Van Jones speaks to challenges, opportunities facing the Class of 2022 in exclusive interview

The CNN host and bestselling author emphasizes the importance of community building

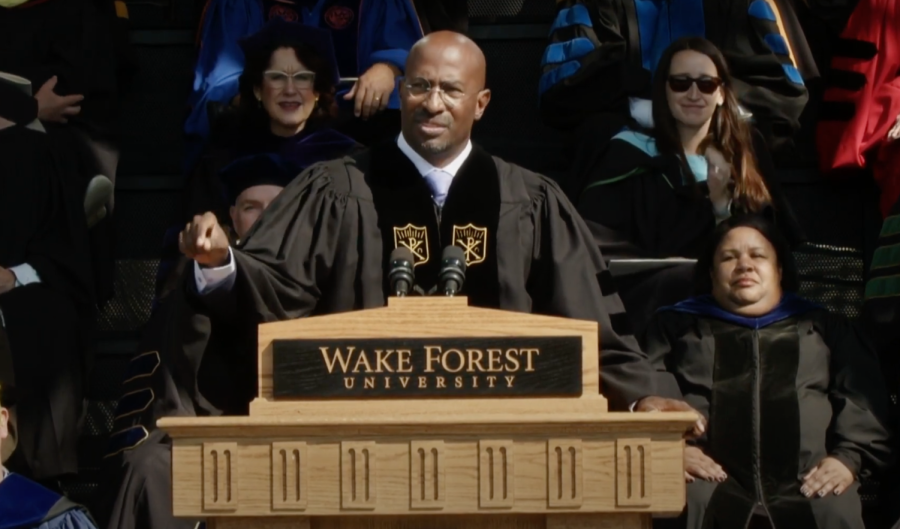

Van Jones delivers his commencement address to the Class of 2022.

May 17, 2022

On Monday morning, the Old Gold & Black sat down with 2022 commencement speaker Van Jones for an exclusive interview. Jones is a CNN host, Emmy award-winning producer and author of three New York Times best-selling books. His advocacy efforts include support of bipartisan legislation such as the 2007 Green Jobs Act and the FIRST STEP Act, during the last four presidential administrations. Jones has also achieved notable accomplishments in his leadership of social organizations such as the REFORM Alliance, the Dream Corps and the Ella Baker Center for Human Rights.

You have given commencement addresses at Morehouse, Vassar, Lane, and Loyola New Orleans within the last five years. You have spoken about the importance of using your community as your springboard, finding common ground to work together, and reducing the ego and expanding the soul. Have those messages changed since you last gave a commencement speech? Have you discovered something else over the past two years?

Yeah, look, I think that it’s harder. You guys are going to have a harder time than a decade ago, or the decade before that and the decade before that just because of the ecological crisis, the political divisions and the technological changes. I think that your own resilience is going to be much more important. The crazy thing is you guys had to learn how to be resilient because you were going to school during COVID-19 and fertilizers fires and everything else. And I’ll be speaking about that a little bit in my speech today.

Aside from changes to our climate and the political division, there is a lot of hatred in the world right now. The past few days have proven that. What is your advice to these graduates today on how to find joy in the world when they’ve been surrounded by this hatred on all levels?

Well, first of all, I’d say put your phone down and look around because most people are pretty good. Most people you actually meet and interact with — even people who vote against you or those who have a different faith or a different background — they’re 95% good. And, unfortunately, cable news — where I work — and these algorithms on your phones amplify the negative. So you tend to be more depressed than you need to be and less competent at finding good allies and good people. And so just recognize that, to some extent, we’re being tricked into thinking that the country is worse than it is. And that the hate is more widespread than it actually is. There is a lot of hate, but there’s also a lot of love and good people out there, too.

You worked at your college newspaper, The Pacer at the University of Tennessee-Martin. How did that influence your career? And how important do you think student journalism is now in the age of heavily politicized coverage?

Almost everything I learned how to do, I learned in college, such as how to take a stand. I also learned how to communicate in a way so that everyday people can be impacted by what I’m saying.

I’m so glad I grew up in a small town in rural West Tennessee and went to a small college. We were writing for working families who didn’t have time to wade through 1000 words to just understand whether their kids were going to have to wear school uniforms next year. It’s hard to get to the point. So I think that journalism is really important. You know, there are two kinds of smart people: the smart people who take very simple things and make them sound very complicated to impress everybody, and the people will take very complicated things and make them sound very simple to empower everybody. And I think that the job of a journalist is to take the complicated and make it simple, which is actually way harder. It’s very easy to take some simple idea and flower it up. It’s hard to take a complex idea and break it down.

Do you think cable news is doing the opposite of what you’ve been taught in college and overamplifying certain things that aren’t that big?

I do think that there’s something missing in the information landscape right now. In cable news, we have to compete against each other for attention, and so that tends to amp up the volume, sometimes at the expense of the nuances. And then the algorithms on our phones are doing the same thing. I think we have more information and less education than we need. In other words, you can find the facts, but what does it all really mean? You know, we have an awful lot of data and a very little amount of wisdom in society.

Now, a lot of the wisdom-bearing institutions —- whether you’re talking about our faith-based communities, labor unions, or even our family structures — have really broken down. And so, you’re not spending a lot of time talking to your grandparents, probably as much as you’re spending time listening and being influenced by whatever TikTok wants you to see. And so that makes it hard, I think, to have a society that is not just well informed, but also well educated with the proper context to make decisions.

