Steven Spielberg’s drama The Post, which concerns the anxious days surrounding the publication of the Pentagon Papers nearly 50 years ago, is about as heart-thumpingly exhilarating as it gets for journalism nerds. But in addition to being an ode to the fourth estate, the film is hugely relevant today, as President Donald Trump’s antagonism towards the press strikingly resembles that of President Richard Nixon.

At the time, the government was trying its mightiest to prevent the press from getting the news out, and that concept is just uncomfortably familiar enough to make The Post a thoroughly 2018-centric film.

The Pentagon Papers, which were authorized by Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, comprised a top-secret report that recounted the scope — vastly greater than was publicly known at the time — of U.S. involvement in Southeast Asia during the Vietnam War. It detailed how five presidents, from President Harry Truman to Nixon, knew they were fighting an unwinnable war yet continued to escalate the conflict. The New York Times printed excerpts from the Pentagon Papers first but was accused of violating the Espionage Act and was stopped by a court injunction against further publication. Therefore, when The Washington Post acquired part of the Papers, its publisher and executive editor risked imprisonment for contempt of court — but they made the decision to publish them anyway.

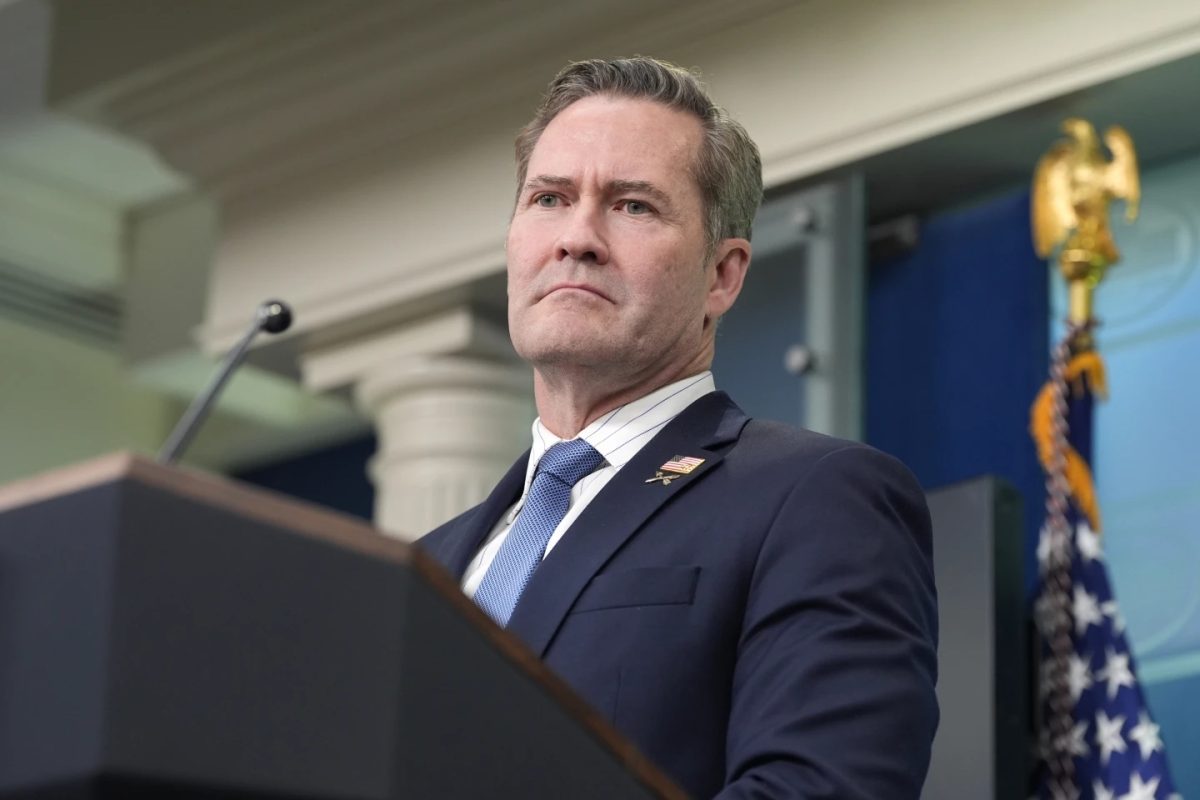

Thanks to The Washington Post, democracy survived the darkness. Change — eventually the demise of the Nixon administration — was coming, and it was the result of journalists’ hard work. But changing attitudes towards the press call into question whether a similar leak today would survive partisan efforts to discredit the messenger. President Trump’s many chilling comments about the press validate discrediting unwelcome news as “fake,” so would similar breaking-news coverage today change the minds of anyone not predisposed to believe it? Ben Bradlee, who oversaw not only the publication of the Pentagon Papers but also journalists Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein’s revelation of the Watergate scandal, was ardently committed to the role of the media as watchdog. But that role is threatened when a significant percentage of the public distrusts the media. President Trump has called the press “the enemy of the people” (a term straight out of Joseph Stalin’s playbook) and has commented that it is “frankly disgusting the way the press is able to write whatever they want to write” (not to mention his idiotic “Fake News Awards.”) Due to the continuing erosion of the press’ authority, if a revelation similar to the Pentagon Papers was published today, it’s likely that the problem at hand would be diminished by partisan hyper-skepticism about the credibility of the press. The Pentagon Papers marked an epic instance of the press speaking truth to power, and it’s troubling that a similar moment seems to be out of reach in the current climate.

Thus, the most important theme of The Post is the danger to the public if the White House doesn’t respect the freedom of the press. Daniel Ellsberg, the military analyst who first got the Pentagon Papers into the hands of The New York Times, at one point suggested that making an equivalence between reporting information that’s damaging to a particular president and treason was “very close to saying, ‘I am the State,’” quoting King Louis XIV’s declaration of absolute power. The Supreme Court ruling retains powerful relevance in 2018: “In the First Amendment, the Founding Fathers gave the free press the protection it must have to fulfill its essential role in our democracy. The press was to serve the governed, not the governors.”

That being said, because The Post avoids unequivocally exalting journalists, it’s a good reminder that even journalists with the best of intentions are imperfect humans. Katharine Graham, the publisher of The Washington Post, was cozy with McNamara and President Lyndon B. Johnson, and Bradlee was buddies with President John F. Kennedy. Over the course of the film, they slowly realize that their judgment in the past had likely been affected by their relationships with those in power. “We don’t always get it right. We’re not always perfect,” Graham said to Bradlee at the end of the film. “But I think if we can just keep on it, you know? That’s the job, isn’t it?” Hopefully, 50 years later, journalists will follow suit.