Senior Debbie Marke just wanted to go home.

After a bad experience at a party one night during her freshman year, Marke, who is black, decided to walk back to her residence hall, trying to fight the tears running down her face.

But as she passed by the library, following the raucous crowds of drunk, white students stumbling back to first-year housing, she was approached by two campus police officers.

She thought they were going to ask her why she was upset.

Instead, she says the two officers demanded to see identification to prove she was a student. As she stood crying in front of them, the officers detained her for what felt like minutes. They looked down at her ID, looked back up at her, then down again, then up again. The officers released her, but she said they did not stop any of the other students around her to conduct the same ID check.

“It’s a pretty degrading feeling,” she said. “It makes you feel like you don’t belong and that you’re an ‘other.’”

Marke is one of many black students who shared their stories as part of an OGB investigation into claims of racial bias in Wake Forest’s police department.

Reflecting a trend nationally, and especially among students at Ithaca College in upstate New York and Providence College, many black students at Wake Forest say that they have been profiled or singled out by University Police simply because of their skin color. These allegations mirror larger protests around the country in cities like Ferguson, Mo., Greensboro, N.C. and Chapel Hill, where mounting evidence shows an unusually high number of confrontations between local, mostly white, police forces and black citizens.

Wake Forest faces similar racial disparities between the number of black and white students arrested or stopped for identification on campus, according to an analysis of statistics hidden in plain sight on the WFUPD website in the Williams/Moss Report and the Yearly Arrest Data.

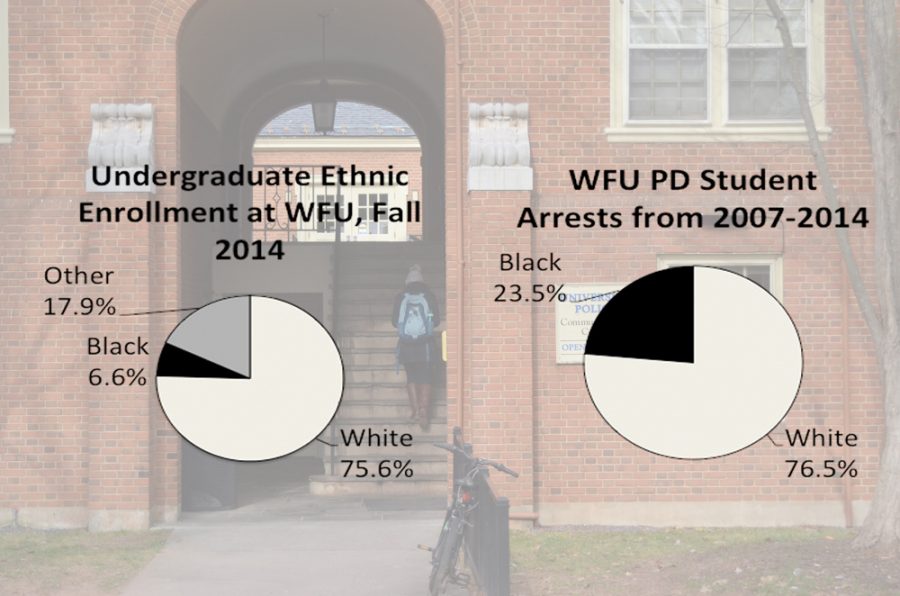

Black students attending Wake Forest made up 23.5 percent of arrests between 2007-2014, despite representing just 6.6 percent of the campus population. This means they were arrested nearly four times as often as white students.

“I can’t say I’m surprised,” says Akosua Tuffuor, a black senior from New Jersey. “People know racial profiling exists on campus. Our campus is not the bubble people think it is. So goes Wake Forest, so goes the nation.”

In response to the statistics available on her department’s website, Regina Lawson, the chief of Wake Forest’s Campus Police, said in an interview with the OGB that while the numbers are concerning, she believes they show no evidence of racial bias in the department.

“We’ve had it investigated,” she said. “At this point, we’ve taken all the measures we can to determine that when we take enforcement action, it is always fair and equitable and not motivated by race.”