How does that change?

I don’t know, I think that’s going to be one of the big challenges for your generation of journalists. Do we need a new social media platform that functions differently? Is there some way to hack Tik Tok and Instagram so that you can make stuff that’s shorter and more visually compelling, but at the same time, more nutritious, for lack of a better term? That’s going to come down to, I think, some information entrepreneurs, more so than just those of us who work in the business who are trying to do a better job. It’s important that this business does a better job. But, we also need better platforms.

You have driven change throughout your life since the very beginning of your career suing police departments in your 20s. How would you advise young people to create beneficial change in the face of governmental leaders and hostile institutions?

Every generation has different tools. Some generations marched in protest. I had my law degree, as a 24-year-old, I had a law degree. So I thought, “Hey, I’m a black kid with a law degree, I’m gonna sue some cops, I gotta do that.” But your generation will have different tools. I mean, you got everything from the metaverse, artificial intelligence and quantum computing. There are so many different ways to make a difference. I think the most important thing is to look in your own knapsack for the tools that make sense to you. Don’t try to mimic what somebody did 10 years ago, 20 years ago or 30 years ago. It’s a different age. As I’ll say today, some of you guys might literally be buried on Mars. We have no idea what you guys are going to do. I think it’s fine to take inspiration from earlier generations, but not instruction. Some of your classmates might wind up being crypto billionaires. I mean, who knows? And so I think the most important thing is to try to use your talent for good. It doesn’t mean you have to go work in a nonprofit organization or take a vow of poverty. It just means whatever skills you have, whatever industry you’re in, look for ways to do good, look for ways to help people, look for ways to make the environment better and look for ways to lift up people who might not have a chance. And if enough people do that, then things tend to work out.

Young people who want to improve the world, but have grown up to see no change are going out to protests about issues of guns and abortion and wonder what good their protests will do. Do you think there’s an issue with apathy for young people today?

Cynicism, resignation, apathy and despair are always with us. It’s always felt hard. The changes that you now take for granted felt very hard. In the 1980s, just trying to get civil unions for same-sex couples was considered very radical. In 2012, President Barack Obama was very afraid to admit that he thought that there should be marriage equality for lesbian couples and for gay couples. That was ten years ago.

Now, you know, it’s all about, you know, genders and pronouns and stuff like that. And so it seems like, well, that issue was easy to win on, but for a couple hundred years, that was the impossible issue. So it’s always hard, and it always takes longer than anything. Nothing ever changes until it does. Whatever the issue that you’re working on is, what I would say is that your source of inspiration and your source of sustainable effort has to come from outside of the cause. Go fishing, spend time with your grandparents while they’re still alive — they won’t always be there, take vacations and keep perspective. And then, from that place of replenishment, you sometimes come back to the cause with a different understanding. And sometimes you realize, “oh, the way we’ve been talking about this has actually been alienating people,” or, “it’s actually it’s not that complicated, just let’s use this metaphor instead of that one.” But actually, from experience, you can really burn yourself out in a serious way if you don’t maintain some balance. It’s a series of marathons for you guys, not a sprint.

So it comes back to what you have said in previous commencements – opening your heart and embracing community?

Now look, I mean, I’m not going to do a bunch of repeats on this commencement speech. I really tried to sit down, and just think about what have I learned.

You know, the magic happens when you reach across lines. You spent part of your life getting deep in a community, deep in a cause, deep in a profession — you have to do that. Otherwise, just it’s just tumbleweed going on all around. Then once you’ve driven that stake in the ground as to who you are and what you believe, then the very next question needs to be: “how can I reach out to people who see it differently? How can I reach out to people look differently, we pray differently, who grew up differently?” Because the energy is in the synergy. The magic is in matchmaking. There are just not enough people who look like you, think like you or pray like you in your profession to make a huge difference. The only way you’re gonna make a huge difference is to work with people who are very different, and who come from different places. And that skill is the fading one in our society where everybody just gets in their corner and screams at each other.

But it’s unbelievable. A very small number of people can make a tremendous difference if they’re representing large numbers of people. So if you’re representing the depression in journalism, yeah, you fail if you’re just one person. There are a lot of people in your profession. Somebody else might be representing agriculture. Somebody else might be representing civil rights. Well, when someone puts all the people together, at first it might seem a little bit weird, but all of the sudden, you start realizing, “well, hold on a second, your kid goes to that school. Oh, there’s a problem over there. Well, why don’t we fix that?” And all of the sudden, something that seemed completely impossible to do can get done in an instant because your network is diverse enough.

I think a lot of times we talk about diversity like it’s a favor you’re doing somebody else. People might say, “let’s be more diverse so that the lesbians can have a place at the table and they can feel better. Let’s be more diverse so that the immigrants can have places and they can feel better.” Diversity is what you do for yourself. It gives you a superpower. It gives you access to the information you wouldn’t have, it gives you insight and a reach that you could never get. It’s really the most selfish thing you can do, to include as many people as possible in your own network. I think we have to start talking about that, otherwise, people feel like they’re supposed to give up their seat at the table for somebody else. No, we’re trying to give you a bigger table.

Watch Van Jones’ full speech here.

Editor’s Note: The above interview has been edited for brevity, clarity and AP Style.