Oval Offense: If Biden fails to make his mark, will anyone succeed?

Despite being handed a great deal of crises, Biden is unlikely to join the ranks of presidents such as F.D.R. and Lincoln

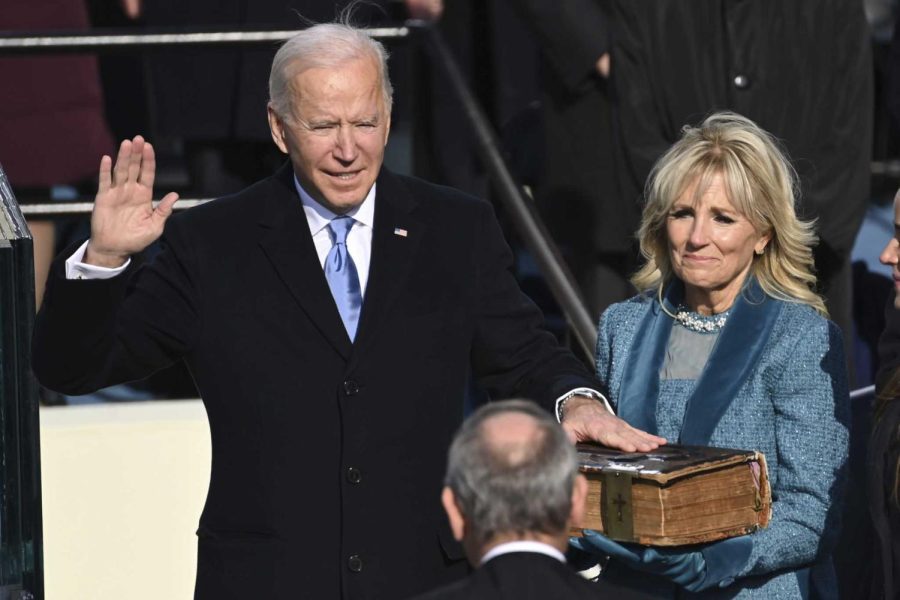

Courtesy of the Houston Chronicle

Joe Biden is sworn in as the 46th President of the United States.

January 20, 2022

Crisis is indispensable to the American presidency. Little else provides such an open pathway to obtaining political power and ensuring a historical legacy. It was the great regret of Bill Clinton that no such great crisis occurred during his presidency and that he was in essence denied the opportunity of enshrining himself among the likes of Abraham Lincoln and Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Today the likes of Lincoln and F.D.R. stand in a political majesty built on the accomplishments in the nation’s most perilous times. A third contender, George Washington, lies in a similar position, defined and deified by his wartime accomplishments — though they pre-date his presidency. Seemingly, the common factor among these men lay in their respective abilities to adequately deal with crises that struck the very heart of the country: three wars and a catastrophic economic depression. So it appears to the newly-inaugurated president hoping to leave their respective mark, that there is — ironically — nothing that one might wish for more than a good, honest disaster to take care of.

Since he was sworn into office, President Joe Biden has inherited a plethora of disasters. Among these is a pandemic that has surpassed the death toll of the Spanish flu — and the combined total American deaths in both world wars — and sent the country into a spiral. He inherited the office from an administration that actively attempted to challenge the legitimacy of the government and was left to pick up the pieces of a deeply rattled capital city in the wake of the mass mobilization against his electoral victory. The world’s leading climate scientists predict an impending climate emergency — one which was already proving to be difficult to address before the pandemic. Abroad, Biden has taken to the task of withdrawing from Afghanistan — and now of navigating the tension on the Russo-Ukrainian border — all while attempting to find a new balance of power in American dealings with the People’s Republic of China. Such disasters may fall short of the Second World War or the American Civil War, but they should portend the opening route for another sanctified American president to join the ranks of F.D.R., Washington and Lincoln.

But this has clearly not happened. At the moment, Biden faces an ever-diminishing approval rating — he is trapped in the low 40s at a time when presidents typically enjoy the height of their popular support. His attempts at deal-brokering in Congress have been barely better than mixed; he does not enjoy a firm grip over his own party and he has certainly found little success in any attempts to bring oppositional figures into his own camp. His party faces dire odds in the 2022 midterm elections and it would appear that his prospects for decisively addressing each crisis grow worse by the day.

Without a doubt, the great American presidential forebearers of disaster management faced equal domestic hostility, if not greater. F.D.R.’s Congress actively threatened to impeach him and Lincoln had to go as far as to suspend habeas corpus for war dissenters. But they faced such hostility with as many followers as they had enemies, and Biden seems to have enjoyed no such luxury.

But why? Biden is no Lincoln. Nor was F.D.R. Yet given the great scale of disasters which have befallen him, it seems surprising that Biden has proven to be one of the presidents with the most enemies and the least number of friends. Is it because of a denial that the scope of these disasters is anywhere near as great as what F.D.R. and Lincoln faced? Perhaps. But apparently, a great body of the American population recognizes the immense scale of these crises while simultaneously viewing Biden as a poor president and opposing his agenda. Is it related to his legislative attempts then? Perhaps. But the withdrawal from Afghanistan was wildly popular before he did it — so perhaps it was his failure to extract the American troops without casualties. He was ridiculed for the drone strikes which took the lives of civilians during the withdrawal — and yet, despite popular support for the resulting abandonment of drone strikes — no one seems to care.

Biden has certainly not flawlessly addressed the pandemic issue — nor any others — but no American president has ever conducted their administration flawlessly. However, it is quite curious that even in his victories, the attention has instead been put on his many failures above his successes. Perhaps it is that he inspires little of the same following enjoyed by his predecessors. It must be more than just that.

Whether it is mass media, increased political mobilization or simply a plain new political consciousness in the American people — the time of the president as a national hero has ended. One should be sure to not overstep in analyzing the past with the lens of today. To say that the most highly regarded presidents did not face sizable criticism and attack for their administrations in their time is a fallacy. But it is also true that in spite of that backlash, they maintained networks of vertical power, held the strength to dictate the mechanisms of party and state and in large part, the political agenda and directed forward those who worked beneath them. It seems unlikely that today, or in the future, the likes of such presidents with their power and enduring historical favor will be seen again.