On Aug. 8th, 2023, the city of Lahaina on the island of Maui, Hawaii, erupted in flames. More than 2,500 acres were disintegrated in the blaze, including residential homes, temporary housing units, schools, roads, museums and most of the town’s primary infrastructure. Roughly 100 people were killed in what is now considered to be the deadliest fire in the past century of U.S. history. Thousands of residents have been displaced from destroyed homes in a state which already has the fifth-highest rate of homelessness compared to all other U.S. states and territories.

Although the fire was extinguished on Aug. 13, the road to recovery stretches far into the future of Lahaina’s residents. The U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) estimates it will cost roughly $5.52 billion to rebuild the infrastructure lost in the fires in a process likely to last many years.

Dr. David Wren, a professor of chemistry at Wake Forest, recalled when his hometown of Paradise, Calif., burned down as the result of a wildfire in 2018. He explained how the consequences of these disasters can last for years.

“Following the immediate shock of the event, a lot of people don’t understand the scale of the recovery that follows, as in how long it truly takes to rebuild in the aftermath of a fire like that,” Wren said. “My high school only just reopened this year. And [Paradise is] lucky, because my town is on the mainland. For an island like Maui being further from resources, it could take much longer.”

Weather and climate disasters have significantly increased in the past 50 years, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA). However, the data points toward climate change as the primary culprit for the recent spike in meteorological tragedies, wildfires like the one in Maui cannot be solely attributed to climate-related weather irregularities. In fact, centuries of extractive agriculture practices in Lahaina’s sugarcane and pineapple industries have depleted the fertility of the island’s soils — making the land much more fire-prone.

While the cause of the fire has not been officially stated by authorities, there is much speculation. Some believe it is due to climate change and the dryer conditions in Maui. Others, however, claim that downed power lines started the flames. Hawaiian Electric has adamantly denied these claims.

Stephen Smith, professor of environmental science at Wake Forest, said that in Maui, climate change may have exacerbated the risks associated with an already environmentally degraded landscape.

“While climate change is not the single perpetrator of the Maui wildfires, the drought that the island experienced this year can be attributed to rising global surface temperatures causing weather extremes,” Smith said. “And it was the combination of drought conditions and really high winds that made the wildfires in Maui so devastating.”

Hawaii’s economy is heavily reliant on tourism and real estate, with a housing market leading the highest prices for land and houses in the country. For many native Hawaiians, this means affordable housing is hard to come by and often found in places with poor environmental and human health conditions.

The housing inequity experienced by many native Hawaiians is an example of “climate gentrification,” a term describing increased difficulty for local people to afford housing in safer areas after a climate-amped disaster.

“Often, environmental inequities are most observable when you look at where marginalized communities live in contrast to affluent ones,” said Crystal Dixon, associate professor of the practice in the Department of Health and Exercise Science. In her research on environmental racism, she has found that communities of color are often disproportionately burdened with environmental health hazards through both policy and practice.

“In Maui, unfortunately, most of the native Hawaiians will likely not be able to return to the land that burned where their homes once stood,” Dixon said. “It’s just not going to be affordable when new urban development will cater toward making the most money.”

