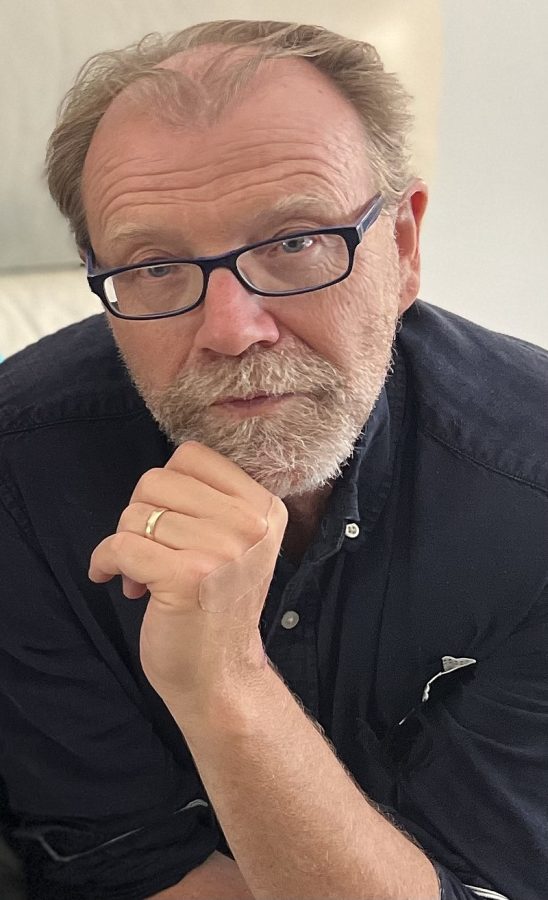

How George Saunders breaks your heart

The acclaimed author writes with incredible nuance

George Saunders writes devastatingly simple stories, but there is usually hidden meaning beneath.

November 30, 2022

George Saunders is one of the most successful and powerful fiction writers alive today. He has Thomas Pynchon saying good things about him, and he’s got Zadie Smith saying things like, “not since Twain has America produced a sairist this funny” — something that functions as a compliment in the superficial book review industry to which we’ve grown accustomed. One accurate review, though, from Joshua Ferris, describes Saunders as “very easy on the surface but incredibly difficult once you actually read him with any depth.”

Indeed, Saunders seems to be a master at writing for two distinct reading worlds. He can satisfy someone who’s looking for television-quality entertainment, and he can keep an academic up at night with the same story. It is my belief that his ability to reconcile these two worlds is what ultimately gives his stories their emotional punch.

In an interview with The New Yorker in 2020 about his most recent short story collection, Saunders said that his “main goal is to try to get the reader to finish the story.” I read this interview after completing his short story “Ghoul” — a tale of an abandoned, underground amusement park where no visitors ever show up, and the workers get kicked to death if they speak out of line — and I must admit I felt a little bit cheated, confused and even irritated. How could this story, which has so much going on, be made with such a simple, banal goal in mind?

A fundamentalist but not exactly fun way to go about explaining his work would keep in mind fiction writing as a profession and the art of adhering to consumer demands. It would imagine Saunders imagining his reader as a very busy woman who just got home from the grocery store and could easily turn on “The Real Housewives of Orange County” if she so pleased. But none of that is really romantic or conducive to understanding why Saunders is a great artist.

Instead, let’s take a look at one of his most celebrated short stories, “Sticks” (which is only two paragraphs long so, yes, I am expecting you to read it).

“Every year Thanksgiving night we flocked out behind Dad as he dragged the Santa suit to the road and draped it over a kind of crucifix he’d built out of metal pole in the yard. Super Bowl week the pole was dressed in a jersey and Rod’s helmet and Rod had to clear it with Dad if he wanted to take the helmet off. On the Fourth of July the pole was Uncle Sam, on Veteran’s Day a soldier, on Halloween a ghost. The pole was Dad’s only concession to glee. We were allowed a single Crayola from the box at a time. One Christmas Eve he shrieked at Kimmie for wasting an apple slice. He hovered over us as we poured ketchup saying: good enough good enough good enough. Birthday parties consisted of cupcakes, no ice cream. The first time I brought a date over she said: what’s with your dad and that pole? and I sat there blinking.

