If you didn’t believe in their commitment when Rube Foster founded the Negro League in 1920 to showcase the skills of African American baseball players barred from Major League Baseball; If you didn’t believe in their commitment when Bill Russel and his teammates boycotted their game after being refused service at a restaurant in Kentucky; If you didn’t believe in their commitment when John Carlos and Tommie Smith dropped their heads and raised their hands, adorned with black gloves, as they stood upon the podium during the 1968 Olympics; If you didn’t believe in their commitment when Maya Moore — one of the best female basketball players ever — stepped away from the game to devote her time towards freeing Johnathon Irons, an African American man who sat in a cell for over 20 years for a crime he did not commit; If you didn’t believe in their commitment when NFL quarterback Colin Kaepernick ignored the threat of being blackballed, sacrificed his livelihood and took a knee.

If you didn’t believe in the commitment of professional athletes towards using their skills, their voices and their platforms to promote what they believe in after last Wednesday’s walk-outs, last Thursday’s walk-outs and last Friday’s walk outs, then what exactly will it take to prove that for Black athletes and Black America, true equality has yet to be achieved?

Until it is, you can believe that no Black athlete and no Black American will be content to ‘shut up and dribble.’

When the NBA began to contemplate a return to play in late June and early July, players like Brooklyn Nets star Kyrie Irving voiced their concern with doing so. To continue the season at such a time, Irving contended, would distract from what was truly important — from what really mattered, beyond the court.

The league took Irving’s voice, alongside that of so many other players, coaches and activists, into consideration. When it was ultimately decided that the game would return, and that the platform would be used to promote social campaigns, some worried that the league wasn’t doing enough and that the games would overshadow the movement.

On Aug. 26, when players from the Milwaukee Bucks refused to take the court minutes before the scheduled tip-time in their playoff matchup against the Orlando Magic in protest of the shooting of Jacob Blake, those worries were quelled. The decision on behalf of those Bucks players showed the world precisely where the priorities of the Black athlete lie.

Three days prior and a thousand miles north, Blake had been shot by a police officer in the back seven times. His three children watched from the backseat of the SUV he was leaning into.

Wednesday’s walkouts prove, beyond any reasonable doubt, that the role of the athlete to enact social change, and to change the context of sports within American culture as a whole, has never been greater; and, the timing could not be more uncanny — four years to the day that Colin Kaepernick first took a knee, and on the third day of the Republican National Convention.

From atop the Olympic podium, John Carlos and Tommie Smith raise their fists in a human rights salute (Photo Credit: AFP/Getty Images)

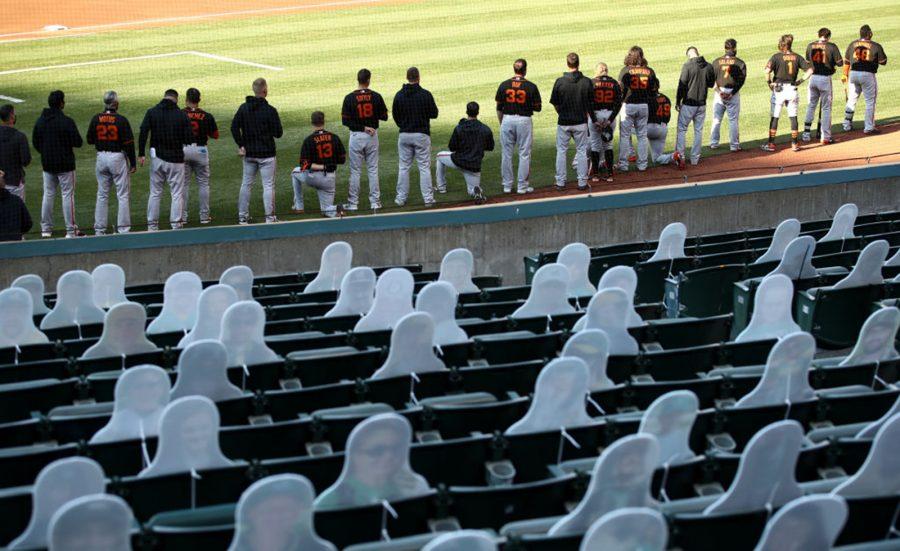

There were no basketball games played on Thursday, nor Friday. Players from the WNBA, the World Tennis Association, the NHL and the MLB alike stood in solidarity with the Milwaukee Bucks and the African American population when they decided to postpone their own games during days that followed. Among the most moving of the demonstrations was that which took place before the first pitch of the game between the Mets and Marlins on the 27. Players from both clubs walked out of their dugout, removed their caps and stood in silence for 42 seconds — a tribute to the legendary trailblazer Jackie Robinson. The players raised their caps in solidarity before returning to their respective clubhouses. The only thing that remained on the field, a Black Lives Matter shirt draped over home-plate.

“We are scared as Black people in America,” said Lebron James, who has long served as a leading figure among those athletes pushing for racial justice and social reform. Celtics forward Jaylen Brown echoed James’ sentiment, asking, “Are we not human beings? Is Jacob Blake not a human being? He deserved to be treated like a human being.”

Just as it was near the end of June, today our nation remains in flux. Several months ago, we were grappling with the combination of containing a pandemic — which was becoming more disastrous by the day — alongside the general upheaval — sparked by the murder of George Floyd in late May — that incited a series of protests and some riots across the country. Those protests, which took place in almost 550 different sites across America, included between 15 and 26 million demonstrators.

Fast forward several months, and things have changed slightly. But not for the better. New confirmed COVID-cases today are almost double what they were in early June, and Black Americans are still being shot by police officers. Does this mean that the protests and the kneeling and the walk-outs of athletes and activists aren’t working? That the jerseys draped with slogans calling for change or the creation of coalitions to promote diversity are fruitless labors?

It means that there’s still work to be done. That there are conversations to be had and things to be learned. It means that the fight for racial justice, the same fight that athletes have been aligning themselves with for decades, is far from over.