Inside the fight to put ASL in the undergraduate curriculum

American Sign Language (ASL) is not a language students may currently take to fulfill their foreign language requirement

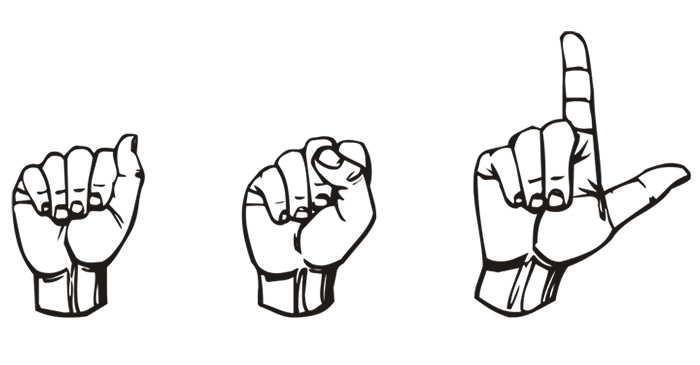

Photo courtesy of the ASL Club

According to the government of Rhode Island, there are about half a million ASL speakers in the United States.

October 10, 2022

The cornerstone of Wake Forest’s liberal arts education is its undergraduate curriculum, with five divisions and multiple miscellaneous requirements. One of these requirements is a foreign language, which requires that every student complete at least one 200-level foreign language class in their time at Wake Forest. The school offers a variety of language courses, from Arabic to Japanese to Spanish, but recently, some students have expressed concern that something is missing from the selection: American Sign Language.

American Sign Language, or ASL, according to the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, is “a complete, natural language… expressed by movements of the hand and face.” It is the predominant language of Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing communities in the United States and is decisively independent and distinct from English. With all the linguistic properties of a spoken language, such as pronunciation rules, word formation and syntax, it satisfies foreign language requirements at many high schools and universities across the country. Within the Wake Forest community, however, the only access students have to learn ASL is through a student-run club.

On April 6, students in LIN 310 held a Linguistic Discrimination, Diversity & Inclusion forum in which they presented “convincing arguments for ASL at WFU,” according to their professor, Dr. Tiffany Judy. As an associate professor and associate chair of the Department of Spanish and Italian, as well as the director of the linguistics program at Wake Forest, Judy offered some insight into the so-called “push for ASL.”

“One of the most common arguments made against recognizing ASL as an ‘official language’ at Wake Forest, meaning that it would satisfy the foreign language requirements, is that there is no written component,” Judy said.

Currently, the language requirement is fulfilled once the student reaches a “literature” course in their chosen area, but if ASL were introduced into the curriculum, this “university-wide criteria would have to be re-addressed.”

She revealed that there has been a concern in the past that the literature associated with ASL would be in English, making the classes “easier and more attractive to students,” and potentially threaten enrollment in smaller language departments. There is also the matter of funding; the inclusion of ASL classes would require funding to finance a search for professors and subsequent compensation. The “home department” of the hypothetical ASL division would also have to be decided, as LIN, or Linguistics is currently only a minor and relies on faculty from other departments.

“In order for our campus to be linguistically vibrant, it is important to maintain current language departments as well as determine where we may reasonably add new languages to our curricular offerings,” Judy said.

As far as progress made in the campaign for Wake Forest to offer ASL classes, Dr. Anne Hardcastle, the associate dean for academic planning, discussed a 2016 proposal that would have allowed students to fulfill ASL classes through an external program and apply them as transfer credits.

The proposed program included all languages not offered at Wake Forest – ASL was not singled out in this deliberation, as there are many languages not currently represented in the curriculum. Ultimately, however, the administration decided against this project, as it would “undermine the languages we do teach and the expertise of our faculty,” Hardcastle explains. The university would not have enough supervision of these programs and could not ensure the quality of the students’ education that is expected at an institution such as Wake Forest. Hardcastle also echoed Judy’s sentiments regarding the massive logistical project that an ASL class creation would entail.

The student-run ASL Club, headed by its president, junior Alex Latuda, meets weekly to share in their appreciation for the language. The club focuses on the instruction of ASL, with the help of Aimee Falk, the lead ASL teacher for Forsyth County Schools. Falk began the first meeting by teaching members the alphabet, basic signs, and fostering discussions amongst the group about the culture of ASL. According to Falk, concerns about the absence of a written component “discount the richness [of the language],” as there are many other elements not found in spoken languages.

“It speaks to the uniqueness [of ASL], not insufficiency,” says president Latuda.

For example, “mouth morphemes” — movements you make with your mouth while signing — are an integral feature of ASL. Facial expressions and body language are also important because they can actually change the meaning of a word or sentence. Sentence structure, “double letter” procedure, formal and informal conversation, regional dialects and many other procedures make ASL a complex mode of communication. There are rules — and exceptions to the rules — just like in any other language.

A large portion of the meeting concentrated on the rich culture associated with ASL and the Deaf community. The topic of “name signs,” for example, demonstrates the indivisible connection that ASL has to its community of users. The only way for a person to obtain a “name sign” is for a Deaf person to offer them one after becoming acquainted with their personality, and the designated sign is often a reflection of their character. Falk also noted that the ACTFL, The American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages, recognizes ASL as a language.

While the ASL club offers an alternate avenue of learning for students interested in the language, there has been little progress toward the inclusion of official ASL classes at Wake Forest. Despite intermittent deliberations and conversations on campus over the past few years, there has yet to be a substantial expressed interest in the subject. Hardcastle advised anyone eager to advocate or express interest in ASL classes to reach out to the two student representatives for the Committee of Academic Planning.

Danielle Omvig • Oct 21, 2022 at 6:37 pm

We just visited wake forest on a college tour this afternoon. We were so impressed, but lack of ASL is a deal breaker for us. Our child has been studying asl in high school and hopes to become a doctor as well. He has no interest in starting a new language to fulfill the language requirement. He has a passion for asl and it fits well with his future occupational plans unlike some of the more obscure languages that the university offers.

John Overby • Oct 18, 2022 at 11:25 am

Have always thought this about Wake needing a sign-language class/department. Great work, Tenley!