Tunbjörk’s photography remains relevant

The Swedish photographer may not be around, but the way he saw the world still carries weight

In a Lars Tunbjörk photograph, a man stands in a yellow room.

February 15, 2023

Lars Tunbjörk was born in Borås, Sweden, in 1956, and he was one of the most talented and powerful photographers in the world when he died in 2015. He captured the madness of the American campaign trail, the eerie loneliness of the office cubicle, the quiet oddity of the suburban neighborhood and the joie de vivre bursting through the cracks of it all. In a mini-documentary, “Lars Tunbjörk, Beyond Backstage,” you can see how unimposing his craft was — how he could blend into a scene and capture life as it really happened.

Surprisingly, the result was often something that appeared more like fiction than the reality. In this lies the genius of Tunbjörk’s work:the idea that the standard mode of life is either comedy or tragedy — it’s rarely something to digest at face value.

Photography is tied to a certain time and place perhaps more strictly than any other art form. A novel, for example, can be written over the span of a lifetime, but the flash of a camera captures a fraction of a second. It’s fair to wonder, then, why it would be fruitful to revisit a photographer who has been gone for nearly a decade. The truth is, I think Tunbjörk’s photographs are only getting more accurate and relevant. He belongs to a rare, distinguished class of artists, as he truly impacted people with his work, even though he was way ahead of his time. In short, he led his followers into a brave, new world.

Despite knowing little about photography, I have always had a preternatural understanding of Tjunbörk’s photos from the moment I first saw them. I believe most people feel the same. Like a Virginia Woolf novel or a David Lynch film, you can feel something in your nerve endings that’s completely unique and new when you see a great Tjunbörk photo. Great artists seem to have this ability, to be able to package a universal emotion in a form or style that is so radically personal that the viewer has no choice but to view life anew. You don’t need a degree or years of analytical experience to see what Tunbjörk saw — you just have to look.

Aggressive flash and boisterous colors characterize most of his images, but it’s much more than that. His style is defined just as much by how it makes you feel as by how it actually looks.

If you scroll or flip through a collection of Tunbjörk’s images, you start to get this feeling that you’re observing humans — and the home they inhabit — for the very first time. Everything is defamiliarized and viewed in a different light. It’s like a curtain has been pulled away and you’re seeing the world how you should have seen it all along.

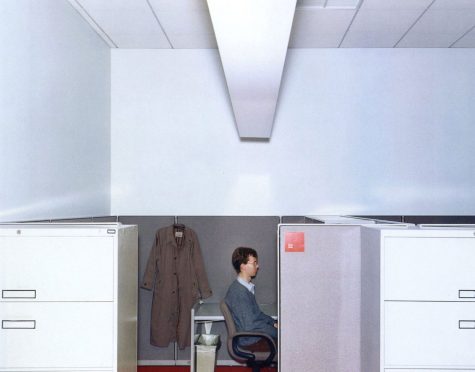

My favorite collection by Tunbjörk is his “Office” series. He completed it in the early 2000s after years of traveling across the world to photograph corporate office spaces in cities like New York and Tokyo. Oftentimes, the subjects of these photos are engulfed by the landscape surrounding them. Except, instead of being swallowed up by a sublime waterfall or a towering mountain, the subjects are surrounded by wires, computers, cubicle walls, paperwork and fluorescent lights. It’s a nightmare, and it’s funny, but it’s sad, too. Humanity has created the technology that subverts itself, and in one way or another, we chose this isolation and inferiority. Or at least some of us did.

The bleak and dreary nine-to-five workday is a common trope in the media today, but I’m impressed at how Tunbjörk found something unique to say about it back in the 2000s. He understood that the tragedy of the cubicle is not the long hours or the unfulfilling work but the alienation one feels when they’re cooped up for at least five days a week. Not only is it spooky, but it’s maddening, too. The disorientation of staring at a computer screen all day has the power to destabilize someone’s perception of reality — making them question their life altogether.

With the presidential primaries coming up, it seems especially appropriate to discuss Tunbjörk’s work covering the 2012 Republican primaries. On his assignment, he captured moments like Rick Santorum praying before a massive plate of nachos, a man covering his son’s ears at a Mitt Romney event in Des Moines, Iowa, and a town hall meeting with Newt Gingrich that was mostly attended by Caterpillar Inc. excavators. Tunbjörk described American politics as a circus, and who, in 2023, could disagree?

What I love about this series, though, is the disconnect between the politicians — or the image that they actively project — and the supporters who diligently follow them. The supporters, gathered around their heroes, often look so serious and concerned while the politicians seem relaxed to a saccharine degree. Here, Tunbjörk is highlighting the fact that politics in America is often nothing more than an amusing game for those already in power, one in which we, the people, get to play the part of the loser — and it’s fun.

Tunbjörk didn’t have the opportunity to photograph the 2016 election cycle, the COVID-19 pandemic or the global climate crisis as it has unfolded recently, but he left us with all of the tools to interpret it. When confronting the modern world, it is best to remember that things are never as dull or serious as they appear. There are ripples of hilarity, tragedy, absurdity and vitality wrapped up in everything you see, as long as you actively remind yourself that you are living — you’re living a life.