Why Wake Forest students need an algorithm to find love

Explaining what makes Marriage Pact so successful

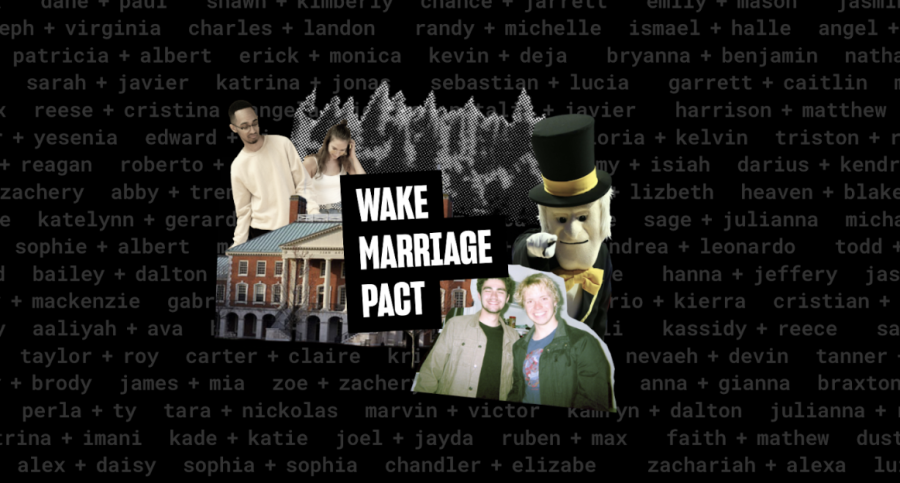

Over 2,000 Wake Forest students complete the Marriage Pact survey.

March 14, 2023

Just over 327,600 participants, 78 schools, 50 questions and an economic algorithm designed to help match you with “the one”: This is Marriage Pact.

The week of Valentine’s Day, with the subject of love still dense in the cool February air, news of a Wake Forest “Marriage Pact” swept through campus. Social platforms like Fizz and Instagram sprouted discussions, group chats grew tired with notifications and the question “Did you do Marriage Pact?” became commonplace in student conversations.

The data-driven possibility of a potential life partner was warm-welcomed on Wake Forest’s campus. After all, who knew? You might only be 50 questions and a short skip across the quad from meeting your soulmate.

Then, at 4 p.m. on Monday, Feb. 20, students across Wake Forest’s campus surrendered their 50-question surveys to the matchmaking algorithm of Marriage Pact. Founded in 2017 by two students at Stanford University, Marriage Pact combines psychology, market design and computer science to provide college students with the “most compatible backup plan on your campus, down to the percent.”

Come 10:30 p.m. later that same Monday night, amidst the inflated anticipation of hopeful romantics who had completed the questionnaire, the marital matches popped into student inboxes. The subject line read simply: “Match Announcement…”

Once again, the Marriage Pact news cycle was revived.

In the moments post-pact announcement, notifications fought for attention on my phone screen. Fizz. Instagram. Every group chat I’ve ever been remotely involved in throughout my time on campus. That night, the previous hot topic question yielded popularity to its successor: “Who’d you match with?”

In total, the Wake Forest Marriage Pact campaign received 2,068 submissions. On a campus of 8,963 students (5,447 undergraduate and 3,516 graduate, according to Wake Forest’s website), nearly a quarter of all students participated.

But how is it that something as simple as a dating questionnaire was able to strike such popularity across our campus and beyond? In an academic setting like that of “Work Forest,” where fatigue and burnout are mere side effects of a promising GPA, why are college students so eager to take another test?

Of course, we can’t discount the most obvious answer — it’s fun.

The questionnaire is low risk and high reward. At worst, you get a good laugh with your friends. But at best, you might meet your match made in heaven (or in this case, Palo Alto, Calif.).

But the anticipation that swept through Wake Forest speaks to something much larger looming on campuses across the country. Our school’s amiable acceptance of a marital “backup plan” can be attributed in part to two larger cultural trends currently facing our generation.

The first trend confronts our digital existence.

Dating apps, social media platforms and the general prevalence of smartphones have distorted dating culture as we once knew it. Where potential partners were once determined solely by geography, convenience and happenstance, we now have millions of potential partners available at our fingertips.

With a profile on Tinder, Hinge, Bumble or any other dating app, our generation is now plagued with the paradox of choice. This paradox, a psychological theory published by Sheena Iyengar and Mark Lepper in 2000, suggests that too many options can prompt decision-making paralysis. In the world of online dating, this translates to a cultural phenomenon in which participants in the dating pool either feel overwhelmed by the sheer quantity of potential options or unreasonably raise their standards to account for an illusion that a better match might exist in the next swipe.

From its creation, Marriage Pact was founded on principles of behavioral economics. By cleverly eliminating the paradox of choice, Marriage Pact was able to successfully capitalize on an experience that exempts choice altogether. For many students, this experience was alluring.

On top of that, Marriage Pact was a refreshing change from modern dating culture in that it circumvented society’s high standards placed on physical appearances. Unlike Hinge, Bumble or Tinder, Marriage Pact prioritizes moral values above all else, and participants lack the option to linger on looks.

So even on a small campus like Wake Forest, where the paradox of choice might be limited compared to larger schools, the Marriage Pact offered students a chance to meet their match without initial anxieties about appearance.

The second trend is a lasting byproduct of the pandemic — loneliness.

A recent survey conducted by Boston University reports feelings of depression, anxiety and loneliness in college students are at an all-time high. The survey specifies that “two-thirds of college students are struggling with loneliness and feeling isolated.”

The COVID-19 pandemic, at its peak, predisposed us to intense feelings of isolation. In the aftermath, the pandemic atrophied our social skills. Unsurprisingly, it also affected modern dating culture. Dating app activity surged during the pandemic. In a positive feedback loop, the pandemic exacerbated loneliness, which promoted singles to turn to dating apps, paralyzing them in their abundance of choice and leaving them feeling lonely and overwhelmed.

Again, amidst this feedback loop, Marriage Pact creatively intervenes. A dating questionnaire is all that’s separating you from a promising marital backup plan. With it, you can evade the existential question of dying alone.

So on college campuses, a once ideal setting for meeting your potential partner, the scene has shifted. Loneliness and technology have compounded on one another to exacerbate existing changes in dating culture.

And the solution? How are college students supposed to find a match amidst these daunting trends in modern dating?

Well, the answer might just lie in 50 questions and an economic algorithm.

Correction March 14, 2023: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated the position of Ashlyn Segler. She is a staff columnist.