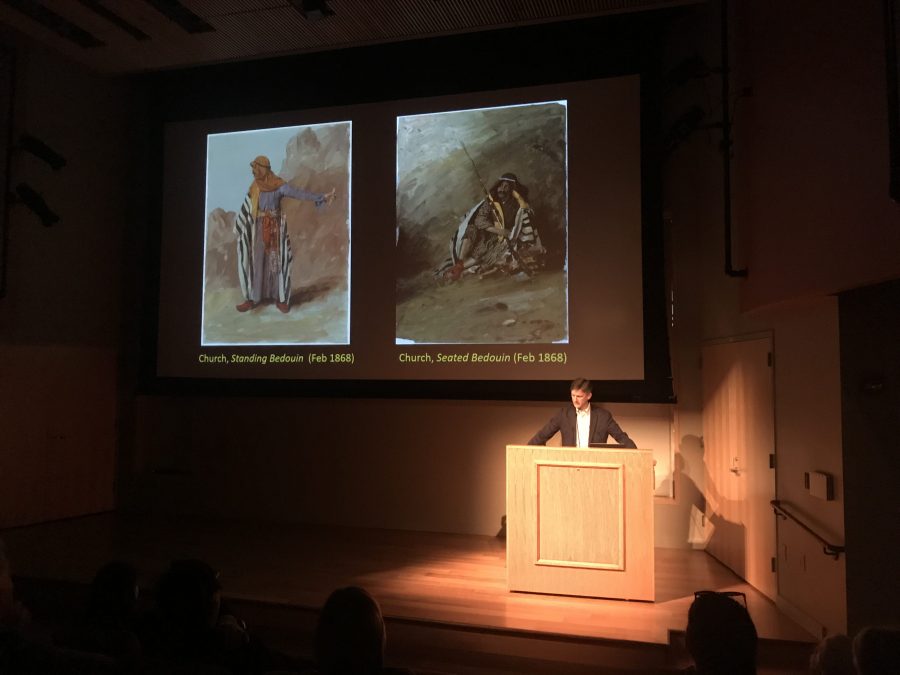

In tandem with the newest exhibition at Reynolda House Museum of American Art, History Professor Charles Wilkins gave a lecture entitled “Saints, Soap, and Second Thoughts: Palestine in the Era of Frederic Edwin Church.” With an active audience and new perspective, Wilkins worked to contextualize the paintings of Frederic Church within the time period of his artwork.

Termed “A Painter’s Pilgrimage,” the collection includes an array of works Church created during his time living in modern day Palestine with protestant missionary Daniel Bliss. His pieces depict vast mountain ranges, olive orchards and local individuals, among other pleasing landscapes.

To better understand the art, Wilkins started his lecture by stating that most individuals have an understanding of the Middle East today, but many do not know what Church experienced while exploring the region. By just viewing his work, one would receive an extremely “romanticized” and stereotypical view of the area.

“Well, I think any painter is a product of his or her environment, of his cultural formation and education and his interaction with other people,” Wilkins said. “So, I think to take into account the painter’s outlook and history is absolutely necessary. I think painters paint with great intention and great economy in general. But, that intentionality means that they are drawing on their own observations of the world. So, I think that history plays an essential role and the art historians I know are as much historians as they are people who look at art.”

One of Wilkins’ main points discussed the idea that many individuals were not as religiously divided as Church portrays them to be. In fact, he discussed how Jewish, Muslim and Christian sects all shared “local saints” who they appealed to for blessings and protection. According to Wilkins, this regional religion was spread through the oral culture of the society. While discussing this topic, he projected side-by-side images with Church’s art to point out clear misinterpretations and exaggerations in the artwork.

The second argument of the lecture was that Palestine did, in fact, have a productive economy. Church’s art continuously portrays a lackadaisical economy, such as a camel resting on the ground. Wilkins contradicted this by discussing the bustling economy of soap-making, agriculture and trade that defined the 19th century. With this idea, Wilkins solidified the argument that Church approached his paintings with a predisposed idea of how the Middle East functioned, both culturally and economically.

At the end of his lecture, Wilkins opened up the floor to questions about everything from tourism to a discussion of orientalism. He stated that his lecture should be viewed as “a compliment to the cultural baggage Americans take with them” to foreign places.

“I think that Reynolda House is a wonderful resource and the things that I can’t show [students] in the classroom, they can see in living color, in the texture, in the presentation and in the captioning,” Wilkins said. “It’s a much richer approach to the visual aspects of history.”