Is ‘once in a generation’ the new normal?

How Winter Storm Elliot and other extreme weather events may be affected by climate change

Research suggests that climate change is contributing to larger and more dangerous storms.

January 9, 2023

As the bustling holiday season ramped up just before Christmas Day, a looming shadow formed over large parts of the United States — the beginning of a once-in-a-generation winter storm. Named Winter Storm Elliott, the major weather event cast surges of arctic air across the country, drastically dropping temperatures to feel like below freezing beginning on Dec. 23, 2022.

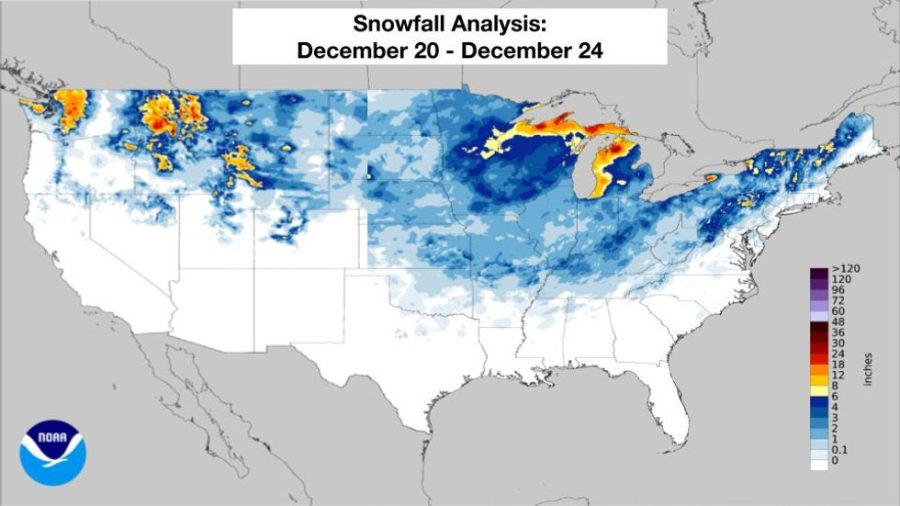

The storm began in the northwest before moving east — reaching the Atlantic border states. According to an NPR report, weather services put in place winter storm warning advisories affecting around 60% of the U.S. population the weekend of Dec. 24. Power outages, heavy snowfall and thousands of canceled flights devastated the country.

The storm became increasingly intense as it traveled east, eventually developing into a “bomb cyclone,” an area of low pressure that rapidly intensifies (or “bombs”) over a short period of time. Based on figures reviewed by The Independent, Winter Storm Elliot caused the death of at least 72 people across the U.S. and Canada. Nearly half of these deaths occurred in Buffalo, NY and nearby areas.

For many places in the U.S., the intensity of Winter Storm Elliott has been deemed a once-in-a-generation occurrence. However, trends in storm severity over recent years may prove storms like Elliott to be more common. As these trends have appeared, many scientists have turned to climate change research to explain the influences driving these weather events.

Dr. Stephen Smith, Ph.D., an Earth Sciences professor at Wake Forest, shared his understanding of the climate science behind the increasing intensity of these natural disasters.

To preface the discussion, Smith noted that weather events are too nuanced to claim that climate change is the cause of any singular event.

“It gets tricky to try to ascribe any individual storm to climate change,” Smith said. “What we’re able to say with respect to the science is more in terms of long-term change.”

As a result, one cannot concretely state that Winter Storm Elliott is a result of climate change. However, with data trends across multiple types of storms and natural disasters, the warming climate may have an impact on how severe this type of weather becomes.

“With hurricanes and tropical storms [that occur] in the summer, they derive their energy from warm water,” Smith said. “So when you get a warming planet, and the average temperature of the ocean is going up by a few degrees, you’re basically increasing the amount of fuel for the storms.”

According to Smith, this does not account for an increase in the frequency of hurricanes. When a hurricane does occur, however, its potential danger increases due to the warming temperatures of the ocean.

Smith remarks that rising temperatures also affect the intensity of winter storms.

“It’s not surprising to scientists that we’re getting more severe winter storms,” Smith said. “It’s actually expected based on the way climate dynamics work…as the climate warms, you get more water vapor in the atmosphere, and when you have more water vapor, you have more precipitation.”

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Agency (NOAA), extreme winter storms often arise as a result of the destabilization of the polar vortex that separates the Arctic and lower latitudes. The polar vortex forms due to large temperature differences between the two regions, keeping the freezing Arctic air largely away from North America. As humans accelerate global warming, temperatures of the Arctic rise faster than other parts of the Earth — a phenomenon known as Arctic amplification.

One theory that continues to be studied by NOAA experts states that the warming of the Arctic due to climate change could cause the temperature differences between the Arctic and the lower latitudes to decrease, destabilizing the polar vortex and weakening the “polar jet stream” that confines Arctic air. This instability causes extreme winter storms like Elliott to occur.

“Winter as a whole may actually get a little bit warmer, but it’s punctuated by more severe winter events because…Arctic air [can] dip down more easily,” Smith explained. “It may be 65 degrees and anomalously warm and sunny one day…and then the next week, you might have this crazy cyclone that dumps a lot of snow and sets record-low temperatures.”

The general question regarding climate change then becomes how these changes will affect humanity and nature. With Winter Storm Elliott, people across the country were face-to-face with the disastrous effects of a severe weather event: chaos, instability and even death. Despite this devastation, humanity is armed with technological capabilities that save countless people from suffering during these natural disasters. Ecosystems, on the other hand, are not as fortunate.

Nature has the persistent ability through adaptation to gradually mold and evolve ecosystems and species. As the environment changes over time, so does species evolution. According to Smith, however, when the climate changes rapidly and unpredictably, these ecosystems are put under duress.

“It’s all stress,” Smith said. “It’s not necessarily that you have this background increase in temperature that’s a stress [on ecosystems], but you also have all of these other things that are happening in the climate as a result.”

He continued: “We’re changing the resting state of the planet [which changes] the interactions that are taking place in the atmosphere, in the oceans and everywhere else.”

As winter storms like Elliott and other natural disasters continue to worsen, human activity may prove to increase the danger against ourselves and the natural world across the globe. What once may have been a once-in-a-lifetime event could become dangerously more common.