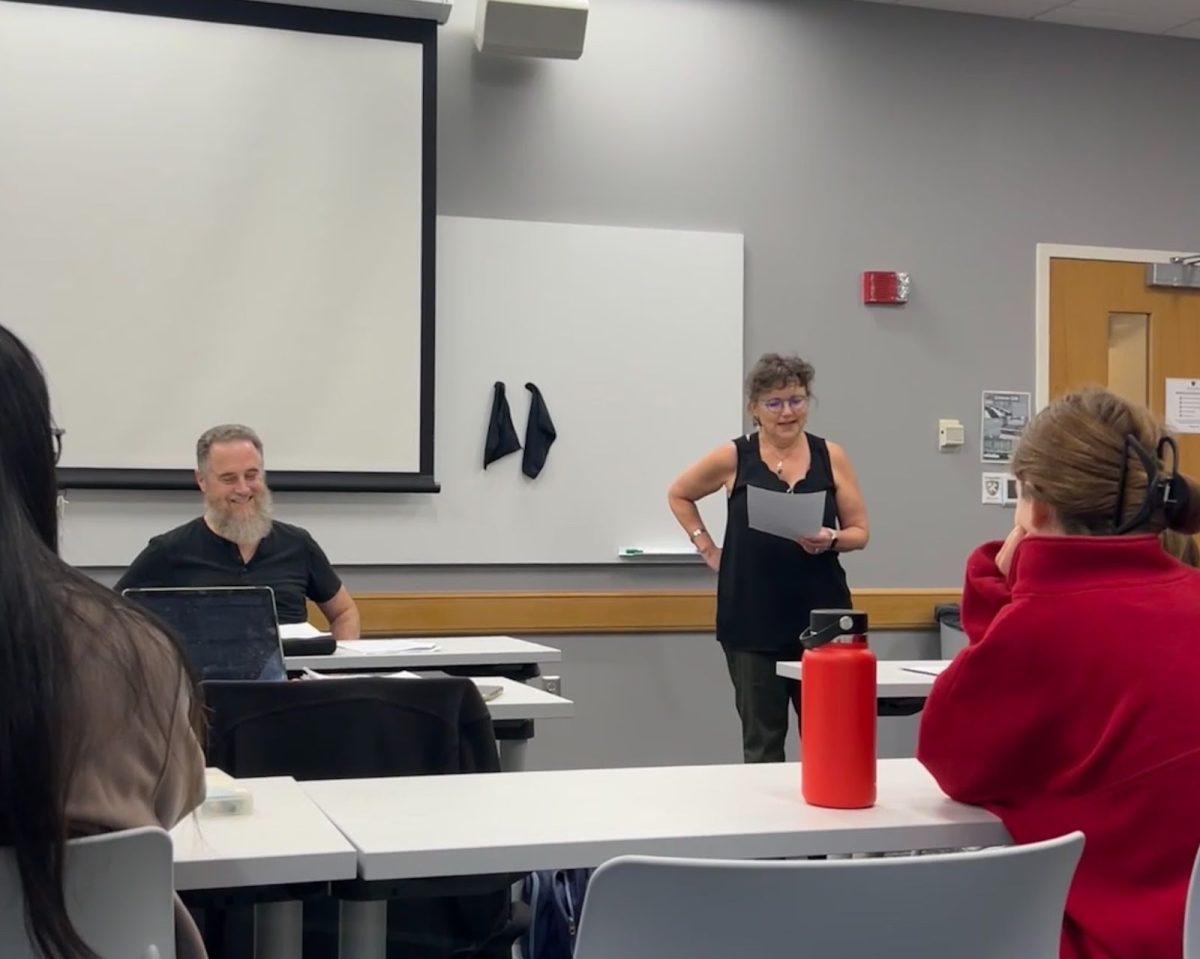

On Oct. 19, The Dean Family Speaker Series welcomed Dr. Christopher Freeburg and Dr. Michael Snediker to the Z. Smith Reynolds Library to discuss “What Aesthetics Matter.” Many students found it difficult to follow along with the talks given by the two professors, prompting discussion about the accessibility of literary events like these.

