In February 2022, a fire ignited at the Weaver Fertilizer Plant, causing Wake Forest students and Winston-Salem residents within one mile to evacuate from the area. Two years later, the city is still feeling its effects.

The Weaver Fertilizer Plant sat next to underserved block groups in Winston-Salem –– which means majority-minority and low-income community members were the ones most affected by the evacuation.

While the plant never exploded, residents had to suddenly evacuate, without heavy assistance from the local government. In the weeks following the fire, $1 million was promised to the estimated 6,500 Winston-Salem community members who had to evacuate under the threat of the explosion. Two years later, only 656 families have been compensated.

“The reason it’s such an environmental justice issue is because 6,000 residents were displaced,” Crystal Dixon, associate professor of the practice for the School of Health and Exercise Science, said. “Most of them are families of color, particularly those experiencing poverty. You’re consistently seeing [that], every time there’s some kind of catastrophic environmental injustice, it’s always impacting low-income Black communities. And we know that’s related to redlining.”

Dixon is currently doing research into how the fire has contributed to environmental injustices impacting low-income communities, working with Wake Forest’s Department of Engineering and Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist. This work is done in conjunction with local partners, Neighbors for Better Neighborhoods and Iglesia Sin Fronteras.

The city of Winston-Salem appointed the local nonprofit Experiment in Self-Reliance (ESR) to distribute the promised funds to community members. The structure was payments of $200,000 in installments gifted to the non-profit, going up to $1 million as needed.

ESR has been working with Winston-Salem’s impoverished and homeless community since the 1960s when it was born out of former United States president Lyndon B. Johnson’s War on Poverty initiative.

Assistant City Manager Patrice Toney explained on a call why ESR was chosen.

“There was no formal bid process, only because there was this immediate need,” Toney said. “We went with a trusted nonprofit in the community … we also needed someone who understood how to work with low-income families.”

On Feb. 3, the Old Gold & Black attempted to attend the Weaver Fire Study Community Forum to talk to residents who were affected by the fire, but the event was closed to people outside the 2-mile radius of the plant. When the Old Gold & Black requested the list of residents who received compensation from the city, they were denied access and told the list was confidential due to its inclusion of contents such as residents’ addresses and income.

City funding didn’t reach all community members affected

According to the Weaver Relief Fund contract the city drew up for the ESR, the qualifying factor for reimbursement was that residents must be within a mile of the plant and impacted by the evacuation — such as having to find alternative food and shelter. If a resident could provide receipts of the expenses between Jan. 31 to Feb. 4 in 2022, they could be reimbursed up to $1,000, as needed. If receipts could not be provided, a resident could still be reimbursed $300. Citizens eligible for the fund had to make an appointment with the ESR or attend a singular event held at the Winston-Salem Fairgrounds in order to submit their application.

“They sent postcards to people within a one-mile radius,” Toney said when asked about community outreach. “We held just one event at the Fairgrounds that people lined up at. People who weren’t able to be seen at that event were invited to make an appointment at ESR. That’s why their location mattered going forward, for easy accessibility”

Director of Budget and Performance Management for Winston-Salem J. Scott Tesh explained some details surrounding the cost.

“My understanding is that [the ESR was] allowed to have access [to] up to 18% of the original cost [of $1 million] because they had startup costs associated with it,” Tesh said via phone call. “So basically, they were going to have enough litigation costs on the front end, whether they gave out $250,000 or $750,000.”

The final budget report for the Weaver relief fund shows that the city allocated $600,000 of the $1 million to the ESR to spend on impacted community members affected by the Weaver fire. Out of that money, around $241,000 was spent. ESR kept around $100,000 for administrative costs, which is about 41% of the $241,000 handed out to community members from the relief fund.

“From the city side, we had $1 million available for this — we didn’t spend nearly $1 million. We spent $341,000,” Tesh said.

The remaining amount, around $258,000, was given back to the city and retained in the city’s general fund — as the ESR was not able to distribute it to the impacted community members.

In a report from WFDD, it was stated that the ESR did not go door to door notifying residents of the Weaver fire relief fund — and one community member interviewed stated they had not received news of the money available. Despite not reaching a majority of the members in the community, the fund was closed on June 30, 2022.

On the phone, Mikalah Muhammad, the digital marketing and data analysis associate for the ESR, responded to whether the organization could have distributed the money if they had more time.

“I am going to say no because we ran all the way from February to June,” Muhammad said. “For the amount of people that lived in that area, I don’t think we could have gotten to more people. They had to come out on their own, and I believe a lot of the reason people didn’t come out was because you had to have receipts to be reimbursed as well.”

As mentioned earlier, residents who could not produce receipts still were eligible to receive funding up to $300.

Alongside residents facing financial burdens due to the evacuation, Winston-Salem has a disproportionate allocation of hazardous waste sites concentrated in the city’s majority-minority and low-income communities.

The overlap between hazardous sites and underserved blocks

In 2024, taking a step back to look back at the composition of Winston-Salem is crucial. When Highway 52 was constructed between 1948 and 1962, it segregated the majority Black community of East Winston from the more affluent, white community to the West. This highway cut off East Winston residents from the rest of the city and created some of the largest food deserts in the United States. Additionally, the city has been consistently ranked as one of the lowest in the country for upward economic mobility — ranking third worst in a 2015 Harvard University study.

In 1986, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) authorized the Emergency Planning and Community Right to Know Act (EPCRA). This act’s mission was to help communities plan for chemical emergencies like the Weaver fire. Under the EPCRA, companies must report to the federal, state and local governments about what chemicals and hazardous materials they are storing and utilizing.

