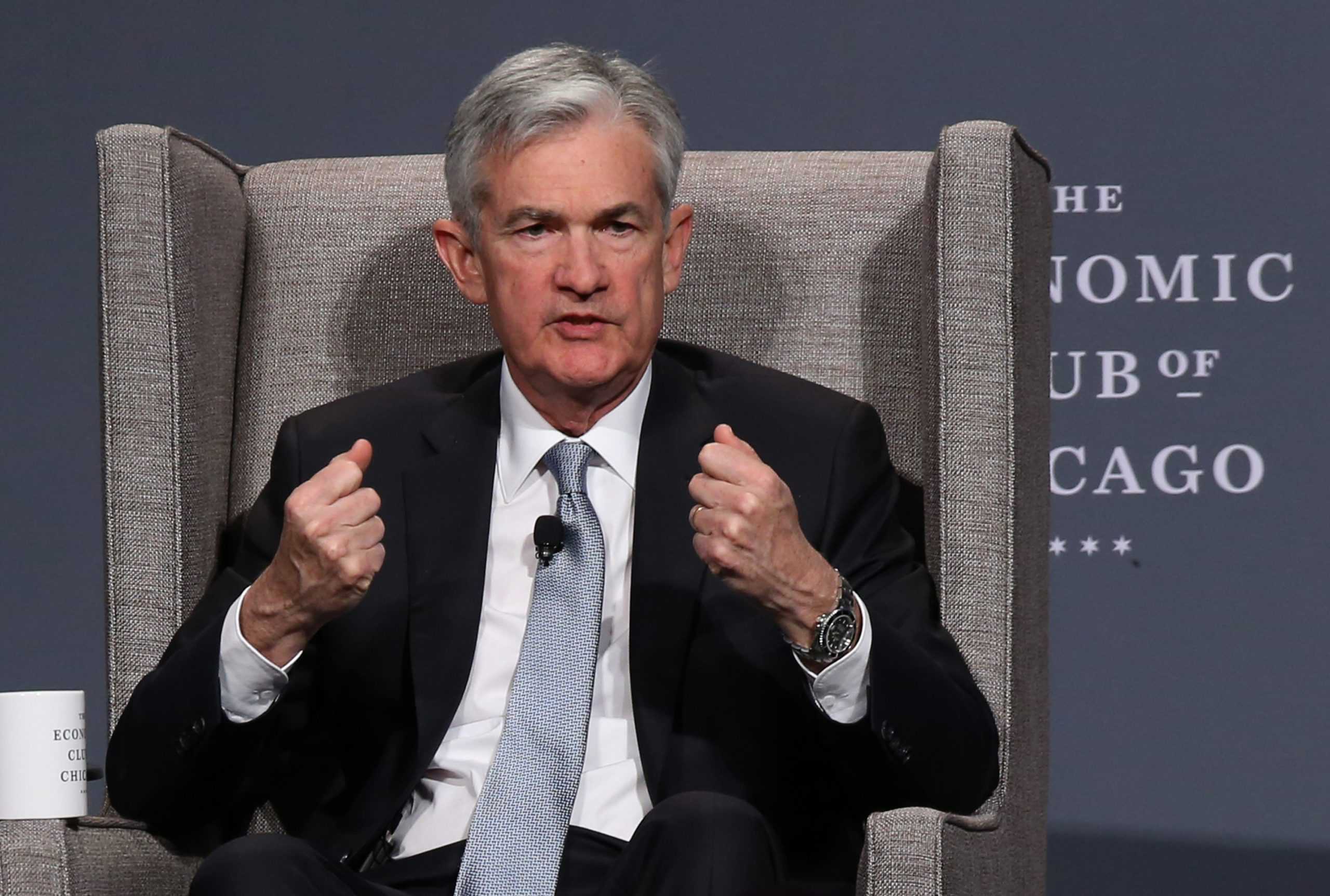

Last week, President Donald Trump blamed Federal Reserve chairman Jerome (Jay) Powell for a string of negative economic developments, including the stock market’s recent haircut and General Motors’ plan to close U.S. factories.

