Unity in Yemen is not a logical solution

Many Yemenis are dissatisfied with the results of unification in 1990, which has failed to bring peace

The war in Yemen has dragged on for almost a decade.

February 24, 2022

Within a month, the war in Yemen will have reached its eighth year. These years of intense fighting have produced what many consider to be the world’s worst humanitarian crisis. The conflict has killed over 100,000 people. More than 20 million Yemenis are in need of humanitarian support. Twelve million are estimated to be in acute need, and roughly five million Yemenis will be at risk of famine this year.

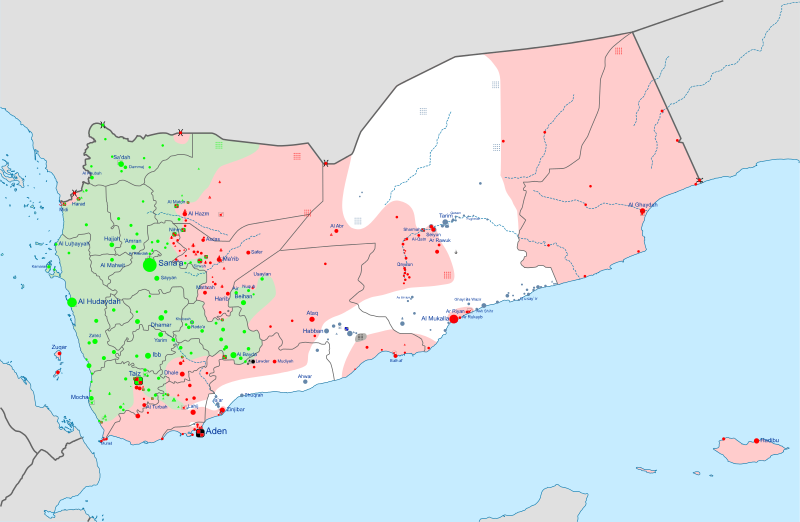

The world’s forgotten war began in 2014, but its roots can be traced back to the legacies of imperialism and the failed unification of the north and south regions. The conception of Yemen as a unified state — a myth promoted by successive imperial powers — is contrary to the country’s historical trajectory. Yemen’s social and political divisions remain a barrier to any meaningful peace efforts.

Historically, there has been a division between north and south Yemen. North Yemen was occupied by the Ottomans from 1872 to 1918, who brought the north into the empire-wide program of Tanzimat reform. These reforms — coupled with the encroaching presence of the Ottomans — marginalized the long-standing Zaydi-Shia imamate in the north, resulting in revolt. By 1918, Zaydi-Shia Muslims declared north Yemen the independent Mutawakkilite Kingdom.

The colonial period put the north and south on different trajectories, with the north being consumed by infighting between republicans and monarchists. The Mutawakkilite Kingdom survived failed coups d’états in 1948 and again in 1955. The imamate remained until 1962 when civil war broke out between republicans and monarchists.

Both Egypt and the Soviet Union supported the north’s revolutionary republicans, while Saudi Arabia, Israel, Jordan and the U.K. supported the monarchy. Republican forces eventually prevailed and the Yemen Arab Republic was officially recognized by 1970.

South Yemen was designated as a province of British India in 1937. By the start of the Cold War, the British could no longer maintain a stable presence in Yemen. Pressured by the National Liberation Front (NLF) and the Front for Liberation of Occupied South Yemen (FLOSY), the U.K. declared a state of emergency in 1963. The NLF assumed power by 1967 and the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (PDRY) — the Arabian Peninsula’s only outspoken communist nation — was born. The secular socialism of the PDRY was undoubtedly a product of its unique historical trajectory. It is no accident that the south became a secular, socialist society while the north became a tribal republic.

North and South Yemen were thus independent states by the late twentieth century. However, relations remained uneasy, culminating in the South Yemen Civil War in 1986, which took a significant toll on the south’s administrative apparatus. By 1989, the Soviet Union was poised for collapse, leaving South Yemen without its primary benefactor.

The socialist south reluctantly accepted a unification plan with the Yemen Arab Republic, which was finalized in 1990. Ali Abdullah Saleh, the former president of North Yemen, came to govern the country. As Saleh consolidated his power through tribal alliances, a Zaydi-Shia group called the Houthis gradually rose to prominence in the north. In 2004, Hussein Badreddin al-Houthi launched a nearly six-year rebellion against the nascent Yemeni government.

While Saleh suppressed the insurgency, his grip on power began to slip by 2011. The Arab Spring renewed calls for reform and equality across the Arab world. Protests erupted in Change Square but were violently suppressed by snipers. Although Saleh claimed plausible deniability, Yemenis had seen enough, and his vice president Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi assumed the presidency. A national conference sought to calm the waters but dramatically failed. Saleh allied himself with the Houthi movement, seizing the capital of Sana’a and advancing south toward Hodeidah. He was placed under house arrest in Sana’a but managed to flee.

A Saudi-led coalition intervened in 2015 to restore unitary sovereignty and maintain Hadi’s presidency. Ironically, Saleh again switched course and allied himself with the coalition. Infighting between the Houthis and forces loyal to Saleh led to Saleh’s death.

The present conflict in Yemen is typically viewed through a lens that does not reflect historical realities. Many — particularly in the American media — suggest that the Houthis and Iran are responsible for the continuing war and ensuing humanitarian crisis.

There is some truth to these allegations of proxy warfare, but the reality is much more complicated. Hidden beneath the jubilee of the Arab Spring were renewed calls for north-south secession. Many in Yemen were dissatisfied with the result of unification in 1990 and remain so today. By reviewing the historical and cultural trajectory of the north and south, the follies of unity become even more apparent. Although Saleh recognized these divisions, his government proved incapable of containing the north and south within the confines of a fragile nation-state.

Repeated attempts at federalism have failed, but many continue to believe that unitary sovereignty is the only solution to Yemen’s political dilemmas. Unless peacemakers recognize the ahistorical nature of this proposition, Yemenis will continue to face the world’s worst humanitarian crisis.