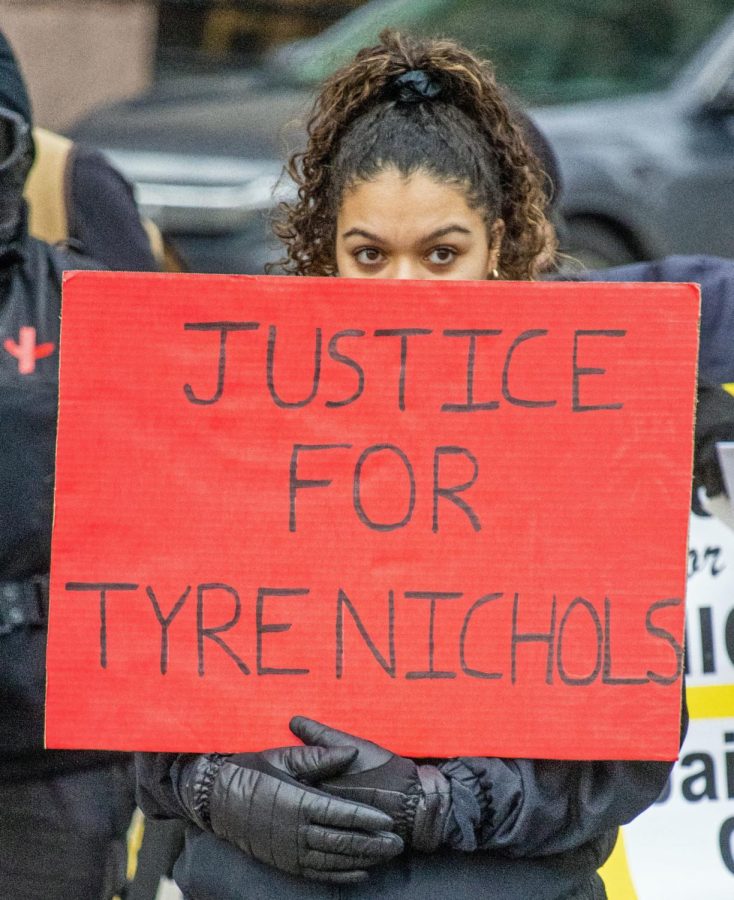

Tyre Nichols case exemplifies anti-Black violence

As one of nine Black men to lose his life to police brutality in 2023, Nichols’ case reflects institutional issues

February 16, 2023

On Jan. 7, Memphis Police Department officers battered 29-year-old Tyre Nichols after he ran from a traffic stop. Nichols was subsequently hospitalized in critical condition and died three days later.

As of Feb. 7, 13 officers have been disciplined, relieved of duty or dismissed in response to the Nichols case, and the Street Crimes Operation to Restore Peace in Our Neighborhoods (S.C.O.R.P.I.O.N.) unit responsible for his death has disbanded.

The release of video footage documenting the Nichols incident on Jan. 27 was met with numerous responses from police officers, activists and politicians alike. Patrick Yoes, the national president of the Fraternal Order of Police (FOP) said, “The event as described to us does not constitute legitimate police work or a traffic stop gone wrong. This is a criminal assault under the pretext of law.”

In response to Yoes, I pose the question “what is ‘legitimate police work’?” We live in a society governed by the prison-industrial complex, a term coined by activist Angela Davis to describe the system of labor by which incarcerated people are paid salaries as low as $0.04 an hour to support corporate businesses in a form of neo-slavery. In a capitalistic system that perpetuates state-sanctioned violence and profits from the brutalization and exploitation of Black bodies through the prison-industrial complex, is any police work legitimate?

Rather than asking what can be done to reform our policing system, the question we should really be asking is what can be done to abolish this institution entirely? Because our policing system is so deeply rooted in white supremacy and settler colonialism, reform is impossible, and these calls for reform — which so often come from white politicians and businesspeople in positions of great privilege — ring hollow. Policing in the United States finds its origins in 19th-century slave patrol groups, which had less to do with keeping crime in check and more to do with preventing enslaved people from dissenting and escaping. The first militarized police unit, established in Pennsylvania in 1905, was directly influenced by imperial warfare and focused its policing efforts exclusively on districts populated by “foreigners,” operating under the motto, “One American can lick a hundred foreigners.”

