On Feb. 24, the United States Supreme Court (SCOTUS) is scheduled to hear an argument in favor of postponing the enactment of the Environmental Protection Agency’s Good Neighbor plan while it undergoes a challenge in legality in a lower court.

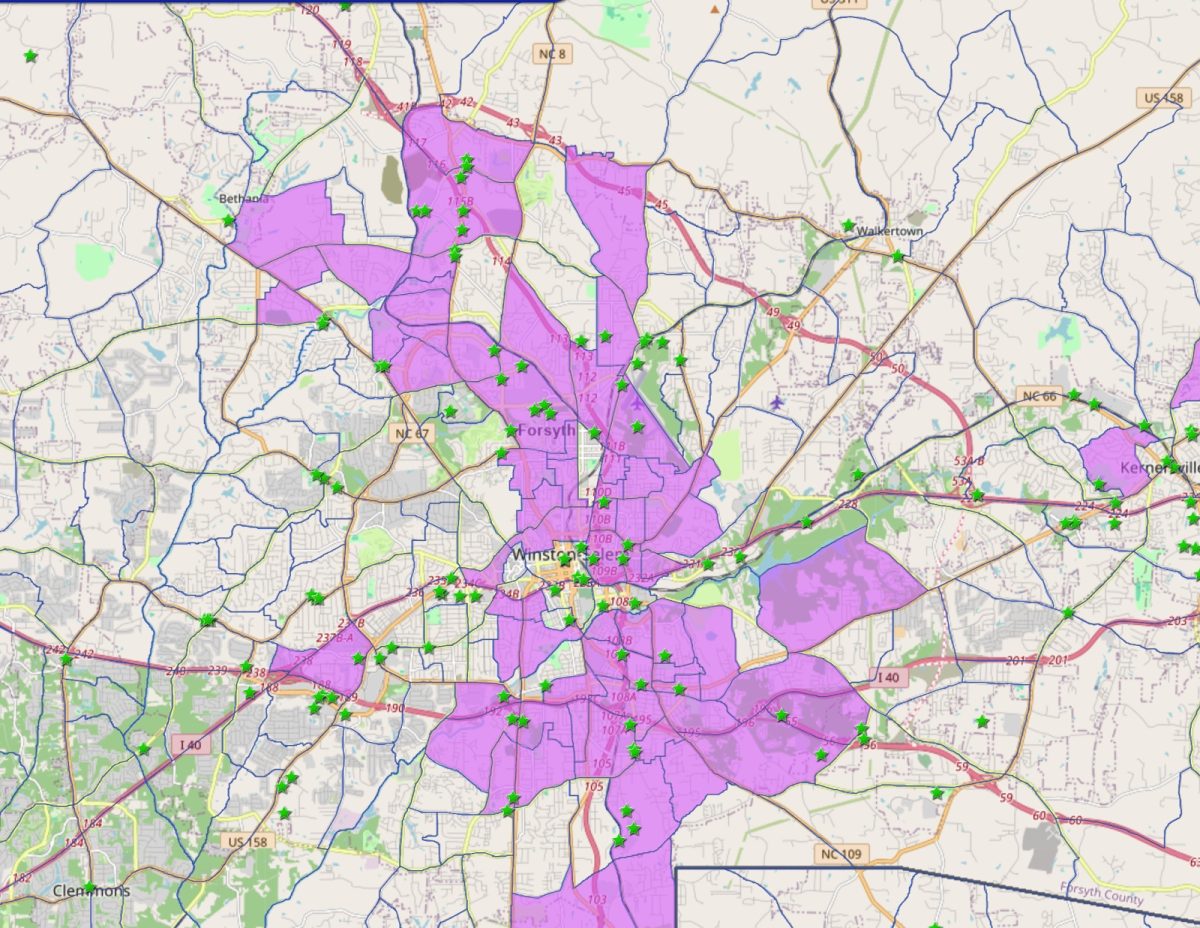

The plan was initially enacted on March 15, 2023 to significantly reduce cross-state nitrogen oxide pollution deriving from power plants and industrial facilities. The plan’s enactment would require 23 states to ensure that their emissions do not interfere with the ability of other states to meet federal air quality standards and is projected to decrease emission rates across the country.