After the fire, the city increased its monitoring of potentially hazardous sites. Since 2021, Winston-Salem has had to examine multiple buildings across the city that could be potentially harmful to the surrounding communities. The Weaver Fertilizer Plant failed to accurately report the amount of hazardous chemicals — in their case ammonium nitrate — stored in the facility.

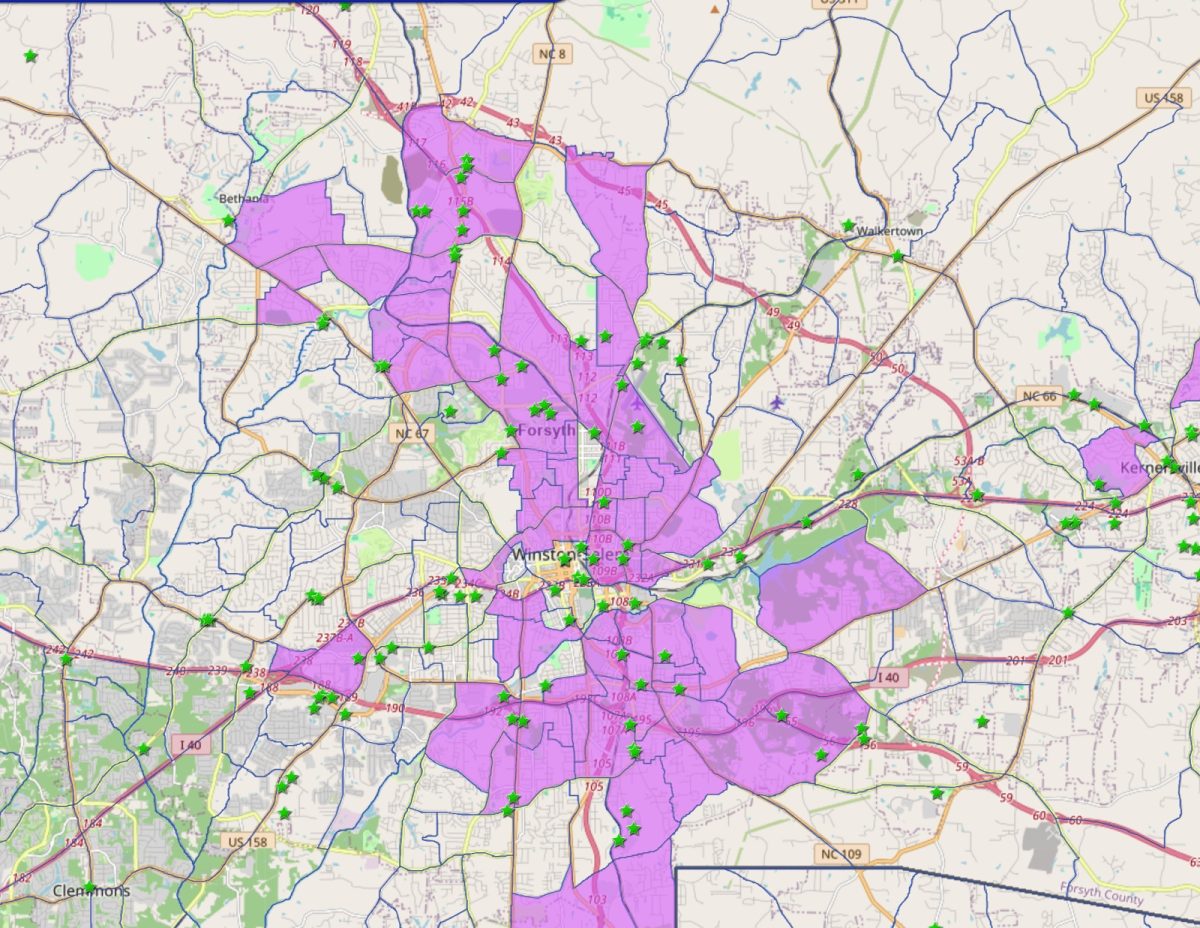

Most of these hazardous sites, like the Weaver Fertilizer Plant, sit in communities that are mainly composed of majority-minority and low-income residents.

Dixon believes that redlining and systematic, environmental racism play a big part in the structure of Winston-Salem.

“This consistent issue is happening in Winston-Salem and it’s always a conversation that’s never really particularly addressed — because it’s burdening Black and brown communities specifically,” Dixon said.

In a 2022 document, 31 addresses in Winston-Salem were listed as having to report to the EPCRA, two of which are owned by Wake Forest University. All of these sites listed contain hazardous materials that could have disastrous public health effects or threaten community safety –– like the 600 tons of ammonium nitrate stored in the Weaver Fertilizer Plant.

The North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality (NC DEQ) provides a tool called the Department’s Community Mapping System. This system can be used to magnify sites that contain environmentally hazardous materials that also impact community health while seeing where the facilities are in the racial and economic makeup of the city. As Winston-Salem remains redlined and racially divided, this source provides valuable insight.

According to the mapping system, these underserved block groups are mainly composed of communities that are majority-minority and low-income.

“When the Weaver Plant fire happened at Wake Forest, there was absolutely no conversation about staying on campus. They closed down and got out of the place.” Dixon said, “ But I always challenge the system and say, ‘Well, why don’t you respond that way for Black and brown communities when there [is] an exposure?’”

Correction: This article has been updated to more accurately reflect Crystal Dixon’s work with the Weaver Fire.