On a regular February morning in 2014, Elizabeth Kuehn didn’t wake up to her alarm.

Instead, she woke up to something alarming — a male student raping her.

Afterwards, Kuehn, then a sophomore, knew what happened but couldn’t process it. She didn’t cry for two weeks. She blamed herself for months. She constantly worried about taking action against her rapist, wondering if she could prevent him from doing it again.

In the four years that have passed, Kuehn fought to take back control and to heal.

Despite her accomplishments, the #MeToo movement caused Kuehn so much discomfort that she originally did not want to speak out.

When a man tried to grab her underwear through her dress in a bar, Kuehn decided her time had come. She recently published an online article, “Time for Me to Say #MeToo,” about the mental process behind her recovery.

“It’s a lot easier to be vocal when you’re angry than when you’re sad,” Kuehn said.

The #MeToo movement gained traction in October when, in the wake of scandals such as the Harvey Weinstein accusations, actress Alyssa Milano encouraged her Twitter followers to post their experiences of sexual misconduct online or to simply respond with #MeToo, assuring other survivors that they are not alone.

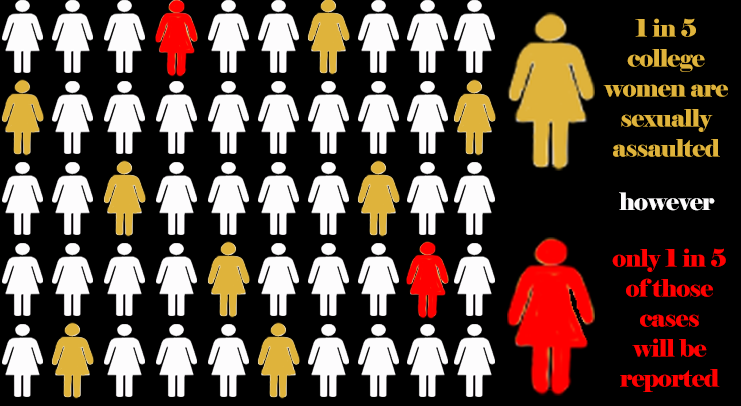

While #MeToo has empowered many people to come forward with their stories, the high frequency of sexual assault on college campuses, including Wake Forest, remains unseen. The Bureau of Justice Statistics reported that 80 percent of sexual assaults committed against college women go unreported.

“We have no reason to believe that the Wake Forest campus is any different,” said Tanya Jachimiak, the Title IX coordinator. “We do know that the number of reports that we receive do not capture all of the survivors out there.”

There are many factors, both social and personal, that affect a student’s decision to report sexual violence. According to Steph Trilling, assistant director of the Safe Office, these can range from fear of not being believed to worries about consequences.

“Many students say that after an experience of sexual misconduct they just want things to go back to normal,” Trilling said. “Participating in a reporting process can remind them of their experience, which may contribute to further emotional distress.”

In May, Kuehn wanted to report with the school, but as her rapist had graduated, she would have had to press official legal charges. After talking with a criminal defense lawyer who told her that she had a strong case, Kuehn weighed her options. In the end, she made the right decision for herself: to not press charges.

“I thought it would hinder my healing process to have to go through that,” Kuehn said.

Exactly how many collegiate cases exist is hard to discern due to the lack of reporting. A poll by The Washington Post reported that 1 in 5 collegiate women are sexually violated.

According to the Wake Forest Annual Crime and Fire Report, there were 12 reported cases of fondling on campus from 2014 to 2016 and 10 reported cases of rape on campus in the same period.

Juniors Katy Marget and Emily Walton believe there is a high prevalence of sexual misconduct on campus. Together, they run an online blog, titled ‘End the Silence, Wake Forest,’ which publishes anonymous submissions from Wake Forest students in an effort to raise awareness about sexual violence.

On average, they receive three to four submissions per semester of direct stories about experiences of sexual misconduct in addition to the many that express support of survivors.

Marget believes that the anonymity gives more power to the stories than it might take away in how it exemplifies the prevalence of sexual misconduct.

“When you’re reading [the blog], it’s someone you could have class with, it’s someone you could walk by every day,” Marget said.

After publishing her article, Kuehn received responses from 14 current and former Wake Forest students — many of whom she didn’t know — who shared with her their similar experiences. In the era of #MeToo, Kuehn hopes that the stigma of sexual misconduct will dissipate.

“It shouldn’t be that scary for me to tell people that I was raped because I didn’t do anything wrong,” Kuehn said. “What am I so afraid of?”

bckn • Mar 30, 2018 at 12:45 pm

Often in campus assault, you are talking about people are on the own for the first time in their lives, who have never had contact with law enforcement. It can be very intimidating to go to the police- those guilt trips you put yourself through will be negatively validated and magnified- although it is irrelevent they will ask: what you were wearing, did you flirt, how forcefully did you say no, where are your injuries if you resisted, etc. etc. Victims hope the University will treat this in a fair way that also is more evolved and respectful in terms of victim-blaming. Universities do have a role, and if they do it right it can result in a fair outcome that could even allow for certain offenders to have access to restorative justice.

ZXa321 • Mar 18, 2018 at 6:05 pm

So what is the problem with calling the Winston Salem police to press charges against a rapist? The minute it happens you empower yourself to take charge of the situation instead of leaving in the hands of those who want to protect the university’s policies.