Wake Forest hosts event on race in sports

Derrick E. White spoke on the importance of football in the African American community

September 16, 2021

On Thursday, Sept. 9, Wake Forest hosted author Derrick E. White for a conversation entitled “Race, Sports, and the Question of American Democracy.” The event was sponsored by the Wake Forest Department of African American Studies in partnership with Wake Forest Athletics.

Professor of the Humanities and Director of the African American Studies program, Dr. Corey D.B. Walker, led the conversation in which he detailed the history of football at Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), focusing primarily on the career of Jake Gaither.

The lively discussion centered on “Blood, Sweat, and Tears: Jake Gaither, Florida A&M, and the History of Black College Football”, a 2019 book written by Derrick E. White, a professor at the University of Kentucky. Early on in his teaching career, White became an assistant professor of history at Florida Atlantic University. There, he established the sports history program in which students were encouraged to tell stories about sports and their relationship to both American society and culture, focusing primarily on the experiences of minority communities.

White’s students soon began exploring sports at Florida schools like Florida Memorial University and Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University (FAMU). Unfortunately, students looking to uncover important histories were left with little information on the state’s Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs). For years, historians had overlooked the awe-inspiring programs at these institutions. Hoping to remedy this oversight, White decided to research and ultimately publish his own findings on African American history and sports, specifically focusing on the development of football.

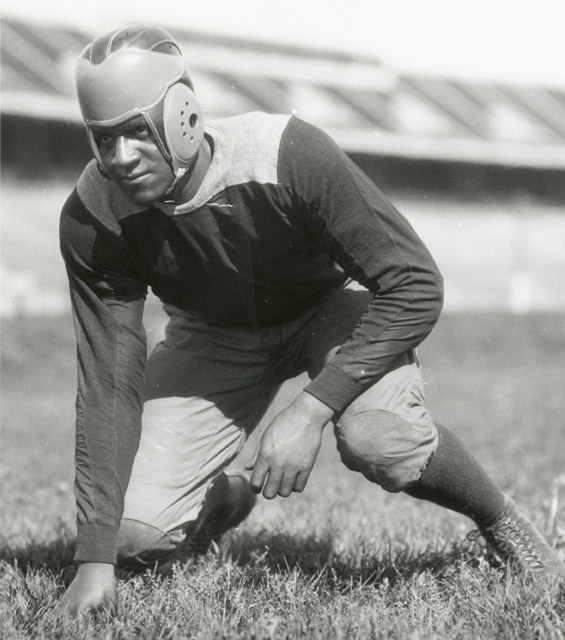

Before football evolved into the sport so many enjoy today, it was confined to predominantly white institutions in the Northeast before eventually spreading down South in the 1880s. Football came of age in the wake of a turbulent period of American history — the Civil War.

Following such a violent era, young men not of age to fight on the battlefield found themselves looking for an outlet to express their frustration. From this sprang football, a game in which men were able to assert their dominance on the gridiron, battling over a “pigskin” rather than with weapons.

Colleges throughout the Northeast began building football programs. However, with serious injuries and even death becoming more common among players, some schools decided to cancel the newly developed sport altogether.

In the African American community, young men were also searching for ways to express themselves during a time in which their rights were rapidly declining. For them, football was a way to assert their masculinity and escape, even if just momentarily, from society’s racial prejudices.

For young Black men, football was not just a sport, but rather a way of creating an educated middle-class in their communities.

While players at predominantly white institutions were issued equipment while those at HBCUs often made their own pads and cleats. In an interesting moment, White described white graduates from Northeastern universities as football “missionaries,” citing their work in spreading the rules and methods of the game. Often, they were scouted and subsequently hired to coach teams at HBCUs. Historians point to the match between Biddle College and Livingstone College on Dec. 27, 1892, as the beginning of football at HBCUs. The game took place on a snowy day in North Carolina and resulted in a win for Biddle.

For historically Black institutions, the church played a substantial role in securing football programs. These schools were often larger and offered post-graduate options for students, leaving more time and funds for leisure and sports in the curriculum.

Prior to World War II, private church universities dominated the football scene with teams like the Tuskegee Golden Tigers leading the charge. Ultimately, the popularity of football led to the creation of the Central Intercollegiate Athletic Association (CIAA) and allowed HBCUs to compete against one another. This association houses 12 universities including Bowie State and Winston-Salem State.

In the second half of the presentation, White spoke about Jake Gaither, a seminal figure in football history. As the son of a minister and a teacher, Gaither was raised in a home devoted to religion and education. Since there was no high school in his town, his parents sent him to Knoxville College where he spent eight years.

At Knoxville, Jake flourished as a compelling debater, but was only considered an average football player. Initially, Gaither wished to become a minister, but upon his father’s sudden death his senior year, he no longer had the funds necessary to attend graduate school.

Instead, he began working at the Henderson Institute teaching social studies and coaching basketball, football and track. In an encounter with famed Vanderbilt, Alabama and Duke coach Walter Wade, Gaither begged to be admitted to a coaching clinic, offering to dress as a janitor just to learn more about the game. Wade denied his request.

In 1937, Gaither was asked to join head coach William Bell at Florida A&M as an assistant. Together, the two worked to develop the growing program in Tallahassee, networking with Black high schools to create a pipeline for talented athletes to join local HBCUs.

Following great success, Bell and Gaither started their own coaching clinic, drawing individuals from across the country keen to learn how to structure their teams more effectively. Despite health issues, Gaither continued coaching for Florida A&M until 1969.

Toward the end of the conversation, Professor White brought up an interesting paradox regarding the integration of sports programs. As more schools throughout the country became integrated, fewer players were seeking spots at HBCUs. Slowly, the system began to crumble; Black principals, administrators and coaches were losing their jobs only to be replaced by white counterparts.

As a result, talented Black athletes were being told to attend historically white institutions, causing HBCUs to lose lots of talent. In other words, as White stated, “integration was necessary, but it came at a cost.”

Derrick White’s discussion of football was both intriguing and timely considering the start of the football season. He helped further solidify the place of football in American culture and placed its roots in a firm historical context.