Despite popular opinion, policing has hardly departed from these origins. The impossibility of reform is exemplified by the popular Black Lives Matter movement and response to the deaths of Ahmaud Arbery and George Floyd. The individuals responsible for Arbery and Floyd’s deaths were convicted, and states like Colorado and Massachusetts passed laws intended to increase accountability and transparency in police departments as well as hire more qualified applicants. Yet, this cycle of violence has evidently not ended. As Audre Lorde famously wrote, “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.”

While Nichols’ case has received the most attention, he is not the only Black person to lose their life to police violence this year. On Jan. 2, 45-year-old Takar Smith was shot and killed by two Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) officers in response to a call for help from his estranged wife. The next day, 31-year-old Keenan Anderson died after being tased six times in 42 seconds on suspicion of a hit-and-run by several LAPD officers. On Jan. 4, a Houston police officer responding to a non-urgent call struck and killed 24-year-old Caleb Swafford. On Jan. 9, a unit sent by the Guymon Police Department in response to a call about a disgruntled employee at the Seaboard Foods pork processing plant in Oklahoma shot and killed 26-year-old Chiewelthap Mariar. On Jan. 19, 25-year-old Ronald Ray Mosley II was shot and killed by several Evansville, Ind., police officers. On Jan. 20, 39-year-old Leon Burroughs was shot dead by five officers in Jacksonville, Fla. On Jan. 26, 36-year-old Anthony Lowe, Jr., a double amputee, was shot and killed by officers in Huntington Park, Calif. On Feb. 2, 43-year-old Alonzo Bagley was shot in the chest by a Shreveport, La., police officer who was called in response to a domestic dispute.

While the details of these cases differ — some men were armed, while others were not, and some had engaged in criminal activity while others had not — none of these men deserved to die, and the scope of this violence and its impact on Black communities extend far beyond those who were killed. Racialized police violence and the brutalization of Black bodies is an epidemic, and until the policing institutions that commodify Black bodies and glorify violence through the media are abolished, there is no end in sight.

.

In the meantime, it is vital that we not only support anti-racist efforts such as mutual aid funds in support of people of color but recognize each and every Black person who has lost their life to police brutality as more than just a victim. Nichols, for example, was an amateur photographer with a 4-year-old son. In what lawyers believe were his final words, he called out for his mother, RowVaughn Wells, who described him as “a beautiful soul.” The two had an incredibly close relationship — so close that he ate dinner at her house every evening around 7 p.m. and had her name tattooed on his arm.

Takar Smith was a father of six who loved music and going to the beach.

“Anybody that knows Takar, they love him,” Smith’s brother Raischard Smith said.

Like Smith and Nichols, Keenan Anderson was also a father, as well as a 10th-grade English teacher and cousin of Patrice Cullors, a co-founder of the Black Lives Matter movement. On the website of Digital Pioneers Academy, where Anderson taught, he is described as “a deeply committed educator … beloved by all.”

Caleb Swafford was “the life of the party” and “made everybody laugh just being himself,” according to brother Cameron Swafford.

Each and every Black person who has lost their life to police brutality was a human being with hobbies and interests and friends and family who loved them. Yet the legacy of slavery persists. Black people are often depersonalized, dehumanized and not treated with the same human dignity afforded to those of us with racial privilege. Rather than trying to divert responsibility onto these people who didn’t deserve to die, we must recognize the fundamental problem — that society did not view them as human in the first place.

Whit Jr. • Feb 17, 2023 at 1:40 am

I’m sure Sophie is a wonderful person but the ideology that reeks from this column is so recriminatory I see little basis for consensus-building—indeed, I get the impression that my first duty as a white man is to beg forgiveness for my historical racism and then to take a knee, preferably wearing lipstick. May I dare to help without the masochism? We could make this a crude contest of who’s being most killed by whom, but that will never get us anywhere—except perhaps to secession. Our interest in solving this problem transcends racial or class categories. For example, just a few years ago a very white UNC student and fraternity president suffering a mental health crisis on his way home to Texas was pulled over by police and gunned down holding a cell phone. Perhaps had a psychology major like Sophie been first in their protocol her reassuring words could have defused the crisis and saved this man’s life as might hundreds of other Sophies saved hundreds of black lives in crisis in cities across the country. Sophie as first on the scene—the country is large enough to experiment with ideas like this and to find what works.