What is interstate pollution?

Interstate pollution occurs when pollutants from upwind states cross state lines, thereby impacting air quality in downwind states. Exposure to nitrogen oxide pollution, in particular, has costly health impacts, as it can cause damage to the human respiratory tract and increase susceptibility to asthma and lung disease. According to the EPA, these health impacts are especially prevalent in low-income and minority communities, which are more vulnerable to these risks due to lack of access to health insurance and often closer proximity to the source of pollution due to the impacts of environmental injustice.

Nitrogen oxide’s effects are also harmful to the environment, particularly to vegetation and crop yields.

Federal air quality standards stem from the Clean Air Act, which requires the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to assign primary responsibility to states to ensure compliance with air quality standards. A federal plan helping states adhere to these guidelines has been in the works for decades, but increased interstate air pollution has exacerbated the severity of this issue — leading to the creation of the Good Neighbor plan.

Legal implications

Scott Schang is a professor of practice and expert on environmental law and governance at Wake Forest University’s School of Law. He provided insight into the significance of the challenges against the plan.

“The Good Neighbor plan is one of the most interesting ones in environmental law because it’s been decades in the making,” Schang said. “It’s gone across several different presidential administrations, all trying to tackle the problem of what you do when one state’s inability to comply with the Clean Air Act is caused by emissions from another state.”

He continued: “In some ways, it’s the paramount job of the federal government because it’s a problem created in one state by another state — which is exactly when the federal government should step in because they are supposed to help mediate these states.”

Challenges to the plan are primarily coming from pipeline operators and major coal-producing areas. West Virginia, Ohio and Indiana have all claimed that the EPA’s Good Neighbor plan is unreasonable and too costly, ultimately leading them to ask SCOTUS to block enforcement against natural gas pipeline engines while the plan is challenged in D.C. Circuit Court. This is where the notion of “federal overreach” becomes significant — this concept is often cited when states believe the federal government may be exerting its power inappropriately.

Dr. Stan Meiburg, executive director of The Andrew Sabin Family Center for Environment and Sustainability at Wake Forest, worked at the EPA for 39 years and served as the agency’s acting deputy administrator from 2014-2017.

“There are a host of complicated technical arguments around the rules,” Meiburg said. “How many different sources contribute to downwind air pollution, how much contribution is enough to be of concern, where the impacts occur, the cost-effectiveness of various control technologies and whether to allow emissions trading [are all considerations].”

Why are states insistent on not complying?

To understand state opposition, one must understand the risk-benefit analysis approach, which takes into account the risk-reward ratio of a given action. Schang explained how this applies to environmental regulatory processes and policymaking.

“By trying to regulate nitrogen oxide emissions and reducing them from your power plants and industrial facilities to benefit people to your east, you may see that as you bearing all the cost, but you’re getting none of the benefit,” Schang said regarding the considerations of upwind states.

With these states’ claims that Congress is granting the EPA too much power to develop its regulatory plan, the next question is: whose place is it to question the judgments made by technical experts on how to achieve environmental objectives?

“I think the EPA knows best on how to regulate environmental matters, not nine justices without any science degrees,” Schang said. “As long as Congress gives agencies sufficient guidance, then the court should defer to expert agency action provided the agency acted within the law.”

Schang continued: “Trying to regulate the environment using an administrative state in which Congress gives authority to an agency like the EPA to address issues doesn’t work if Congress has to make all the hard science decisions.”

What happens if the Good Neighbor plan is blocked?

If SCOTUS temporarily blocks enforcement of the Good Neighbor plan, it could severely impact the EPA’s goals regarding clean air and reduced use of coal, possibly affecting emissions targets — -which leads to the pivotal question: what are the possible implications and outcomes of challenges to the Good Neighbor plan?

Meiburg expressed his concerns about the lower court ruling regarding the plan’s future.

“The decision will turn on the court’s willingness to defer to the EPA’s technical expertise in making specific judgments about which sources should be required to put on additional controls or shut down, rather than any more fundamental legal or constitutional basis,” Meiburg said.