In looking at what causes party culture, it becomes a question of the chicken and the egg: which came first?

At Wake Forest, where party culture reigns, many of the factors that feed this culture have long existed, such as a popular athletics program, a limited number of exciting social opportunities off-campus and an active Greek community.

But behind all this is another looming factor: affluence.

Nationally representative data shows that students attending high schools with high proportions of affluence are much more likely to report intoxication and the use of illicit drugs, according to a Washington Post article by psychology professor Suniya Luthar. If caught, these students usually get out of trouble and continue their behavior, which can lead to higher rates of substance abuse, as research suggests.

This data is relatively new, with the first findings having only been published in the late 1990s. Until that point, suburban affluence was never thought of as a risk factor for substance use and abuse.

Peter Rives, assistant director of Wellbeing – Alcohol and Substance Abuse Prevention, believes these findings are consistent with Wake Forest’s own experience regarding affluence and drinking.

“We admit fewer non-drinkers and fewer-low risk drinkers than our national comparison schools,” he said. “Then we admit more problematic drinkers and more heavy episodic drinkers than our comparisons.”

Money, Money, Money

Wake Forest, with its top-ranking education, research opportunities and parties, comes at a hefty price tag. For the 2019 – 2020 school year, total cost of attendance is roughly $74,424 dollars.

Despite being on the higher end of the cost of attendance range, Wake Forest has a price tag that is consistent with many of its equally small, equally selective liberal arts peer institutions. However, the university has a smaller endowment per student than many of its peer institutions, as Wake Forest became a national school long after its peer institutions did.

According to Bill Wells, the director of Student Financial Aid, about 47 percent of students pay full tuition. Given that they can afford to pay full price, those families’ incomes must be significant —and they are.

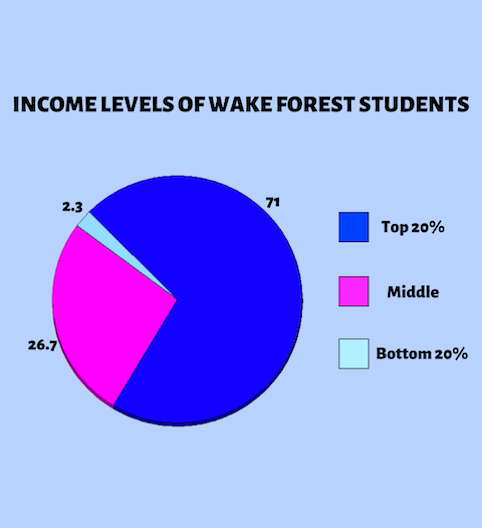

Seventy-one percent of Wake Forest students hail from the top 20 percent of incomes nationally, according to a report by the Equality of Opportunity Project. Within that, 22 percent come from the top 1 percent. Only 2.3 percent of students come from the bottom 20 percent of incomes.

Senior Austin Hill, who has experienced party culture from a distance as a student on financial aid, thinks that increasing the number of middle- and lower-income students on campus could lead to a shift in the party culture, which he described as inherently exclusive.

“We take way too many students who can pay out of pocket and I feel like because of that we don’t have a diverse student body,” Hill said.

This lack of diversity, especially in terms of socioeconomic status, creates a bubble in which the party culture exists, and it can be difficult to penetrate from the outside.

“All the sociological research shows that hook-up culture, heavy drinking, all those things bundled [in party culture] is an upper-middle class, white phenomenon,” said Nate French, director of the Magnolia Scholars program.

He added that Magnolia Scholars, who are first generation students and are typically from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, tend not to participate in party culture. As Wells said, it takes money and leisure to party — which the more affluent students have and less affluent students have not.

To increase the number of students from lower socioeconomic statuses, Wake Forest first has to — and has been working on — increasing the endowment for scholarships through donors, Wells said.

“It’s a heavy lift,” he said. “We will eventually do this, but [it’s] not going to change overnight.”

The Greek Connection

Some attribute Greek life as the cause of party culture; others say that it would still exist without it. But, it is undeniable that Greek life is connected to these intersecting issues of affluence and party culture.

According to Cornell University, while only 2 percent of the U.S. population is in fraternities, 80 percent of Fortune 500 executives, 76 percent of U.S. senators and congressmen, 85 percent of Supreme Court justices and all but two presidents since 1825 have been in fraternities. With these high positions come money and status that breed more money and status, and in turn, more wealthy Greek life participants.

“At most institutions, Greek systems begin to connect to a class elite because you are paying monthly fees, as well as tuition and other stuff like that,” said French. “And your work study can’t pay the fraternity or sorority bill, or at least it usually can’t.”

Wake Forest has a high percentage — over half — of students who participate in Greek life. With semesterly dues upwards of several hundred dollars, the additional money required for that can make it appear that Greek students are also the ones who can afford to party.

“It costs a lot of money to be in Greek life, so a lot of those kids are the ones primarily involved in the party culture,” said junior Maren Morris, who was in a sorority before disaffiliating due to her growing dissatisfaction with the upkeep of status and image associated with it.

And even though Greek life is not just centered around partying, they are often the ones throwing the parties and providing alcohol, Morris said.

“The kids that are able to go out and party all the time, I don’t know how much responsibility they have,” Morris said. “Which makes me think that perhaps their lifestyles back home have maybe given them a sense of entitlement.”

The dues and other costs associated with being in Greek life can be a barrier for students of a lower socioeconomic status, which in turn has it appear to be only for the wealthy students.

“It’s been a criticism of fraternity and sorority life for a very long time that it’s an elitist group and it’s a pay-to-play deal where you pay for your friends,” said Betsy Adams, director of Fraternity and Sorority Life.

While there is national data that supports that large Greek communities, such as the one at Wake Forest, correlates with higher rates of problematic drinking, it’s not the ultimate cause. Those who desire to party will seek it out and find it.

Referring to alcohol, Adams said, “If you don’t have the money to get it yourself but there were places where you could get it for free, you’d probably find where you could get it for free.”

And free alcohol doesn’t just translate into fraternity party, it’s any party. But first, one has to know how to get in.

The Know-How of Getting an Invitation

Senior Austin Hill noted that it was the higher-income students who always knew about the parties, even though everyone wanted to get in on them. He remembered that as a freshman, on the first day of classes, everyone was talking about where they had gone out the night before and where they were going that night.

“I was like, ‘How do you know about all this?’” Hill said. “And they answered that they’ve been doing programs here for a few years now and were here for the pre-orientation programs. I couldn’t do those things because they were expensive.”

As Hill’s story exemplifies, a student needs to know how to make the connections that will allow them entrance into this party culture.

“It’s problematic because it’s not open to everyone,” French said, referring to the party culture. “On the other hand, it can teach students how to navigate the world [of networking].”

Even if it can teach other students how to navigate the social world, the students from higher socioeconomic statuses already have the connections and already have the ability to access alcohol or an invitation to the party. While money is not the sole causative factor to party culture, it definitely plays some role.

“Money’s a prerequisite,” said Wells. “You’ve gotta have it in order to be able to do it.”