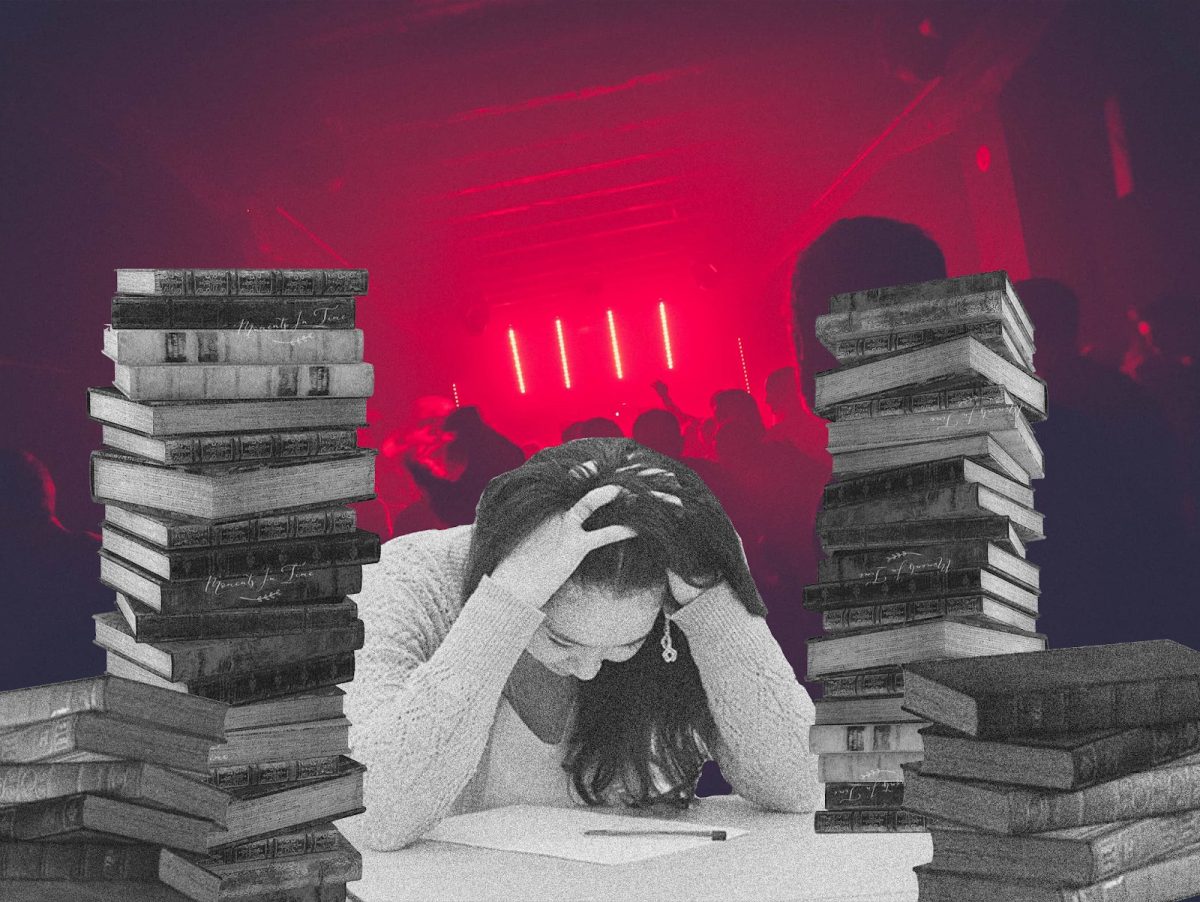

I have commented before on our culture’s instantaneity and its weakening of artistic memory. On-demand art, via Spotify stream, Amazon order or online publication, allows us to consume more (while also limiting intake to our perceived preferences); yet it also tends to hamper complex digestion of thing things we consume. The lack of cultural investment truncates experience and leads to a weightless rendering. Going to the bookstore, waiting in line to see the movie, buying a record and having to scrutinize it because it was the only option — all these processes subjectivize art into an attenuated adventure and are bound in our mind by a larger memory. Various art emporia, says Sven Birkerts, were not only commercial enterprises, “[they] also symbolized the presence, the value, of their product in the community.” The semi-scrupulous click flashes across the mind as a starburst, slighting the intellect and dictating the experience to come. If art fails to stimulate us in a period commensurate with its procurement, we abandon it. Speed influences how we are disposed to think about art, and now, with all of it summoned on a whim, our minds have become equally fickle.

Marshal McLuhan, 20th-century media theorist, was one of the first to link technology’s schemata to our own: “It is not only our material environment that is transformed by our machinery. We take our technology into the deepest recesses of our souls. Our view of reality, our structures of meaning, our sense of identity — all are touched and transformed by the technologies which we have allowed to mediate between ourselves and the world. We create machines in our own image and they, in turn, recreate us in theirs.”

McLuhan’s statement represents less of a dystopian prophecy than a logical assessment. Why should humans think they can create without being influenced by their creation? Technology is just another a manifestation of our ceaseless desire towards omniscience. Ever since we created God, he has engendered a generous amount of human aspiration, and technology has become our best lurch toward the heavens; yet it ironically remains a machinery so distant from our capabilities that it becomes as laughable as its qualities are unrealizable. As Frederick Douglass said, “man is worked upon by what he works on,” and technology has manipulated us, quite appropriately, into skimmers. The Internet realizes omniscience because of its inhumanity; its effect on the limited human mind reduces thought to recall, equating omniscience with an ocean of meaningless fact.

Since systems and circuits dominate our increasingly digital experience of the world, they sap from us the vital texture of memory. Online, individual humanity is subsumed by the collective, forming a dull and reliant self, dependent on network instead of nuance. The hive-mind escapism banalizes opinion and makes the individual an artifact, while art becomes curated by an algorithm, quicker than you can click, but quick enough to trick the imagination into thinking it’s working. We now lack confidence in knowledge because there exists a “specter of mass existence,” (Birkerts) that looms over our timid strand of self-actualization. How do we invest in art if we can’t formulate a stable opinion? The analog era existed in the physical world, but now it is either hidden behind the screen or mediated through it.

It is often espoused that objective knowledge and ideological templates alone cannot sustain human existence. There must be room for subjectivity and change — as products of nature we require such allowances; yet as animals capable of reason, we often try to suppress them. The screen has diluted subjective life into a life presented instead of generated. We tune our inner life to the Internet’s proffered waves of experience. Everything, including our personal life, is framed by technology. No longer our instrument, technology has become our god, or rather, as Nicolas Carr says, “It is so much our servant that it would seem churlish to notice it is also our master.” It is indeed our master, trapping the mind in its unrealizable framework, replacing memory with sights, vision with image. Carr also says, “Outsource memory, and culture withers.”