“I’m doing deals and I’m not being accommodated by the Fed,” he said in an interview with the Washington Post. “They’re making a mistake because … my gut tells me more sometimes than anyone else’s brain can ever tell me … I’m not even a little bit happy with my selection of Jay. Not even a little bit.”

The president’s comments were merely the latest in a long pattern of criticism directed towards our nation’s central bank.

Earlier in October, Trump had criticized the Fed’s recent policies, which have tightened lately but are still considered accommodative. He remarked, “The Fed is going wild. I mean, I don’t know what their problem is that they are raising interest rates and it’s ridiculous … The Fed is going ‘loco’ and there’s no reason for them to do it. I’m not happy about it.”

In contrast to many of Trump’s other unorthodox habits, his antipathy for the Fed’s interest rate increases is not particularly unprecedented.

It is obvious why politicians have an incentive to push for lower interest rates.

In the short run, an easier monetary policy boosts employment and squeezes out a little bit of additional growth, which is particularly desirable in an election year.

At the same time, there’s a reason why the Fed is built to be independent from political influence.

Easy-money policies, especially when conducted in times of expansion, lead to inflation. This problem is compounded if market participants come to presume that the Federal Reserve will lean whichever direction the political winds are blowing — they adjust their expectations in anticipation of easing, and wages and prices consequently spiral up.

Clearly, putting monetary policy in political hands, or even creating the public perception that it is, can be disastrous.

Politicians are focused on near-term economic success and aren’t as concerned about ephemeral sugar highs that are liable to crash after they leave office.

In contrast, Fed economists and governors rightly have no political stake; they aren’t afraid to “take away the punch bowl just as the party gets going” when the long-term good of the economy calls for it.

Who would we rather make these technically grueling and politically crucial decisions? It definitely shouldn’t be the politicians.

Luckily, though, there is good news from the most technocratic branch of the bureaucracy.

At the moment, it appears that the course of monetary policy has remained even-keeled, proceeding smoothly along a path of gradual rate increases that the central bank commenced in 2015.

The consensus among economists is that the Fed’s actions are cautious, deliberate and entirely backed up by objective analysis.

The data indicate that the economy seems to be strong enough to tolerate tighter credit — the unemployment rate of 3.7 percent is the lowest since the 1960s, inflation is ticking up and growth in the second quarter of 2018 exceeded four percent. The Fed deserves much credit for shepherding the economy into its longest recovery on record.

Moreover, all things considered, monetary policy since the Great Recession has been remarkably lax.

Although the financial crisis occurred nearly ten years ago, the target nominal federal funds rate, which is the Fed’s primary policy instrument, remained at approximately zero until only recently.

The Fed currently targets a funds rate of between 2.25 and 2.5 percent, but even now, with the consumer price index up 2.3 percent over the past year, that amounts to an interest rate of zero in real terms.

While economists may disagree about the exact pace of rate hikes, raising them gradually, generally by just 25 basis points at a time, is hardly “loco.”

Additionally, it’s prudent policy — raising rates during an economic expansion, or “fixing the roof while the sun still shines,” will allow the Fed more leverage to cut rates in a future downturn.

There’s no question that the Fed is doing the right thing, and as long as it remains committed to unimpeachable independence, we can be sure that policy decisions will continue to be informed by smart data analysis conducted by the best economists.

This may be the only column ever in which I will encourage my readership not to worry too much about the president’s behavior.

Lyndon B. Johnson heavily criticized then-Fed chair William McChesney Martin; Harry Truman urged the Fed to maintain easy-money policies; I’m sure that Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan weren’t thrilled when then-chair Paul Volcker raised rates to crack down on inflation. Similar things have happened before, and the Fed carried on.

In a time when many other institutions appear threatened, we need not worry about the Fed. It will continue to pursue its mandate with coldly apolitical expertise.

TD • Dec 8, 2018 at 3:19 pm

According to the Saint Louis the Fed Ten year Treasury Bills from the early 1960s (as far back as they post) until the Bush/Cheney Great Recession were never this low.