Monte Carlo is a place of glittering wealth and passion, a tiny quarter within the tiny principality of Monaco that attracts bursting bank accounts from all over Europe. It’s a vacation spot for the mega-wealthy, and is home to the Monte Carlo Casino — an establishment littered with various Bond-like critters in tuxes, scoured by strict floor men whose necks are so stiff they may well be made of china.

But Monte Carlo is also host and home to one of tennis’ premier events, the Monte-Carlo Masters 1000 tournament, where the best players from around the world compete in the coveted locale. It is fitting that such athletic largesse takes place in a spot of concentrated wealth. Every year I hope for the noblisse oblige to extend beyond the tennis court into the laymen of Monte Carlo, a town where most workers ferry in due to stratospheric real estate, but all that is guaranteed right now is a superb level of sport.

The Monte Carlo Masters marks the first big clay-court event of the year, a transition from the hardcourt warfare of Australia and Indian Wells.

High bounces and atom-splitting strokes soften into gentle, slower tactics as the Martian clay absorbs pace and plays it back with spin.

John Isner and other pace-predominate players prepare to struggle with the unforgiving surface and its indifferent absorption, while the Rafael Nadal’s and Feliciano Lopez’s of the world relish the shift from brutality to brush.

Nadal’s speed, paired with a slower pace of play, makes his gnat-ish tendencies all the more infuriating, yet all the more pleasureable to watch. Lopez’s slice-only backhand cuts through the court with the low-altitude clench of a puck on ice, perturbing the spectator as much as it wrong-foots his opponents.

Clay has perhaps the most personality of all the surfaces. It has the unique ability to take a shot you hit and pervert it into either something devastatingly unintended or woefully ineffectual. Players who are able to adjust to, or even relish, the opportunity for error are able to perform best. David Foster Wallace seems like he would have liked clay, since he was “a pretty untalented tennis player,” at “his very best in bad conditions.” Foster Wallace claims this is because of a “weird proclivity for intuitive math,” not any consummate athletic ability.

Clay is not an inherently “bad condition,” but it isn’t straightforward, either. Foster Wallace was talking about his brain-powered game in the context of the wind-whipped Midwest, not the skittish clay of Monte Carlo, but the same brainy mode of play applies.

The smartest players usually prevail, although it must be noted that the most exceptional case is Rafael Nadal, who does not so much outsmart his opponents on clay as much as he outraces them. In the case of Nadal, unconscionable speed, endurance and ungodly topspin propelled him to become the king of clay. He is the perfect player for the surface that slows, and he is in full bloom as the number-one seed in Monte Carlo.

The tournament should be exciting, since Marin Cilic, the 6’6 Croatian, is seeded second. His game is opposite Nadal’s, and runs on pure power. Cilic’s recent success rocketed him to a number-three world ranking (Federer, at number-two, is not competing in Monte Carlo), but his game rolling into the clay-court season is naturally at a disadvantage, since his monstrous serve will lose some of its power on clay.

It will be interesting to see who comes out onto the red-hot surface firing.

If it seems to be Nadal again, he will surely run away with Monte Carlo and possibly the French Open, which he has won ten times. But age is now a factor for the speedy Spaniard, and at 31, he has nearly run his body into disrepair.

That said, as one of the greatest players ever, I expect Nadal to perform with the passion and fearlessness of a player in his youth. Clay has been his best friend his entire career. It may be hard to pry the two apart.

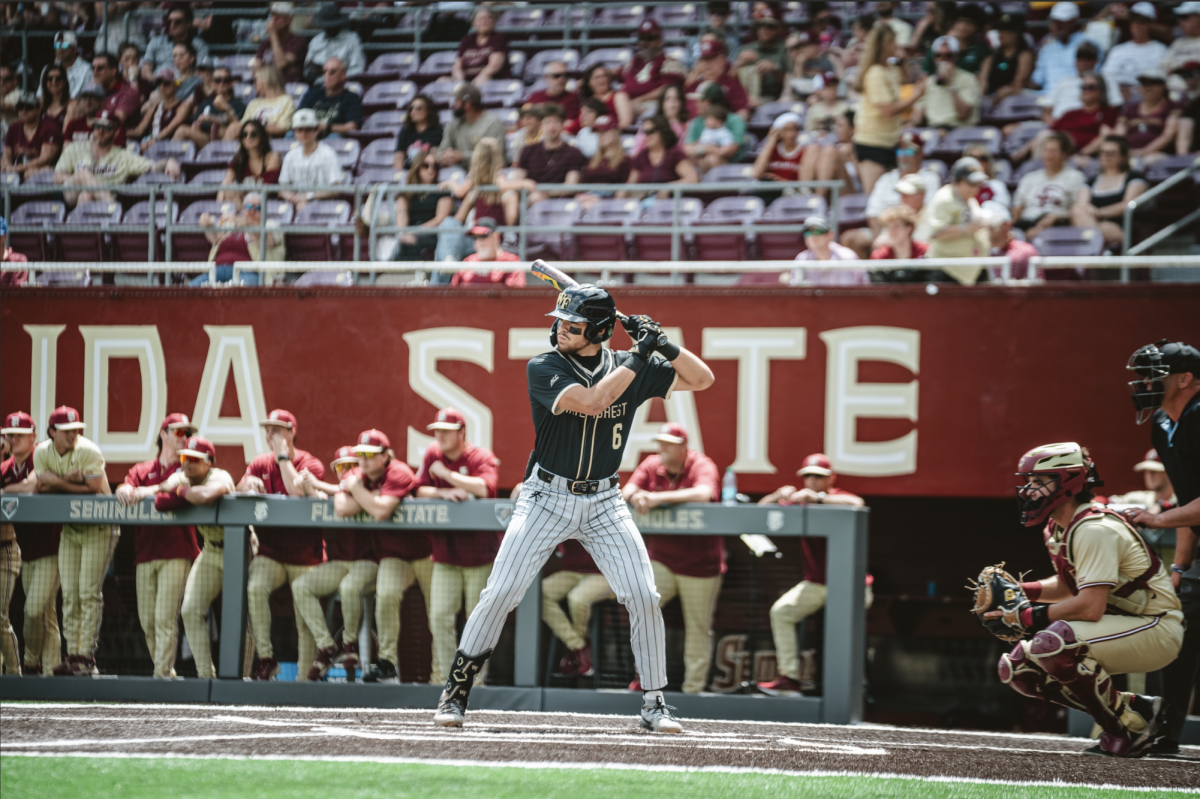

![“It's not necessary to win, but [it is necessary] to not give up,” freshman Charlie Robertson said of his team's culture.](https://wfuogb.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/7Q0A1456-1200x800.jpg)