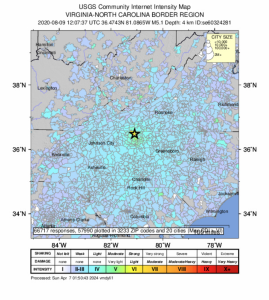

Following a magnitude 5.1 earthquake in Sparta, N.C. four years ago, the Appalachian region has seen a perceived rise in seismic activity.

The 2020 earthquake was the largest recorded earthquake in North Carolina in almost 100 years. The damage was severe, impacting roads and utility lines, and damaging the foundations of many homes. The N.C. General Assembly provided $24 million for post-earthquake recovery.

Since this event, several smaller earthquakes, including three this past June, have been reported in the region.

But are earthquakes in western North Carolina increasing on average? Should residents be concerned about a rise in seismic activity? According to Dr. Scott Marshall, a geophysicist and professor at Appalachian State University, the answer to both questions is largely no. However, the region is an interesting place in terms of seismic activity — with large-scale earthquakes tending to have longer-term impacts.

In the following interview, Dr. Marshall explains the cause of Sparta’s earthquake and the unique circumstances in this part of the state that have led to a perceived uptick in earthquakes.

—

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Breanna Laws: I want to talk about the Sparta earthquake a little bit. Could you describe it?

Scott Marshall: If I recall, I think it was on a Sunday morning. It was a magnitude 5.1. Typically, a magnitude-five earthquake is not going to cause that much damage, but this one did, and part of that is because it was very shallow.

With deeper earthquakes, you’re farther away from the source, so the waves sort of die out before they get to you. Shallower earthquakes are more dangerous, and this was on the very shallow end for earthquakes — the United States Geological Survey (USGS) has it at 4.1 kilometers, which is about two and a half miles.

In my reading about Appalachian earthquakes, I learned about a newly discovered fault line. Can you tell me how that was discovered and what that means for the region?

When the Sparta earthquake happened, a group went out and looked at where the fault had ruptured and cracked the ground, and they did some mapping.

I think the media quoted it as being a new fault, but the question is new to who? It’s new to society because nobody had ever mapped it before, but it’s certainly not to imply that a new crack just popped open and started having magnitude-five earthquakes. It was an existing crack.

How are these fault lines typically formed?

If you have a slab of any material and you pull the top and the bottom in different directions, the material is going to change shape, and it can only bend so much before it breaks. And they break by forming fractures. If they’re sliding on that fracture, we call it a fault — and faults are ubiquitous. You can’t go anywhere without finding a fault.

How are faults created in an area like Appalachia that isn’t technically on a plate boundary?

The Appalachians aren’t on a plate boundary now; however, when they were built, they were a major plate boundary. Africa ran into North America hundreds of millions of years ago, and when those two plates ran together, they crumpled and formed very tall mountains.