Following multiple allegations of racial bias by students in the spring of 2014, Wake Forest hired Developmental Associates, a consulting firm, to investigate the claims.

“We wanted to have an objective third-party investigation,” Lawson said.

“We brought [Developmental Associates] in to look at the allegations and determine if they were substantiated or not.”

The released analysis, known as the Williams/Moss Report, concluded that “none of the allegations of racial bias rose to the level of actual racial bias,” and that “one cannot assume that racial bias is a factor in arrests by campus police officers.”

To provide evidence for these assertions, the report compares the percentages of black students and white students arrested at Wake Forest to the percentages at 34 other colleges in North Carolina.

However, it does not take the proportional racial makeup of each college into account when comparing the statistics.

“Without proportion, that comparison is meaningless,” says Sara Dahill-Brown, a professor of politics and international affairs.

“In addition to presenting fairly specious logic, much of the data included in the report has little bearing on the questions that it was supposed to address.”

While the report acknowledges that minorities are arrested in greater percentages than their proportional representation on campus, it states, “These numbers are clearly in accord with state and national trends … we see no bias as it pertains to the issue of race in arrest situations.”

Wake Forest may mirror national trends in its arrest record of black students, but that bar isn’t very high. According to a 2014 USA Today report, blacks are more likely than other races to be arrested in nearly every city for every type of crime, from loitering and marijuana possession to murder and assault. The investigation shows that in Winston-Salem alone, black residents were arrested at a rate three times higher than whites based on statistics from 2012.

The Williams/Moss Report’s comparison to current trends doesn’t sit well with some students.

“It’s an attempt to normalize this plague of racial profiling on this campus,” says William Ray III, the leader of the Black Student Alliance at Wake Forest. “It’s saying, ‘Yes, there’s a gap here, but it’s OK because everyone else is doing it too.’”

The report provides no further analysis to explain its assertion that no problems exist.When asked to clarify the conclusions made in the report, Chief Willie R. Williams, the head of the investigation, responded in a phone interview: “I don’t think there’s anything else to add or explain in the report. I don’t feel comfortable talking about it. Those are the results of our investigation.”

Lawson said that the analysis was “more of a courtesy compilation of the data that was available,” and that the lead investigators, Chief Williams and Chief Tom Ross, were neither statisticians nor researchers by trade.

The Williams/Moss report concludes with recommendations for WFUPD to improve relations with minority students on campus and to help eliminate the “perceived bias” of the students who filed the allegations. The WFU Police Accountability Task Force — a group of administrators, professors and alumni — has helped to implement those recommendations in the department.

“We’re keenly aware [of the issues] and aggressively working on procedural justice, fair and impartial policing techniques and alternatives to arrests,” Lawson said.

Many black students say the changes aren’t enough.

“They’re doing enough to put a Band-Aid on the situation and keep up their appearances,” says D’Andre’ Terrence Starnes, a black graduate student from Winston-Salem. “They should continue investigating to see if this problem really is pervasive.”

All of the students interviewed for this investigation said that numerous instances of racial bias go unreported on campus.“Many of the students who have had run-ins with campus police choose not to report them because they feel that nothing will come of it,” Ray said.

“As a student leader, I can’t feel comfortable telling people of color to come here when that is the atmosphere that I’m bringing them into. I feel like I’m bringing them into a burning house.”

Most just want the department to admit that racial bias, conscious or unconscious, might play a factor given the large disparity in arrests.

“Why can’t they just admit there’s a problem?” Marke said, reflecting on her experience with University Police. “How can we move forward with talks of diversity and inclusion on this campus when the police can’t even admit that racial bias is even a possibility?”

ZXa321 • Jan 24, 2016 at 6:45 pm

This conclusion is what concerns me the most:

“These numbers are clearly in accord with state and national trends … we see no bias as it pertains to the issue of race in arrest situations.”

We know that the nation has a problem with racial discrimination, so we at WFU who are supposed to follow a PRO HUMANITARIAN motto, are supposed to be OK with this statement? I don’t think so, we should strive to create a better environment for ALL STUDENTS. The police force who are supposed to be the “keepers of the peace” have to do better that this. This is shameful!