We left home, married, had children of our own, found the seeds of meanness blooming also within us. Dad began dressing the pole with more complexity and less discernible logic. He draped some kind of fur over it on Groundhog Day and lugged out a floodlight to ensure a shadow. When an earthquake struck Chile he lay the pole on its side and spray painted a rift in the earth. Mom died and he dressed the pole as Death and hung from the crossbar photos of Mom as a baby. We’d stop by and find odd talismans from his youth arranged around the base: army medals, theater tickets, old sweatshirts, tubes of Mom’s makeup. One autumn he painted the pole bright yellow. He covered it with cotton swabs that winter for warmth and provided offspring by hammering in six crossed sticks around the yard. He ran lengths of string between the pole and the sticks, and taped to the string letters of apology, admissions of error, pleas for understanding, all written in a frantic hand on index cards. He painted a sign saying LOVE and hung it from the pole and another that said FORGIVE? and then he died in the hall with the radio on and we sold the house to a young couple who yanked out the pole and the sticks and left them by the road on garbage day.”

Whether you are reading that story for the first or 15th time, I’m guessing you are feeling slightly jarred. Like when you’re out walking and someone in very tight athletic clothing runs past you before you even have time to register their presence. Saunders is that kind of writer. He’s quick; he’s in and out, and you’re still thinking about him even after he’s crossed the street.

How does he do this?

I think one pair of sentences from “Sticks”, in particular, encompasses what Saunders does with the short story: “When an earthquake struck Chile he lay the pole on its side and spray painted a rift in the earth. Mom died and he dressed the pole as Death and hung from the crossbar photos of Mom as a baby.” In isolation, it becomes clear that he’s pretty much using the same tool experimental Soviet filmmakers like Kuleshov and Eisenstein used in the twentieth century — dialectical montage. Essentially, he’s constructing meaning at maximum efficiency by letting two vastly different sentences play off of each other and enrich one another.

What’s unique about Saunders’ juxtaposition, though, is that it’s not only used to make meaning bounce around like a beam of light between mirrors, but it also allows the story to advance at a staggering pace. It’s more than taking an absurdly funny line and putting it next to something devastating to create a unique emotional effect — it’s simultaneously generating movement, both within the reader and in the text. All of a sudden, this quirky anecdote about a dad who is a compulsive decorator turns into a sobering piece on grief and coping with mortality. In that small couplet, Saunders completely flips the tone and direction of the story.

This concept of moving with speed and purpose is one that is consistent throughout Saunders’ work. “It’s a story, after all, not a webcam,” he writes in “A Swim in a Pond in the Rain”. It would be an understandable yet grave mistake to overlook the fact that Saunders’ dedication to keeping the reader entertained and engaged and flowing alongside the story is doing more than helping him sell books — it’s actually one of his crucial devices for delivering pathos.

Let me try to explain.

The world that Saunders writes in is an extremely cynical and ironic one. It’s a world where there is little room, if any, for anything cliché, sentimental, authoritative or vulnerable. Saunders steers clear of excessively elevated language in order to avoid being seen as pretentious, and he uses humor and absurdity to avoid being seen as preachy or sappy.

He uses concise sentences that are jam-packed with meaning, each one leaping from its predecessor so that, before you know it, you’re engrossed in this world that is foreign and perplexing. You become uncomfortable and confused — entirely unable to make the kind of criticism applicable to the everyday world we know and understand.

The beauty of Saunders’ style is that it is right at the moment in which you begin to understand the story world — the moment in which you are learning to play by its rules — that he drops the emotional hammer on you. It’s the moment when you least expect it. It’s after a laugh or a smirk or a scoff, but it always comes. Just as soon as you think you understand this world that is bizarre and unrelated to you, Saunders makes his characters painfully real, and he shows you that you’re not much different from them, after all.

Saunders has mastered this timing mechanism. He knows exactly how long to leave you suspended in a bewildered state, and he knows exactly when to break your heart, too. What makes Saunders worth studying is the fact that he is a writer with the kind of dazzling postmodernist toolbox that excites and challenges the reader who’s interested in what stories can do, but he hasn’t lost or forgotten about that same reader’s visceral desires. He knows that at the end of the day, the goal of a short story is to move someone, to make them feel something. And isn’t it much, much easier to make someone feel a story when they’re sitting there and really believing in it?