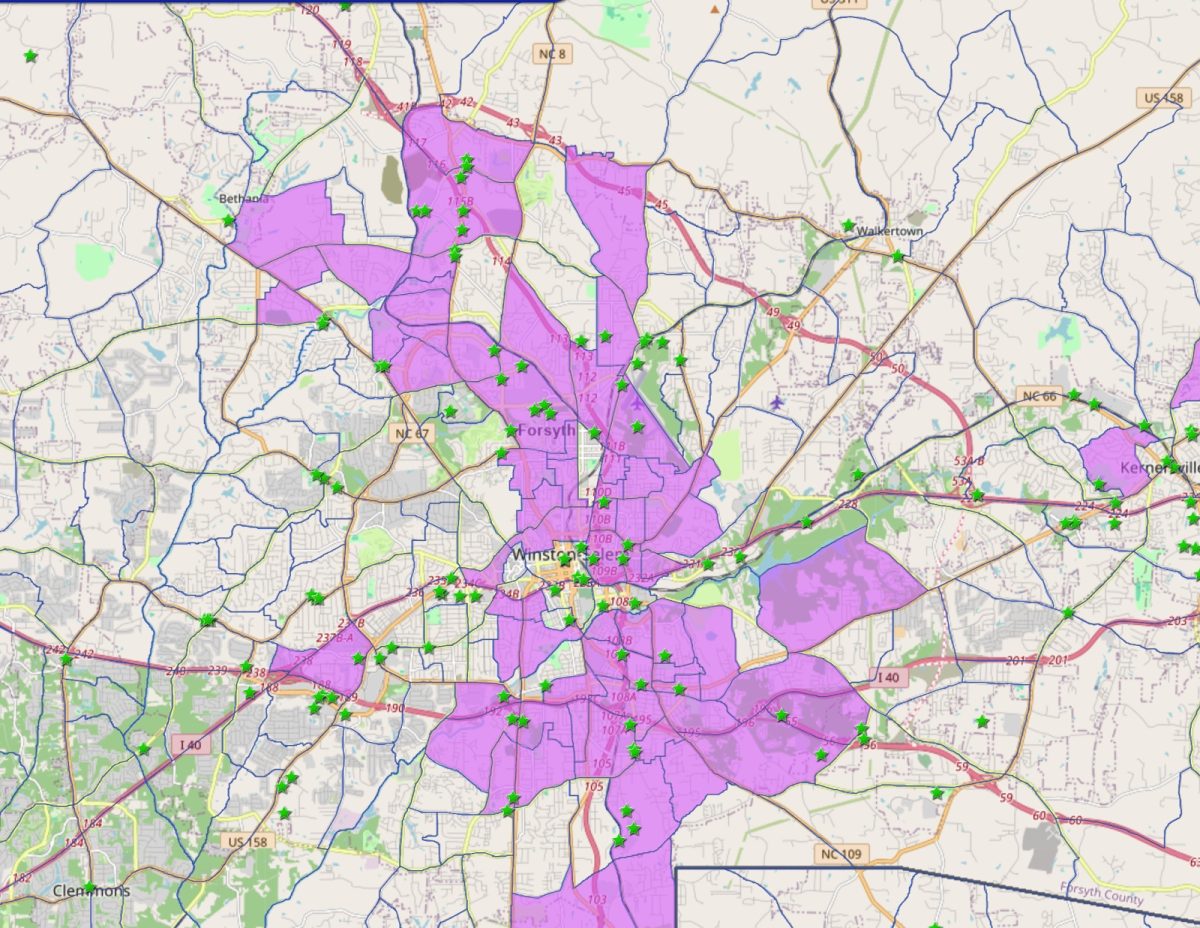

There are probably hundreds of thousands of faults in the Appalachians. They’re all left over from when the mountain ranges were formed, and some of them occasionally slip and produce earthquakes. We call these intraplate earthquakes because they’re within a plate, and they are notoriously difficult to study because we don’t get as many earthquakes.

Now, if I were to show you a map, you’d say ‘That’s a lot of earthquakes,’ but then if I show you California, you’d realize there are 100 to maybe 1000 times more earthquakes in that region. Seismometers are incredibly sensitive. There are probably millions of earthquakes that people never feel, but the instruments do.

I read that earthquakes in the Appalachian region are becoming more commonplace. Is that a trend you’ve noticed?

I have not noticed that trend. After the Sparta earthquake happened, I plotted all the earthquakes from that year and compared them to previous years, and they looked about the same.

The thing people forget about is the aftershocks. When you have a magnitude five, it’s going to create aftershocks. And people are going to say, ‘What’s going on? We didn’t used to have earthquakes all the time.’ But that earthquake in Sparta is still popping off aftershocks today, and the frustrating part of the eastern U.S. is the rate at which aftershocks decay with time.

The decay time is very fast at plate boundaries; If you have a magnitude five in California, its aftershocks are probably over in a month. But if you have a magnitude five in the eastern U.S., those aftershocks can continue for years.

There are still some different ideas about why that happens — earthquake science is definitely one of those areas where we don’t have all the answers. So being an earthquake scientist requires a sense of humility because we are still often surprised by new discoveries. This is what makes studying earthquakes fun.

Betty Laws • Sep 26, 2024 at 12:40 pm

A very good Story And gave us knowledge about earth quakes