The two were invited by Dr. Jennifer Greiman, a professor of English at Wake Forest with a special interest in the works of Herman Melville. “[Freeburg and Snediker] are both invested in the ways in which literary aesthetics open up ways of thinking about, for Chris Freeburg, African American studies and African American lives, and for Michael Snediker, queer studies and disability studies,” Greiman said. Through studying aesthetics, both scholars are finding ways to shake loose the predetermined narratives of “death, domination and marginalization” in their fields.

In speaking with Greiman, the work that the two scholars are doing really came alive for me in exciting and illuminating ways. Freeburg and Snediker explore how literature demonstrates the impossibility of understanding another individual’s interiority. This is what Freeburg terms “epistemic estrangement,” and he uses Melville’s short story “Benito Cereno” to fully tease this out. Greiman said that, for Snediker, “Melville is actively using language to unsettle the character form — to push back against the idea that persons are what we think they are.”

Unfortunately, I found it difficult to piece all of this together during the event, and from my conversations with peers afterward, it seemed this was a rather common sentiment. From what I gathered, most were able to pick up on some of Freeburg’s main arguments, but Snediker was almost entirely indecipherable.

While I am no stranger to incompetence and confusion, I think that the event inherently lends itself to a high degree of difficulty, given that it is a verbal presentation of highly academic, highly dense writings that are deeply entrenched in specific scholarly fields.

I wanted to speak to Greiman to determine where this obfuscation comes from and whether or not it is necessary.

“Literary scholars,” she said, “are often held to an accessibility standard that physicists or mathematicians aren’t… but literature is about communication, and so there is an expectation that it will be transparent, but sometimes we are doing really technical things.”

While acknowledging that Freeburg and Snediker, for example, are deliberately working with difficult subject matter, Greiman also argues that there are ways for students to find value in them.

“What I want to do with my English majors is get them to the point where, even if they don’t understand every move of an argument, they can at least understand why an argument is being made and what the stakes are,” Greiman said.

I find myself sifting through deeply ambivalent, mixed feelings about this issue. On the one hand, I am reverent to the seemingly infinite potential of language and the great reward that accompanies learning material that was once thought ungraspable. On the other hand, I want to see literary studies thriving, and I want to see events like these attract students without the incentive of extra credit.

Indeed it is my biggest fear, as an English major, that the terminus of this field is a self-imposed muteness or illegibility, in which our unique passion for literature becomes the very thing that keeps us from sharing it with others.

As Greiman and I were wrapping up our conversation, I think we began to approach a solution. When I asked her what might be lost in converting academic language into a more colloquial form, she said that we do not have to look at it that way. Instead, there is a way in which casual and academic language can support each other.

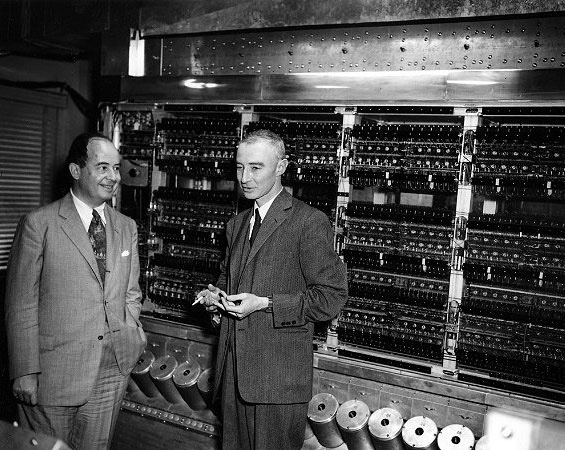

In mathematics, for example, we think of even numbers simultaneously as {2,4,6,8…∞} and as “all numbers of the form 2k for some k in the set of all integers.” Both of these definitions have their pros and cons, but when we use the former to better understand the latter, a perfect conception of even numbers arises. There is a lot of potential in the interplay between abstract, rigorous concepts and their more lucid examples or shorthands.

As Greiman said, “In conversation, you can think through a concrete example and then go backward and funnel that back into the more difficult reading.”

Like training wheels on a bike, examples and anecdotes play a vital role in our mastering of difficult concepts. What I think events like the Dean Family Speaker Series could greatly benefit from moving forward, then, are more training wheels.