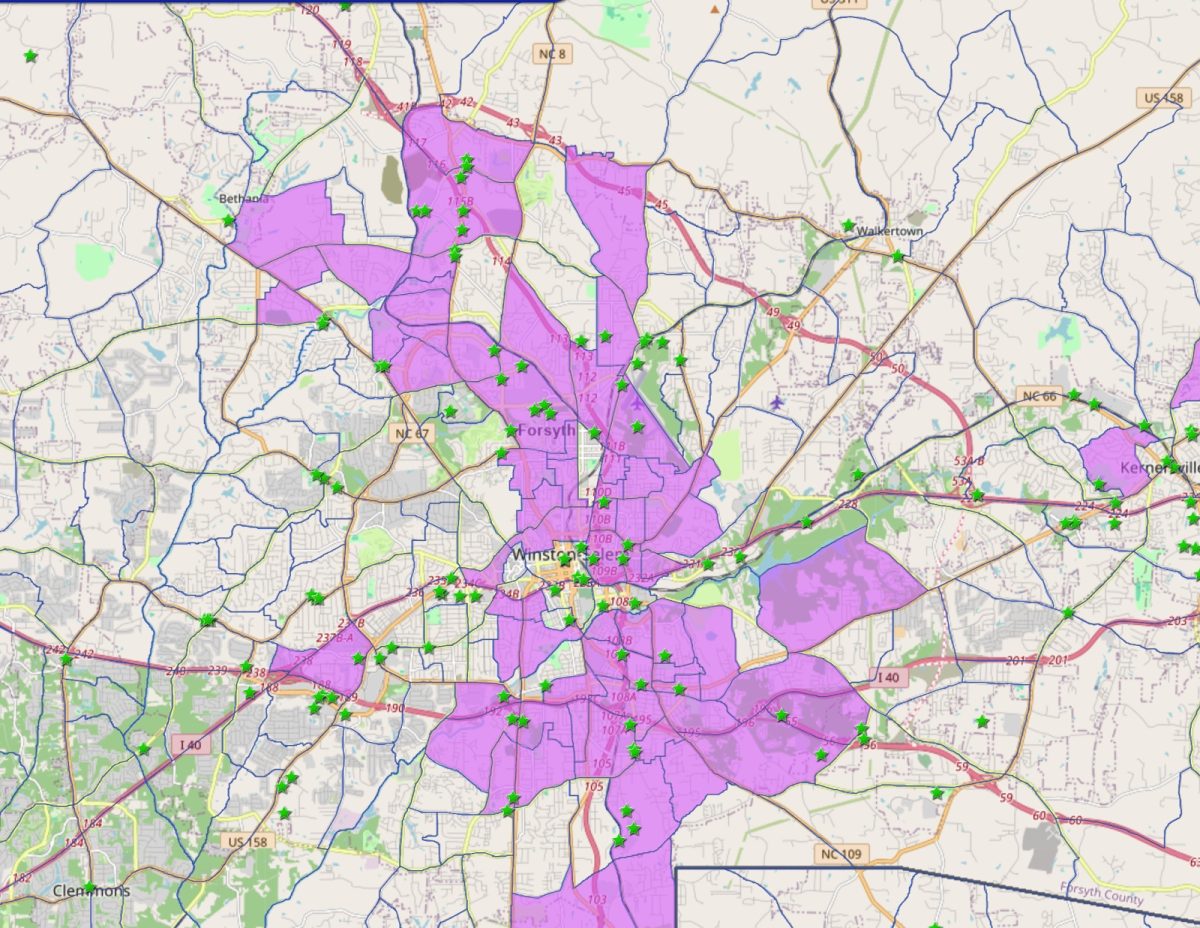

Instances of environmental inequity are observable in Winston-Salem’s very recent history, as well. In February 2022, a fire at the Weaver Fertilizer Plant erupted less than a mile away from roughly 6,500 residents, who were quickly urged to evacuate due to hazardous air quality conditions and the threat of explosion. The homes located in close proximity to the Weaver Fertilizer Plant are valued at significantly lower prices than other neighborhoods in Winston-Salem. These homes are affordable to those who work in lower-income jobs and are predominantly communities of color.

When interviewed in 2022 immediately after the fire at the Weaver Fertilizer Plant, Dixon noted that the placement of marginalized communities close to areas of high risk of environmental degradation or disaster is no coincidence.

“Since the 1930s, a practice called redlining has placed certain communities near toxic environmental conditions because the property values are lower, and they are cheaper places to live, but they are also really the only affordable places to live for under-resourced communities to live,” Dixon said. “In Maui, the same phenomenon is happening. The difference is, in addition to ecotourism and gentrification pushing up housing prices, the wildfires have dwindled what little housing was already available.”

Although Maui’s tragedy is geographically distant from Wake Forest’s campus, Dixon points out that insights can be drawn from the systemic issues of class, race and equity which affect our local communities as well.

Wren echoed Dixon’s perspective. As part of his curriculum, he devotes one class period each semester towards teaching the science of climate change.

“I realized that Wake Forest doesn’t have a formally required class about how climate change works, and I wanted to emphasize to students that what happened to me and my town could happen to anybody,” Wren said. “Students are also at an age where they can vote. I try to both educate and empower students. Voting for officials that have climate-forward policies, that will take environmental health risks into account; that’s something everybody can do to make a difference.”