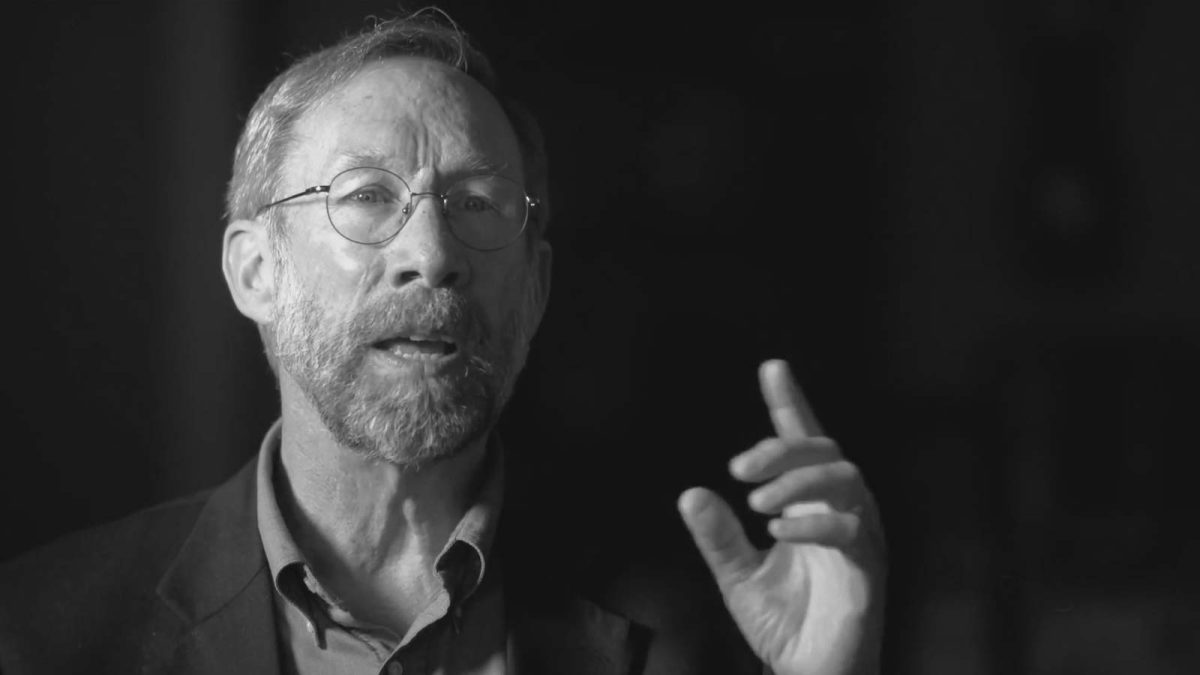

Sarah McDonald Esstman has a Ph.D. in microbiology and immunity from Vanderbilt University Medical School and a B.S. in biology from Florida State University. Her academic interest in biology centers around rotavirus replication and evolution, which has led her to run a virology research lab and become an associate professor of biology at Wake Forest University.

Why did you become interested in researching rotaviruses?

When I started my Ph.D. program at Vanderbilt, I was intent on becoming a cancer biologist and I learned during my cancer biology classes that some viruses cause cancer. So, I took a rotation working in a biology lab to learn a little bit more and just kind of fell in love with viruses. The virology lab I happened to work in was with a lab that was studying coronaviruses, which at the time, were common causes of the common cold and mild upper respiratory infections, nothing major. I ended up joining that lab and did my Ph.D. dissertation research on coronaviruses.

During that time span was when the OG SARS happened — Sars-Cov-1. We were shocked, you know, we’re like, ‘Oh my gosh, it’s a coronavirus. That’s crazy.’ For me, it really underscored the importance of basic biology research on viruses.

I was very interested in the virus that still caused a lot of disease in humans, but was not as well studied as coronaviruses. Rotaviruses cause severe diarrhea and vomiting in kids. When I started my rotavirus research, it was estimated that half a million kids each year were dying from rotavirus infections.

We’re all pretty aware of numbers now. We know that we’re hitting upwards of almost a million deaths from this coronavirus, but you can imagine rotavirus was killing half a million kids every single year for decades. It was like the most life-threatening virus that no one had ever heard of. That’s why I started studying rotaviruses and that’s what my lab works on still to this day. I have an active research lab at Wake Downtown and we have federal grants to answer basic questions about rotavirus.

How does the COVID pandemic compare to the rotavirus problem?

I think what we’re experiencing with coronavirus is above and beyond what, you know, is the worst pandemic that we’ve experienced in modern history.

Rotaviruses are endemic pathogens, meaning that it wasn’t like they came out of nowhere. You know, they came out of a bat and spread throughout the world, so it has just kind of been around for as long as we can remember.

This coronavirus pandemic is really novel in not only the rate of spread, but also the disparity of disease and the pathogenesis in different people. Some people don’t experience hardly any disease at all and then some experience really severe life-threatening disease. What it really helped me understand is we really need to be prepared for anything related to viral families.

This pandemic also is one that reminds me of how important it is for all different types of fields to work together. Because as fast as the scientists are trying to work to develop vaccines and antiviral drugs, there needs to be a lot of help with public health epidemiologists to understand and help at least convince us that these infection control measures are really important. There are ways to mitigate the spread without antiviral drugs — and those are the things that we’re asking everyone to do, which is wear face coverings, wash their hands and stay six feet apart.

What do you think is the likelihood that COVID-19 could spread throughout our campus via multiple clusters?

I think that it’s going to really depend upon the students.

I very much trust that the faculty members are taking it really seriously. A lot of the faculty members kind of represent a more vulnerable population than students as far as the severity of disease, so I think we’re a little bit more scared.

How it spreads is probably going to be a reflection of how seriously students take the precautions in their social time. I don’t think classroom spread is going to be a big deal, but I do worry. The recent closures of some of our neighboring universities here in North Carolina suggest that spread is really going to be driven by undergrads interacting with each other in social contexts.

I totally empathize with where students are. You know, you’re in college, you want to go to parties, you want to be able to meet up with your friends and you want to have dinner together. But my fear is that if students don’t stop those behaviors, we’re going to have enough positive cases that the university will be forced to close.

How do you plan to conduct your classes and engage students during this difficult time?

My classes will be fully online. My decision for that wasn’t necessarily driven by infection control measures, because I think that classrooms represent a very low risk transmission scenario. That said, I have three kids, and it wasn’t clear if they were going back to school at all. A lot of my decisions were driven by the practicality of having to be home on a lot of days with my kids and then also this idea of ‘if we do need to pivot online or if I get sick, what is the easiest kind of course of action?’ For me, it was to develop a fully online class, for all of those reasons.

As far as maintaining interactions, my class will as much as possible be offered synchronously. All of the same principles that I hold near and dear such as being a really good educator, as far as connecting with students, making sure that they understand the material and crafting out a lot of time to have one-on-one meetings with students as needed, is really what I hope to do.

Is there anything that you are looking forward to this fall?

I like interacting with students, even if it’s virtually. So, one of the things that I’m kind of excited about is that moving my class online has opened up a lot of seats in my biology course. It’s the largest class I’ve ever taught at Wake Forest, but I’m excited that I’m going to have the opportunity to reach more students.

I’m also hopeful that we can all pull together. I think we’re all leaning on each other a lot. I think we’re all giving each other a level of grace and flexibility that sometimes we previously didn’t. So, I think we can see each other in different lights.