Leaving for spring break, I felt like I possessed an aura of invincibility. While I was aware of the spread of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19), I remained confident in its inability to affect me or my daily life. One professor suggested we bring our textbooks with us, but I had little doubt that we would return to campus a short week later.

Yet this bubble popped when one of the family members I was visiting came down with flu-like symptoms. As a public school teacher, she did what we are all told to do: contact her doctor and ask for a test. However, as she had neither had contact with a known case nor traveled outside of the country, she did not receive a test and was told to self-quarantine for two weeks.

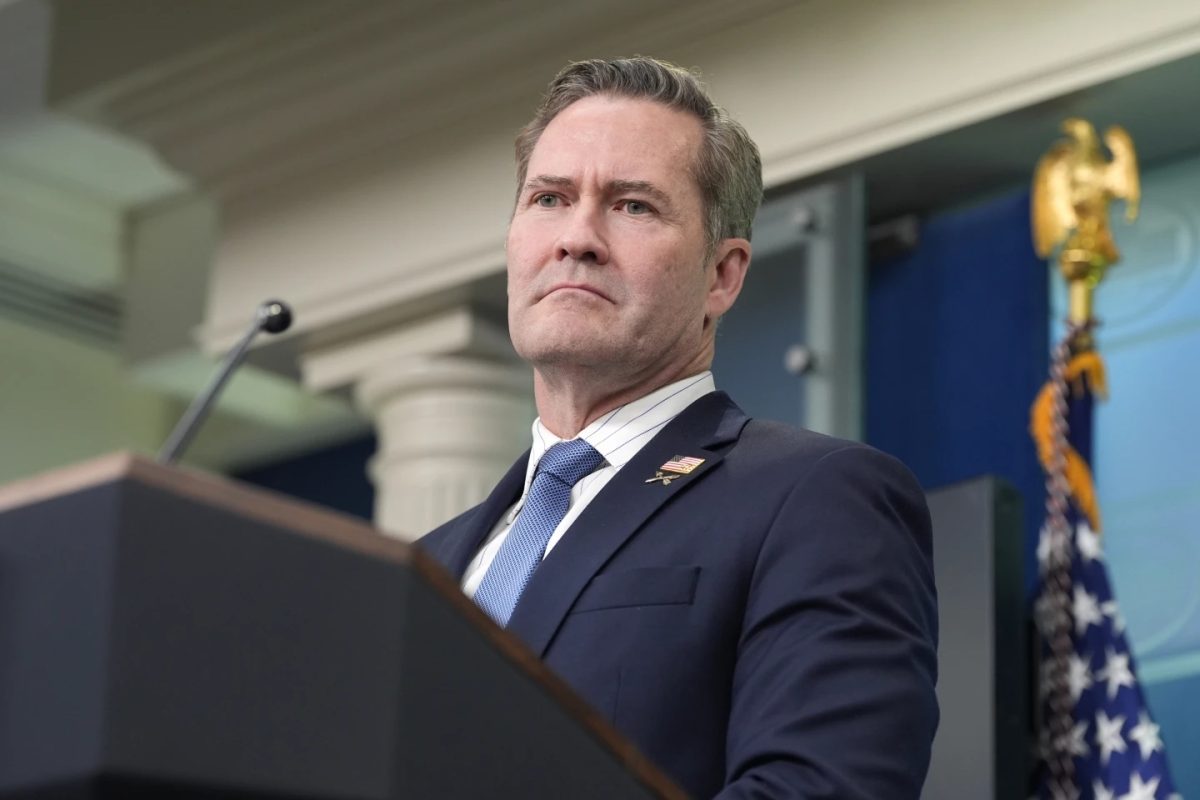

When the university cancelled classes, my parents insisted I come home instead of continuing my break. The first full day I was back, I found myself in an emergency room awaiting the administering of a COVID-19 test. Although I was asymptomatic save for a slight sore throat and did not fit most of the standards set by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), I received a test with few questions asked.

The test consists of two swabs, one in the nose and the other down your throat. I waited three days for results and tested negative for COVID-19. Yet, in the days it took to process the test results and in the hours it took to administer the test in the hospital, the glaring inefficiencies of our response to COVID-19 and of our American healthcare system were easily perceptible.

I was lucky to be tested. In fact, at the moment I am writing this article, the United States has performed only around 25,000 to 41,000 COVID-19 tests, with the variation due to differences between CDC and community data.

Yet, more importantly, I was privileged.

I was able to get a test, whereas many Americans who are more sick or more deserving than me are told that they do not qualify. My societal position allowed me better medical care than other Americans, which is a feature, not a bug, of a healthcare system that does not treat all Americans equally.

Our failure of testing indicates that we are vastly undercounting the spread of COVID-19 within our borders, and the groups at most risk are also the ones that struggle the most to obtain access to tests. While countries like South Korea tested upwards of 10,000 people a day, the U.S. insisted that the spread would be contained and chose to refuse World Health Organization tests while developing our own.

Beyond testing, privilege permeates the ways we view COVID-19. The privilege of the able-bodied, young and healthy allows some to disregard public health warnings that urge everyone to stay home. Those with high-speed internet at home and enough money to buy a plane ticket have the privilege of not worrying about how they will go to school, while others are given hours to leave campus without a safe place to go. As far as health insurance, 28 million Americans do not have the privilege of considering a hospital visit to be an annoyance, rather than an apocalyptic situation costing money and time. In addition, many lack the privilege of a job that offers sick leave, does not lay you off upon a quarantine order and allows you to work from home. Each of these privileges fundamentally shape the way we individually respond and react to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Here, in Los Angeles, restaurants, bars, gyms and many more public spaces have been ordered to close as urban life grinds to a halt. Food staples are flying off the shelves, and caps on how much milk, meat and other staples can be bought have gone into effect. For millions, these actions disrupt more than a daily routine — more than an inconvenience, they pose an existential threat. For instance, the Federal Reserve Board’s Survey of Consumer Finances found that one in five Americans have less than $400 in savings accounts, and further studies have found that 40% of Americans would struggle to pay a sudden expense of $400.

Collective sacrifice does not mean sacrifice shared equally. Rather, the impact of the crisis is shaped by our existing inequalities and privileges, which allow some Americans to treat quarantine as a holiday while others worry about how they are going to pay the rent in cities that have yet to freeze evictions.

Yet, other families remain fearful of continued U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement raids that threaten to uproot any remaining sense of stability. Families that continue to work in industries vital to the functioning of society but that also have to balance caring for kids no longer in school, families with elderly, immunocompromised or other high-risk members now take risks by just going to the grocery store. Each of these families face structural conditions that shape the way the pandemic affects their lives.

Acknowledging privilege in the time of pandemics means understanding that your choices do not simply affect you — it means advocating for changes that benefit all Americans and not treating a disease with a 2% mortality rate as a funny Instagram caption.

I was lucky to get a test, but that luck was dependent on my privilege to access tests through backdoors that are blocked off to many less privileged Americans. As the crisis continues, we must always remember that though our burden is not shared equally, we each have a responsibility to lighten the burden placed on our neighbors.