What freedom is worth

A Chinese international student ruminates on issues back home

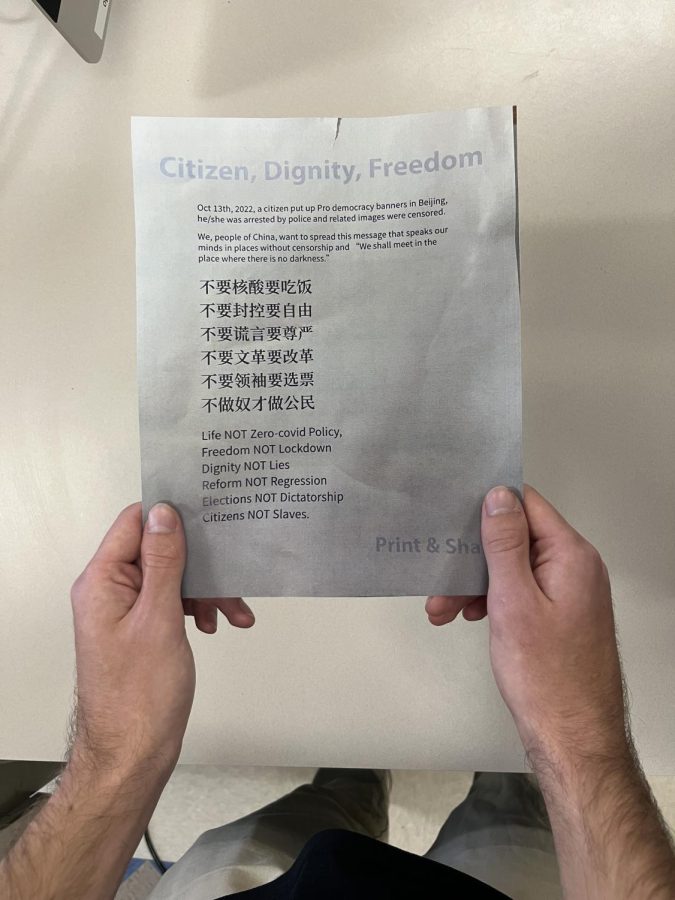

Chinese international students take a great risk when they put up posters like the one pictured above.

November 3, 2022

Editors’ note: Due to the potential risks of writing on this topic, the writer has requested to remain anonymous, and their role in our organization will not be disclosed. The Old Gold & Black respects these requests out of the utmost caution for those who choose to share their stories with us. The events depicted in this account regarding the posters are as they happened in real life; the sections regarding daily routine are amalgamated from the author’s day-to-day life.

She wakes up to the sound of her roommate’s alarm blaring. Her roommate has a 9 a.m. class, and her first class is at 11 a.m. She says to her roommate in Chinese, “Turn off your alarm clock.” Her roommate doesn’t wake up, so she’s forced to get out of the warm, cozy cuddle of her blanket — a blanket that her mom had picked out that went all the way across the Pacific with her.

She turns off her roommate’s alarm for her, and she goes to pick out the outfit of the day. Nothing too dressy— the clothes her mom got for her somehow feel weird amidst the Lululemon and Abercrombie & Fitch that the girls at school; nothing too casual— sweatpants are apparently too casual for the business school, as she was kindly reminded by a graduate student talking loudly behind her back a semester before; and nothing too uptight, of course. She spends ten minutes in front of the mirror and finally comes up with something not too gay, not too straight and not too Asian. She decides to skip breakfast for the day — she could already imagine the disapproving frowns of her parents at the news — but her peers all do it, so her stomach, over time, conforms to the new social norm.

She gets through all of her classes and the group discussions from which she cowers. She dreads small talk; the convo is usually parties, sports and — worst of all — internships, which she dreads. But she gets through them, and soon she is sitting in the warm, comfy chair in the Tribble main room, and her gaze falls upon the black-and-white, A4 poster that is at once vaguely and alarmingly familiar. She almost spilled her drink on it in the urgency to pick it up. When she does, she turns it in her hands like it is a precious jewel that burns.

RELATED: Read more about the posters being put up by Chinese students.

She doesn’t know that this pamphlet could appear in a small town called Winston-Salem in North Carolina, approximately 7,072 miles away from the main character of the pamphlet, doing God-knows-what in God-knows-which ungooglable place in Beijing. She reads the words carefully, over and over again, both the Chinese and their English translation. They slowly became blurry save the six “NOTs” that sharply stung her eyes and the crossed-out image of the figure most frequently seen on TV back home. She shivers inwardly with admiration at the courage and beauty embedded in the simple, succinct Chinese characters and their not-so-acute English translation.

Those words popped up in her story a few days ago. Initially, they appeared on a banner hung from a highway just a block from where her parents lived, but just hours later were erased entirely from the internet’s memory, like a blank and heavy cloud suffocating the minds of those who saw and heard of it but would never mention it again. But not too outside of the firewall, so thousands residing outside the country retweet and repost them. They are hung up on banners in universities all across Europe, North America and East Asia, while the silent mass of onlookers — inside and outside the firewall — speculate and wait with bated breath on the impact of these acts of defiance. Which are what, precisely? She reflects and realizes, with a sinking feeling, that she doesn’t know. Who was the brave individual who had put up the banners? What will happen to him or her? Would the future be revised?

The motherland suffocates and staggers in the chains of unreasonable policies and questionable political actions, failed international contracts and abandoned promises, and all she can do is stare at the pamphlet in her hands, wishing that there was something — anything — that could be done.

Should she go on to print even more pamphlets? Should she write an ode to the fallen brave? Or should she stay silent, just sit there, ponder, and get up and leave? Should she turn a blind eye to those who died, lost their families and lost their jobs due to the covid-policies? Should she pretend not to notice the heavy cloud of something that’s so painfully familiar, billowed over the head of 1.4 billion Chinese people? Should she lash out with the vengeance of a revolutionist and cry for freedom outside of the firewall?

The cold hands and trembling lips would mirror that of those within, though plastered with grimacing smiles and feigned content. She takes out a marker and hesitates. Should she write the national anthem? Yes, that will do.

“Rise, those who refused to be enslaved. Use our blood and bodies to build up the new Great Wall.”

Alas, she has never been to the Great Wall; it has transformed from a wall that fortifies her motherland’s border into a wall that attracts 9.9 million tourists every year, which boosts the economy. A good thing.

Someone approaches her. A fellow Chinese girl. She quickly drops the pen.

“Did you print this?” she asks.

She shakes her head almost too quickly. “It wasn’t me.”

They exchange a quick look between them. “It would be perfect if the formatting looked better.”

She nodded in agreement: it would be better if it were more artistically pleasing.Poetry would be better.

But words are words, poems are poems and freedom is freedom. She can’t really tell which one is worth more, and which one is worth less.